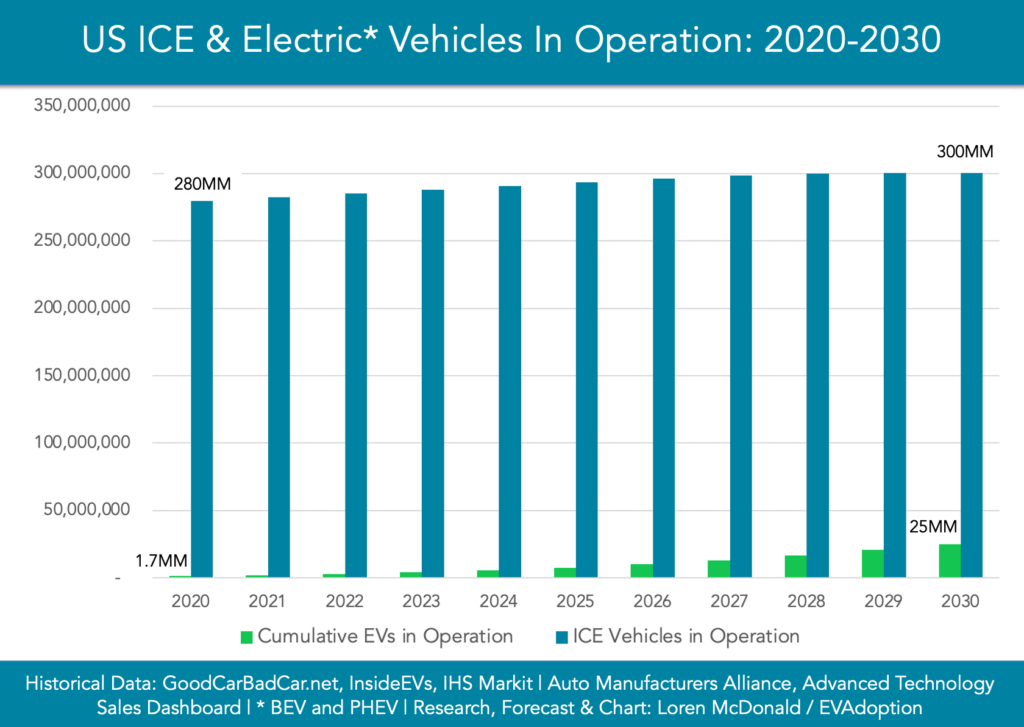

US sales of electric vehicles are expected to increase significantly this decade, however, by the end of 2030 EVs will still comprise only a tiny percentage of vehicles in operation (VIO) and the number of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICE) will actually increase by 20 million. These are the findings of new EVAdoption analysis.

To complete the analysis required identifying or forecasting several data points and models, including:

- Forecasting EV (BEV and PHEV) sales out to 2030.

- Calculating the total number of EVs in operation, including modeling the percent of EVs that would go out of operation each year.

- Researching historical and forecasting the future number of total vehicle sales, the number of vehicles in operation, and number that go out of operation each year.

- And then bringing it all together in a model of the total number of ICE and electric vehicles in operation by the end of 2030.

Following are the step-by-step inputs and data:

2030 EV Sales and Share of New Vehicle Sales

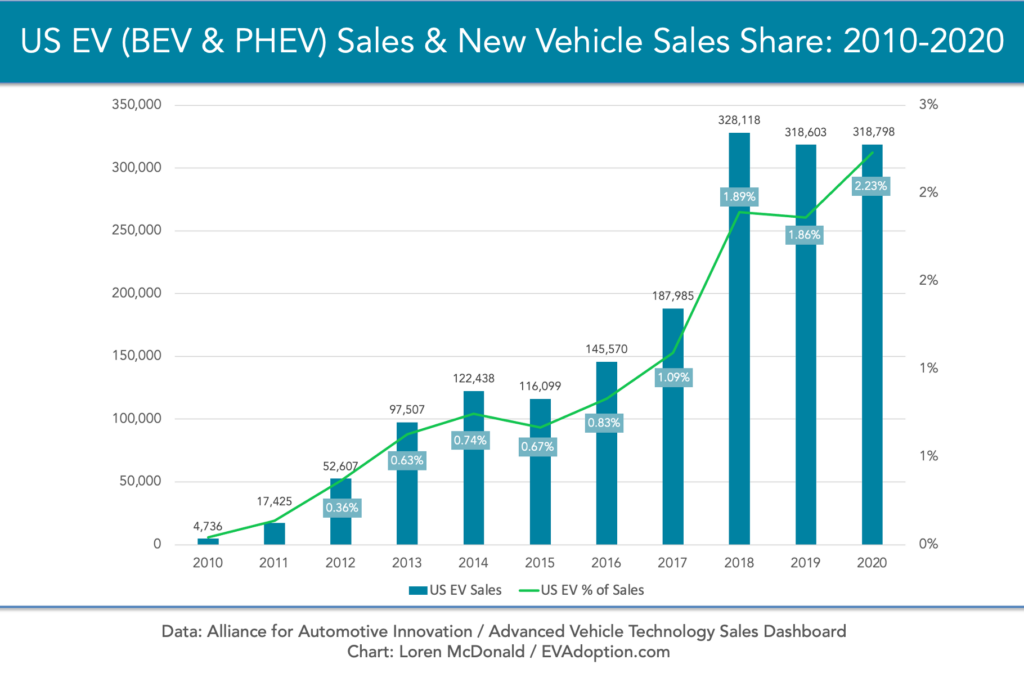

After 11 years (starting in 2010) of the modern/contemporary EV period, combined US sales of EVs (BEV and PHEV) reached 318,798 in 2020. Sales, especially early in 2020, were greatly affected by the Coronavirus stay at home orders and people losing their jobs. As a result, sales were flat compared to 2019, but EVs increased their share of new vehicle sales slightly to 2.2% because overall sales of new ICE vehicles declined significantly. Sales of EVs have basically been flat the last three years and have hovered at +/- the 2% of total light passenger vehicle sales.

While the future powertrain of light passenger vehicles is clearly electric, we have a very long way to go and many hurdles to reach 100 percent of new vehicle sales being electric (either just BEV or BEV and PHEV). So far in 2021 we’ve seen chip shortages, battery recalls, factory and production delays, supply chain issues, and more get in the way of the supply of EVs for the US market. Not to mention OEMs continuing to prioritize their available EV production for Europe due to the EU emissions mandate and higher demand.

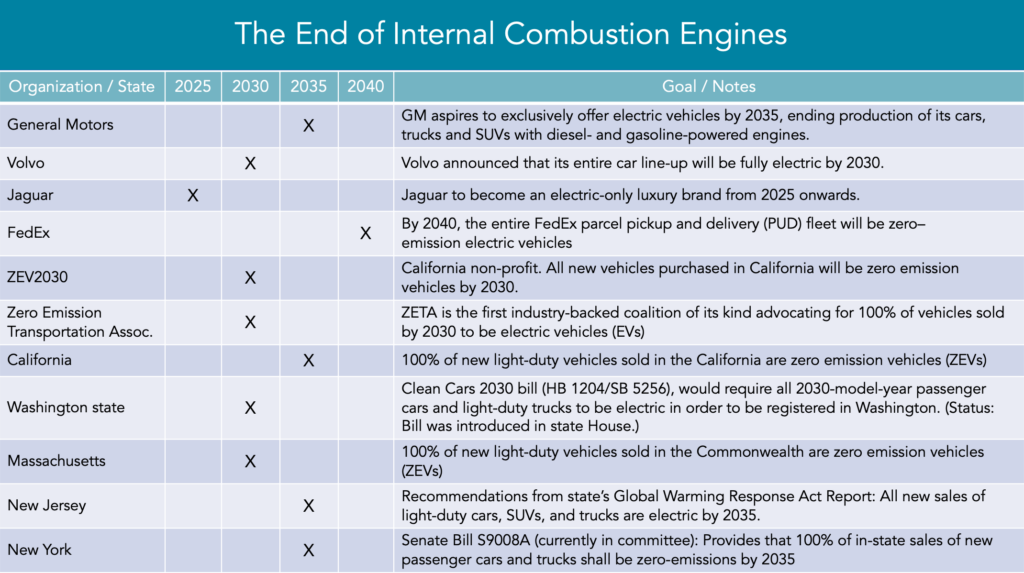

And while many of the legacy automakers – along with several states – have announced plans or “aspirations” to end production of ICE vehicles or ban their sale completely, the reality is we may not see a federal ban of ICE sales ever – or perhaps not before 2040.

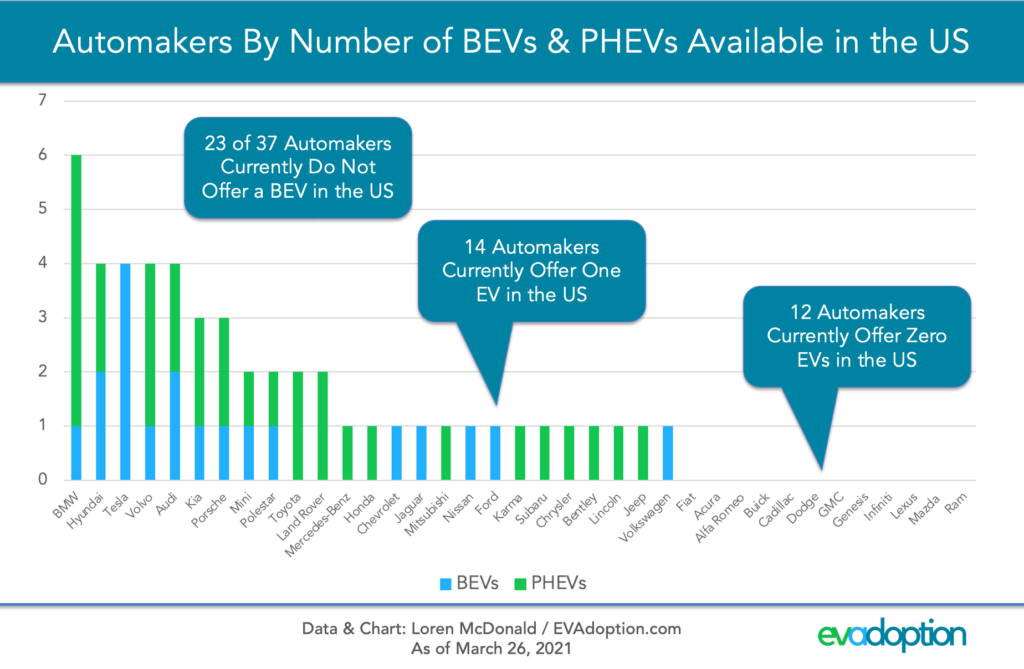

Despite big plans and promises by many automakers, today 27 of 37 major automakers do not offer a single BEV for sale in the US. And 26 automakers offer either zero or only one EV (BEV or PHEV) for sale in the US.

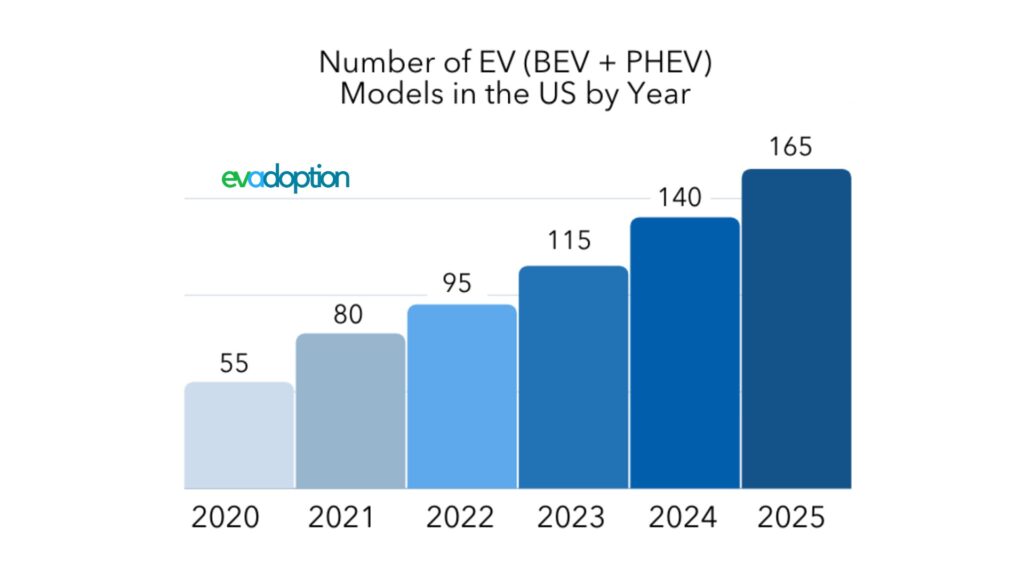

On the positive side, however, there are many new and compelling EVs that will be available in the coming years. In fact, we should see a doubling of the number of available models from 2021 to 2025.

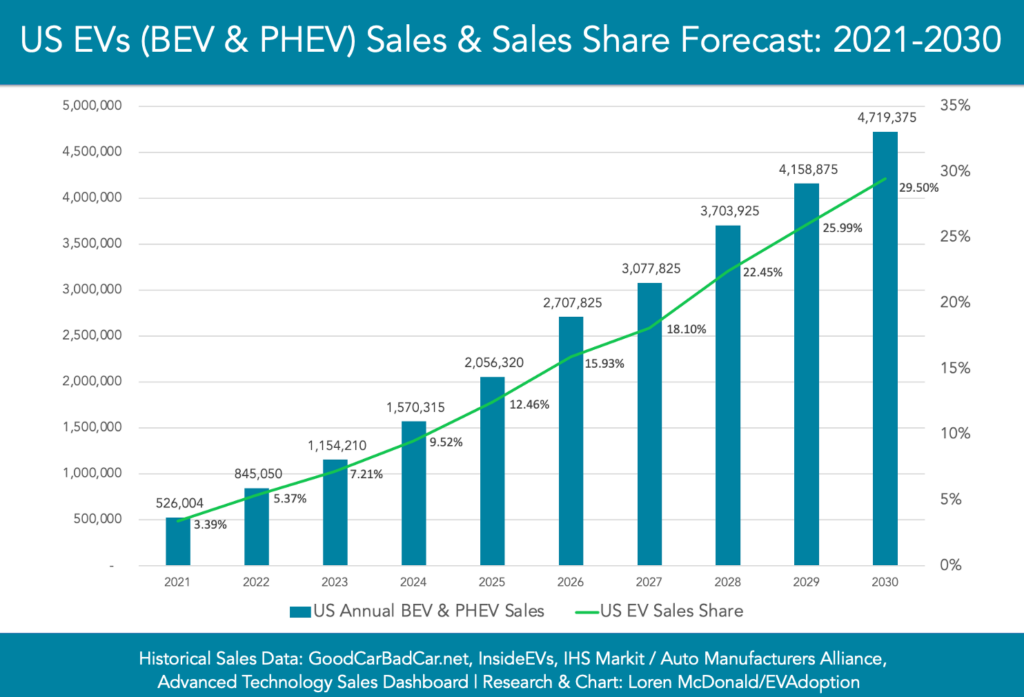

In my latest sales forecast for combined sales of BEVs and PHEVs in the US, I have sales climbing to 4.7 million in 2030 for an estimated sales share of 29.5%. There are, however, literally dozens of variables involved that could see the actual sales share reach perhaps as high as 40%-50% or only the low 20s. But I believe the near ~30% share is quite realistic based on my forecast of sales volume for ~240 EV models that will be available by the end of 2030.

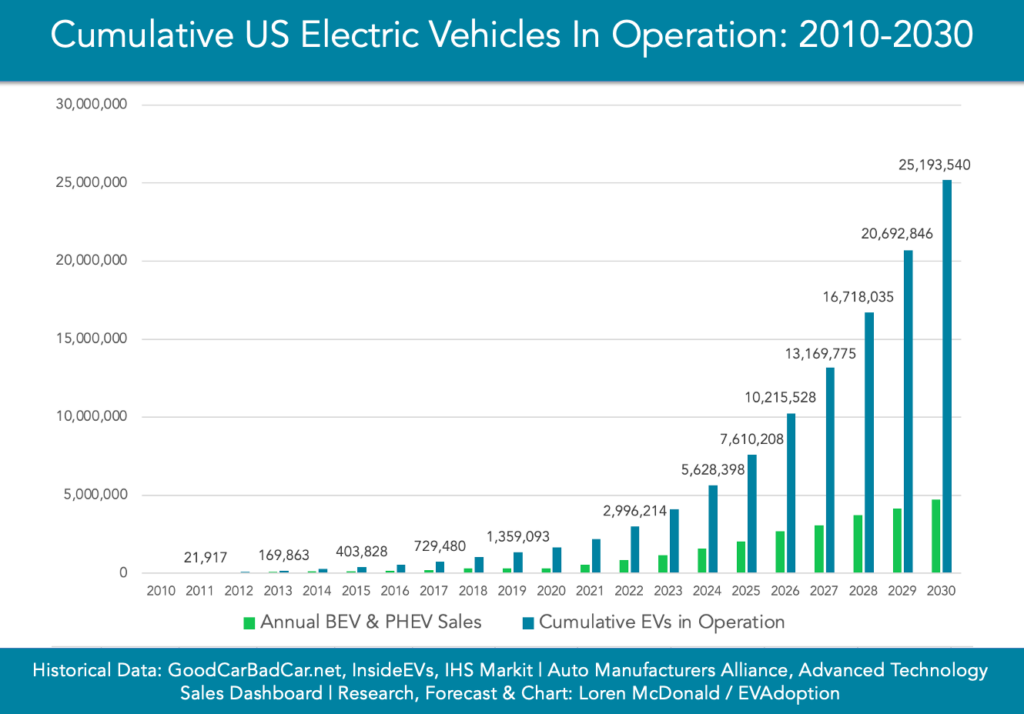

Adding up the annual sales beginning from 2010 gets us to approximately 26.2 million cumulative electric vehicles sold, but factoring in an increasing rate of EVs going out of operation each year, we arrive at ~25.19 million EVs in operation. This is an increase of 14X from the roughly 1.8 million at the end of 2020.

How Many Vehicles Go In and Out of Operation?

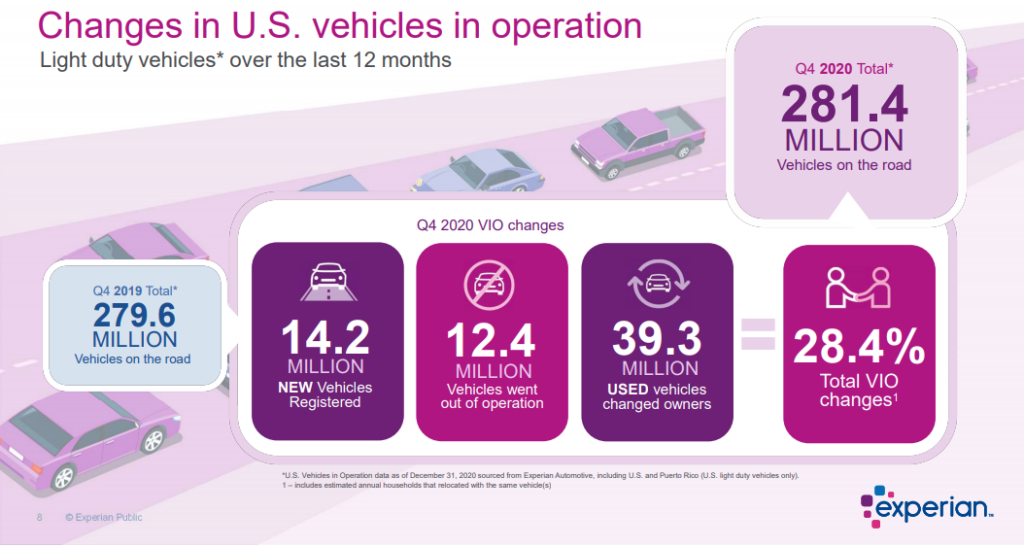

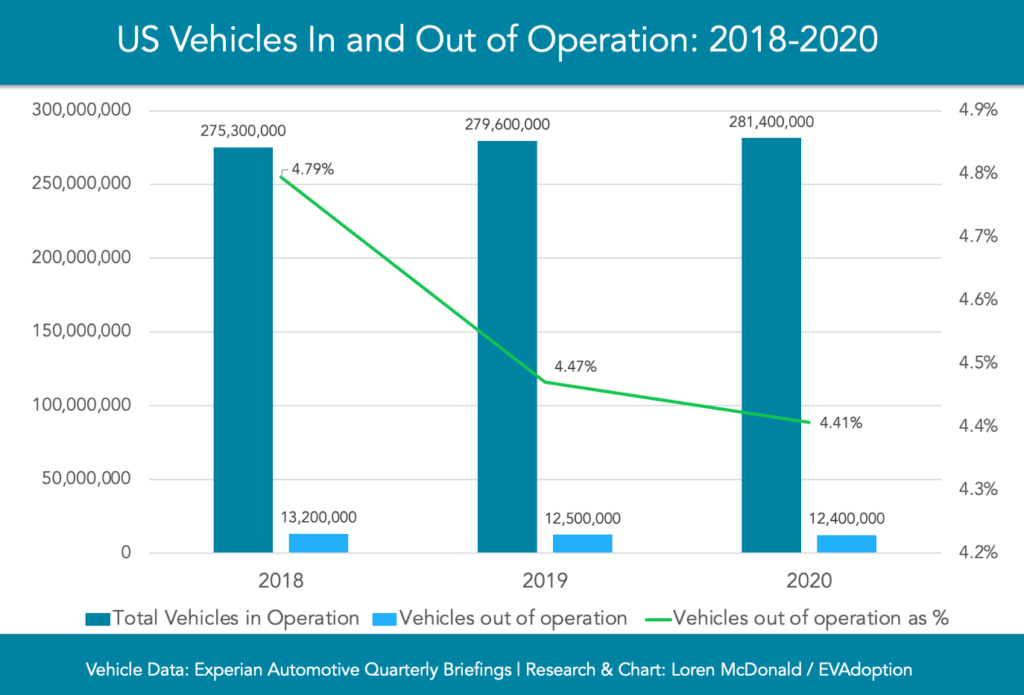

How many vehicles go out of operation each year in the US? According to the Experian Automotive Quarterly Briefings, over the last 3 years the number of vehicles going out of operation has actually declined to 12.4 million in 2020 from 13.2 million in 2018. On a percentage of total vehicles in operation, the number of out of operation vehicles has also declined to 4.41% from 4.79%.

This trend is likely due to several factors including that cars are simply lasting longer than they used to, people are holding on to them longer, used car sales continues to increase, newer cars are costing more and are less affordable, and of course in 2020 we had the impact of the Coronavirus and job losses likely also leading to households holding on to cars longer. And if a decent percent of white collar workers continue to work from home at least a few days per week, many of them may decide to hold on to their car longer because of fewer days commuting and lower overall miles travelled each year.

In the past few years the net increase in vehicles in operation has declined (chart below), mostly due to a decline in new vehicle sales. I expect, however, the increase in VIO for 2021 to return to above 1% and 3+ million net additional vehicles.

Part of what will continue to feed an increase in the overall number of vehicles in operation is longevity. The average age of vehicles in operation has increased 40.5% since 1995 from 8.4 years to 11.8 years in 2019. With gas-powered cars and trucks accounting for a majority of new vehicles being purchased likely until around 2032-2035, it means that a high percentage of gas-powered vehicles purchased in 2021 will still be on the road in 2033.

Now as my friend and EV journalist extraordinaire John Voelcker pointed out to me, new cars tend to be driven many more miles per year than older ones – especially in multi-vehicle households. And when you combine that with newer cars becoming increasingly more fuel efficient, without building the model, it is possible that the 20 million more and 300 million in total gas-powered VIO in 2030 might actually pollute less and release fewer carbon emissions than the 280 million in operation at the end of 2020.

Combining all of these factors and data points produces what the likely number of total vehicles will be in operation in 2030 and broken down by EV and ICE vehicles. And the result isn’t pretty for electric vehicle advocates and policymakers.

As impressive as the EV sales growth reaching ~30% of new vehicle sales is, the percentage of cumulative electric vehicles in operation in 2030 would still be tiny and a drop in the bucket at approximately 8%. Said another way, in 2030 only 8 out of 100 vehicles in operation will be electric.

What Does This Mean for Transportation Policy Decisions?

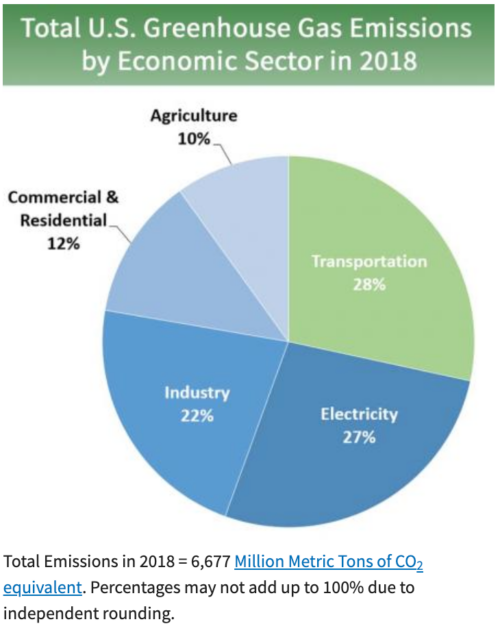

The need to transition off of gas- and diesel-powered fuels is clear if we want to reduce pollution, carbon omissions, and lessen the impact of cars on climate change. In the US transportation is estimated to account for 28% of greenhouse gas emissions, more than any other sector.

Even if the transition to 100% new vehicles being electric (or hydrogen powered) happens more quickly than my forecast, it will likely still take another 30 years to reach 98% of vehicles in operation not being powered for the internal combustion engine. In a forecast from 2020, I pegged that it would likely take until 2052-2058 to reach 98% of all vehicles in operation being electric.

Increasing the adoption and sale of electric vehicles more quickly can get us to 98%-100% non-gas-powered vehicles sooner, but math tells us that getting rid of 300 million gas vehicles that last 12 years or more is a huge burden that can’t be sped up naturally.

Increased investment in incentives (something I don’t believe actually has significant impact on sales), building out EV charging infrastructure, instituting emissions mandates (like the EU), and outright bans of ICE vehicles as is proposed or law in several states, are all important elements in the transition away from fossil fuel powered vehicles.

But my analysis reveals if we really want to speed up the transition to or near 100% electric vehicles in operation we actually must have a greater focus on removing inefficient, polluting, greenhouse gas emitting fossil-fuel powered vehicles.

There is no simple solution to this monumental challenge of removing 300 million vehicles from our roads. Almost any approach to taking existing gas and older less efficient vehicles out of operation is going to be highly unpopular with many Americans, extremely costly, and put a higher-level of burden on lower- and middle- income households that often can only afford older used vehicles.

With that said here are a few ideas to get the conversation going about how to speed up the transition:

- Put teeth into the gas guzzler tax and have it apply to SUVs, crossovers, pickups, and vans as I outlined in this article from 2019: Trucks, SUVs and CUVs Inclusion in the Gas Guzzler Tax Is 20 Years Overdue. All new non-commercial vehicles that are below a certain MPG or other efficiency standard should have a significant tax that increases for each MPG below the threshold.

- Institute a “trade-in and cash for guzzlers “program that would provide an instant rebate to owners of specified older in-efficient gas models that would be applied towards the purchase or lease of a new or used zero- or low-emissions vehicle.

- Establish community college and technical training programs especially in disadvantaged communities for the conversion of older gas-powered vehicles into either plug-in hybrid or fully battery electric vehicles.

- Provide incentives that actually discourage the driving and need for 4-wheeled vehicles and build out first- and last-mile micro-transit solutions that enable easier use of public transportation and other mobility options for households in suburbs and other locations without convenient access to mass transit. These programs should encourage many people to move to become either zero or one-vehicle households.

- Instead of the current federal EV tax credit, reformulate it based on exchanging older gas- or diesel-powered less efficient vehicles and toward the purchase or lease of a new or used electric or hybrid vehicle. A huge problem with the current EV tax credit is that not only are the credits going mostly to upper income households that don’t really need it to buy or lease an EV, most are probably replacing either another EV, a hybrid, or better than average fuel-efficient vehicle. For example, in 2018 Tesla revealed that the top 5 most traded in vehicles were the Honda Accord, Honda Civic, Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf, and BMW 3 Series. The Accord and Civic are two of the most efficient ICE vehicles on the market, the Prius is a 50 MPG hybrid, and the LEAF an electric car. Even the BMW 3 Series gets up to 26 city / 36 highway miles per gallon. The tax credit (or rebate) needs to be designed and weighted to incentivize people to replace older gas guzzling, pollution spouting vehicles with low- or zero-emission vehicles. A risk of course is that the price of used and new fuel efficient vehicles might increase, reducing the net affective value of the trade-in dollars.

What else? Let me know in the comments what type of programs could more quickly remove older gas guzzlers from our roads?

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

10 Responses

Hello Mr. McDonald,

why did you revise your 2021 EV sales forecast downward from 585,375 units?

https://evadoption.com/forecast-2021-us-ev-sales-to-increase-70-year-over-year-cleantechnica/

Best Regards

Stephan, thanks for noticing and asking. There are several reasons I reduced my 2021 forecast:

– The chip shortage specifically the overall continued supply chain issues for autos and BEVs in particular.

– The delays on the Ford Escape PHEV – for which I had forecasted pretty significant sales.

– Toyota RAV4 Prime low supply – there is HUGE demand for the RAV4 Prime, but Toyota is prioritizing production for China and Europe, so the US gets very few.

– Delays with the Lucid Air and Rivian vehicles

– Hyundai Kona battery recall which is essence takes 80,000 batteries that would have gone to Hyundai BEVs out of circulation.

– And Tesla’s Q1 sales in the US (based on registration numbers) did not look good, with the Model 3 falling off a cliff and the Model Y declining in Feb and March. March (last month of the quarter) is usually a strong month for Tesla, so this portends that perhaps competition is starting to have an impact combined with Tesla’s early adopter customer base may be dwindling.

I expect to do a deep dive again in the next few months and update the 2021 forecast again.

thanks for the detailed explanation, just one remark from me

How do you know that the battery recall by Hyundai will negatively affect BEV production? It may affect sales due to a reputation hit, but I don’t think that there is proof that it will limit BEV production. Hyundai just decided to increase its Ioniq 5 production target in 2021 from 70 K to 90 K units.

“Given the overwhelming demand for the Ioniq 5 in South Korea and Europe, it was reported in the Korean press that Hyundai had decided to increase the EV’s global production target for this year from 70,000 units to 90,000 units. A report from edaily.co.kr dated March 8 said Hyundai was yet to discuss the increase in targeted production with the labor union. Production of 70,000 units requires overtime work for about four days every month.

The significant increase in production would require more overtime work, not to mention a steady stream of component supplies. An insider has said that Hyundai has enough battery supply to meet the higher annual production target of 90,000 units.”

https://topelectricsuv.com/news/hyundai/hyundai-ioniq-5-details-pre-orders/

Stephan, well I don’t have inside info at Hyundai, but I’ll check out the links and information that you shared. That said, I’m just saying that global battery supply is limited. Hyundai, Kia, Toyota, and many more OEMs are bringing a very low volume of BEVs and PHEVs to the US because there is greater demand in China and the EU (because of the emissions mandate). These OEMs can only produce so many EVs because they don’t have enough supply of batteries. Hyundai has to take 70,000 battery packs that would/could go to net new EVs – but instead use them to replace the Kona recalled batteries. Perhaps Hyundai is significantly increasing the number of batteries from its supplier(s) – but they are still starting at a net -70,000.

The ambitious goals for Carbon emissions will be possible only when old gas guzzling polluting vehicles pre 2018 are phased out and replaced with BEV. The cost benefit analysis will weigh in EV favour but financing the new acquisition should be less burdensome and fairly easy.

Otherwise if you leave it to new purchases, the desired results may not be visible.

With additional charging stations and better spread, the range anxiety is obviated. There should be better incentives to switch to EV.

Hi Loren, above you mentioned that you “expect to do a deep dive again in the next few months and update the 2021 forecast again.” Have you had a chance to update this article? Very interested in how the market developments over the last 8 months may have impacted your forecasts. Thanks

I haven’t updated things yet – will be in the next few weeks. But my current estimate for 2021 is ~640,000 and 1.11 million for 2022. All subject to change.

Why isn’t the cost to the environment of mining and producing batteries being taken into consideration? Where do these batteries come from and in what countries is the mining taking place? What does the future of mining and batteries look like?

Saw you great article today, four days short of a year ago, May 8th. My interest is that i have begun converting pre-2005 passenger cars and light-duty trucks to electric. This segment of EV’s seems as if it is deliberately neglected, though it makes the greatest sense when all is considered of the future in this industry. Could there be some sort of study on this specific market of the auto electrification business?