On February 5, Mike Thompson, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures announced the introduction of the Growing Renewable Energy and Efficiency Now (GREEN) Act (PDF). For electric vehicle observers, the legislation contains two key provisions: The first would extend the tax credit to automakers who already reached the current phaseout level of 200,000 EVs sold with another 400,000 vehicles, but with a reduction to $7,000 from the current maximum $7,500 credit.

The second key EV provision creates a new refundable credit for buyers of used plug-in electric cars from date of enactment through 2026. Buyers can claim a base credit of $1,250 for the purchase of qualifying used EVs, with additional incentives for battery capacity. The credit is capped at the lesser of $2,500 credit or 30% of the sale price.

I’m personally not a fan of the Qualified Plug-In Electric Drive Motor Vehicles (IRC 30D) – commonly referred to as the “Federal EV tax credit” – as I believe it has been an abysmal failure. Rather than reforming the tax credit, it’s time to admit it hasn’t worked and blow it up and move in a different direction.

This is not meant to denigrate the hard work that many very smart and wonderful people put in to get the tax credit finalized back in 2009. The tax credit was well intentioned, but it ultimately was a very flawed compromise that has actually done very little to move the EV adoption needle in the US since 2010.

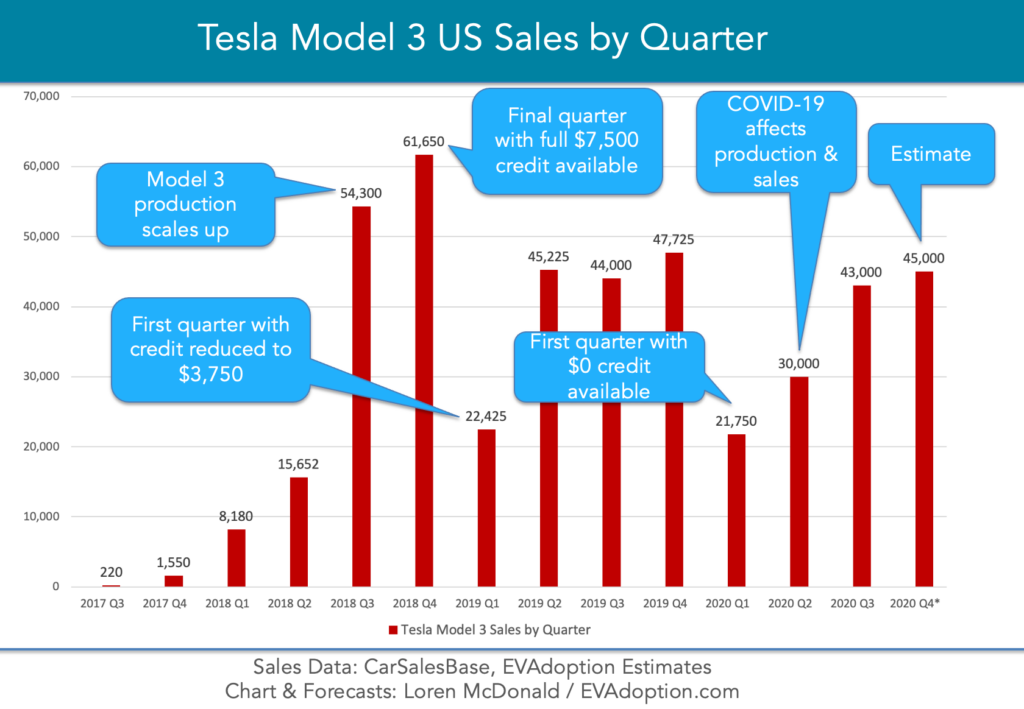

During the 11 years that the federal EV tax credit has existed, electric vehicle sales have not amounted to a hill of beans. It took 9 years for EV sales to surpass 200,000 in annual sales, reaching 325,000 in 2018. But that jump had little to nothing to do with the tax credit, but was a result of Tesla scaling up production and sales of its popular Model 3. In fact, without the Model 3 sales numbers, the US would still be hovering in the low 1% range for EV sales share.

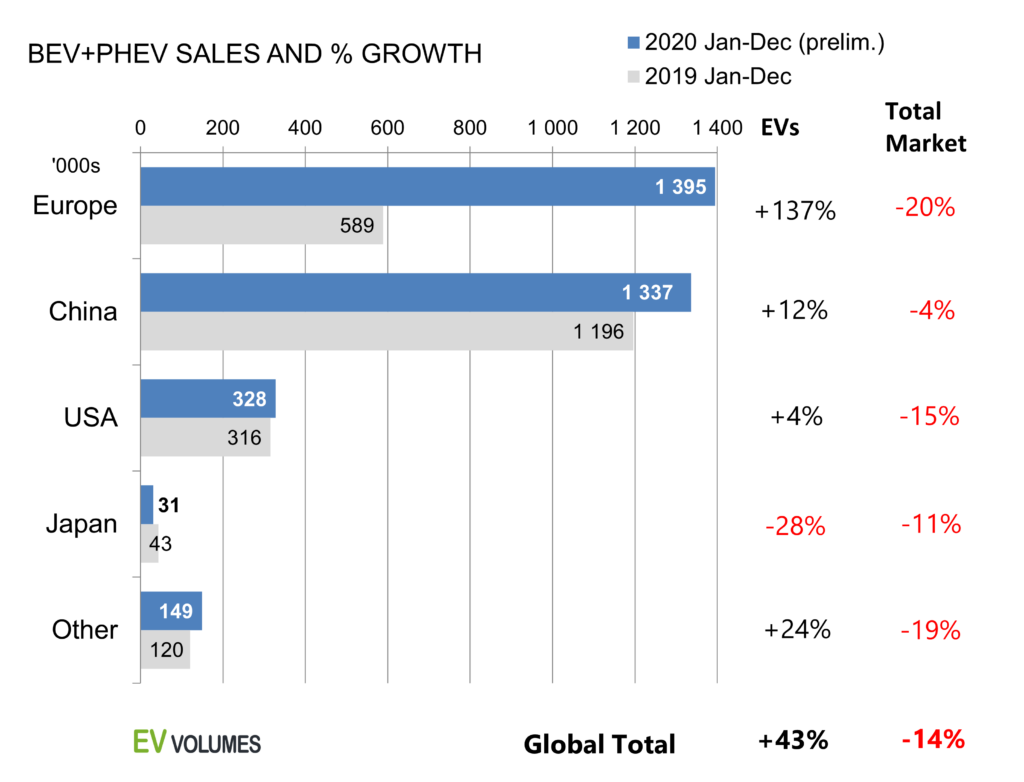

We have seen proof of an approach that can actually drive significant EV sales and that is the European Union’s Emissions Mandate which led to 3X-4X increase in EV sales share across many EU countries in 2020 versus 2019. The overall EU EV (BEV and PHEV) sales share ended up around 10 percent, versus the 3 percent for 2019.

And in the chart below from EV Volumes you can see that even despite the Coronavirus pandemic in 2020, sales of EVs in the EU increased 137% in 2020 over 2019, versus only 4% in the US.

Modification of Limitations on the Existing EV Tax Credit

If the US is serious about dramatically boosting sales of EVs, a consumer tax credit is not the answer. However, if the credit is going to remain, fixing some or all of its well-known flaws is important. (Many of which I outlined in an article back in 2017, 7 Potential Revisions To Federal EV Tax Credit.)

Fixing the flaws in the design of the credit will correct some unfairness and better allocate the credit to the right households and vehicles – but it still won’t move the needle. I hate to use an old and overused idiom, but tweaking the tax credit will be like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. It won’t solve the problem.

Section 401 of Thompson’s proposed reform seeks to fix the most widely agreed upon flaw, the 200,000 EV unit sales phaseout per manufacture.

As a reminder the federal tax credit is phased out over time beginning the second quarter AFTER the quarter in which a manufacturer reaches a total of 200,000 BEV or PHEV vehicles sold since 2010. Here is how the phase out works:

- The full amount of the EV qualifying tax credit is in place DURING the entire calendar quarter in which 200,000 EVs are sold by a manufacturer, AND through the subsequent quarter.

- Then the tax credit amount is reduced by 50% for the next 2 quarters.

- The credit is reduced again to 25% of the original amount for the subsequent 2 quarters.

- At that point the credit expires completely.

Battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles purchased in or after 2010 may be eligible for the US federal income tax credit of up to $7,500. The credit amount varies based on the capacity of the battery used to power the vehicle. Because the IRS formula is based on battery pack size, some PHEVs like the Toyota RAV4 Prime and Chrysler Pacific Hybrid are eligible for the full $7,500 credit.

The key flaw with the 200,000 unit phaseout is that it penalizes the auto manufacturers who most invested in EVs the earliest. In this case, Tesla and General Motors both of whom reached the 200,000 phaseout point – in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Tesla has now sold about 800,000 vehicles in the US and GM approximately 250,000.

The result is every other automaker can promote that its EVs (assuming they offer them) qualify for up to the $7,500 tax credit. That is theoretically a pretty significant advantage over Tesla and GM.

Following are the specific details of Thompson’s proposed reform:

Sec. 401. Modification of limitations on new qualified plug-in electric drive motor vehicle credit (§30D).

The provision expands the qualified plug-in electric drive motor vehicle credit under Section 30D to apply a new transition period for vehicle sales of a manufacturer between 200,000 and 600,000 electric vehicles (EVs), under which the credit is reduced by $500. The provision replaces the current phaseout period (which begins at 200,000 vehicles) with a phaseout period that instead begins during the second calendar quarter after the 600,000-vehicle threshold is reached. At the start of the new phaseout period, the credit is reduced by 50% for one quarter and terminates thereafter. For manufacturers that pass the 200,000-vehicle threshold before the enactment of this bill, the number of vehicles sold in between 200,000 and those sold on the date of enactment are excluded to determine when the 600,000-vehicle threshold is reached.

The provision extends the 2-wheeled plug-in electric vehicle credit through 2026. It also extends the 3-wheeled plug-in electric vehicle credit through 2026.

Would The Limitation Reform Fuel EV Sales?

There is general consensus that if the tax credit continues, the 200,000 limit is unfair and needs to be fixed. But will extending the limit to 600,000 vehicles sold threshold have a significant impact on EV sales in the US?

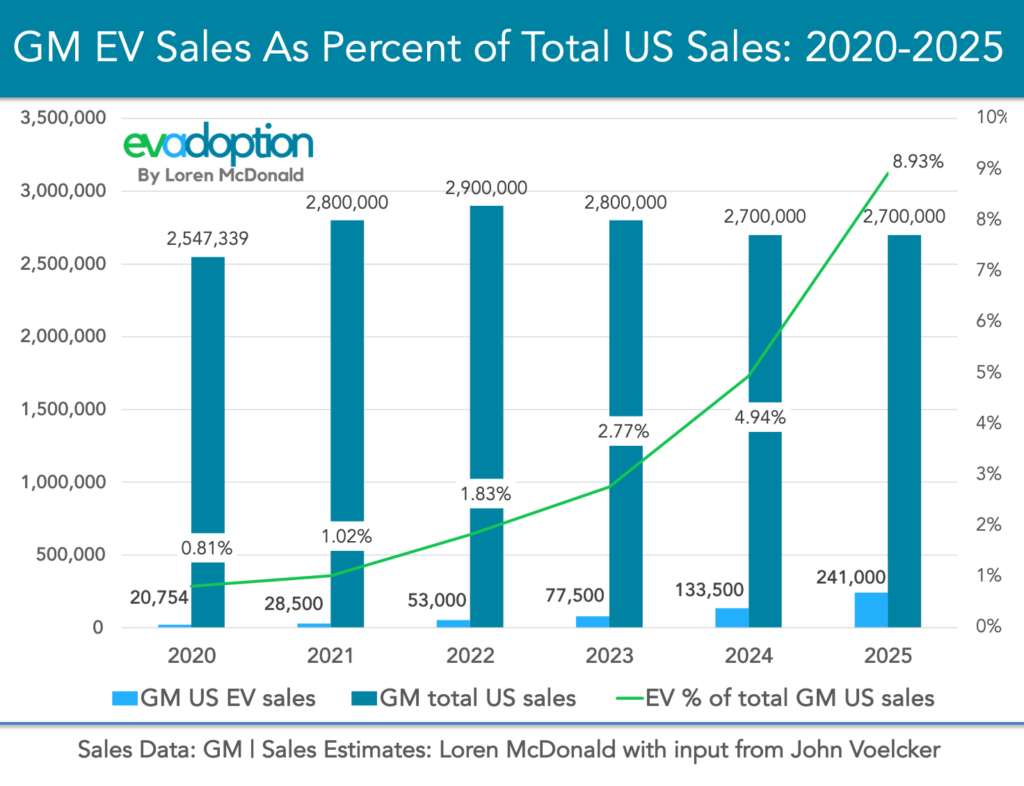

I believe the answer is no. The most obvious initial impact is that this change would increase sales of both Tesla and GM EVs. And it would boost sales slightly for the next automakers who would have reached the 200,000 limit (Nissan, Toyota and Ford).

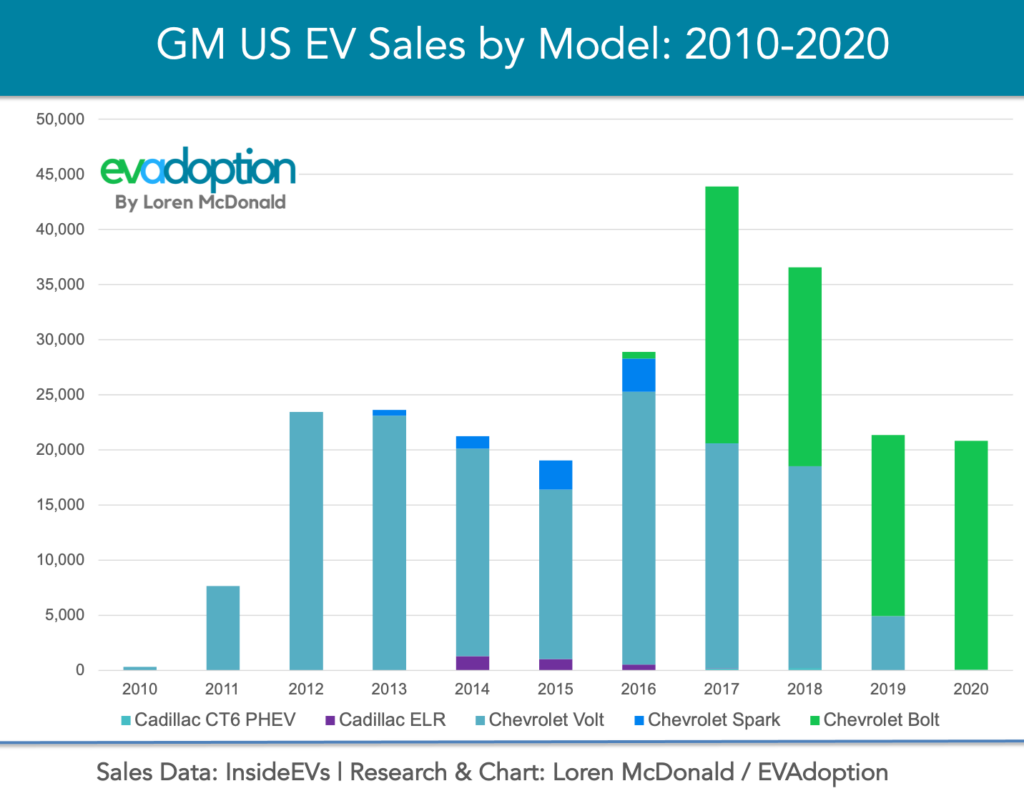

But, and while there is no way to prove this, it likely means a boost of around 10% to 20%. For GM as an example, in 2020 this would likely mean an additional 5,000 to 10,000 in EV sales. While that is a nice little bump, it amounts to a rounding error for GM.

Because the tax credit is just that – a credit you apply on your annual tax return – it can take up to 16 months to receive the benefit from the credit if you bought an EV in January and you file your return in April (the following year). And so the credit doesn’t actually reduce the purchase price of your EV (unless you lease and then finance company applies the tax credit benefit to your lease cost, reducing the monthly payment). And not all tax payers will be able to apply the full $7,500 credit (or whatever amount the EV they purchase qualifies for).

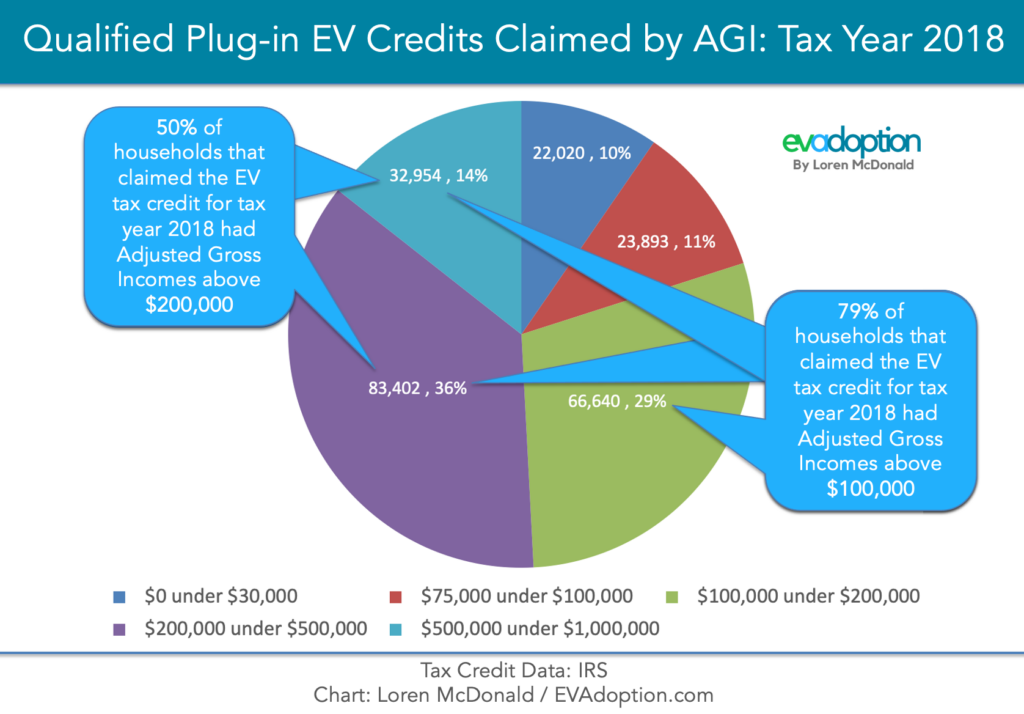

In 2018, only 21% of the tax credits went to households with less than $100,000 AGI. And 50% went to households with more than $200,000 AGI. Quite simply, the households that don’t need the tax credit are the ones taking most advantage of it. This flaw must be fixed with limits on both household AGI and a limit on MSRP of the vehicles so that the tax credit is not used by upper-income households to get a discount on their luxury EV purchase.

In the chart above you can see that once production of the Tesla Model 3 scaled up, sales rose and fell primarily based on the expiration of each phase of the phaseout. Meaning that buyers were motivated by losing some or all of the available credit.

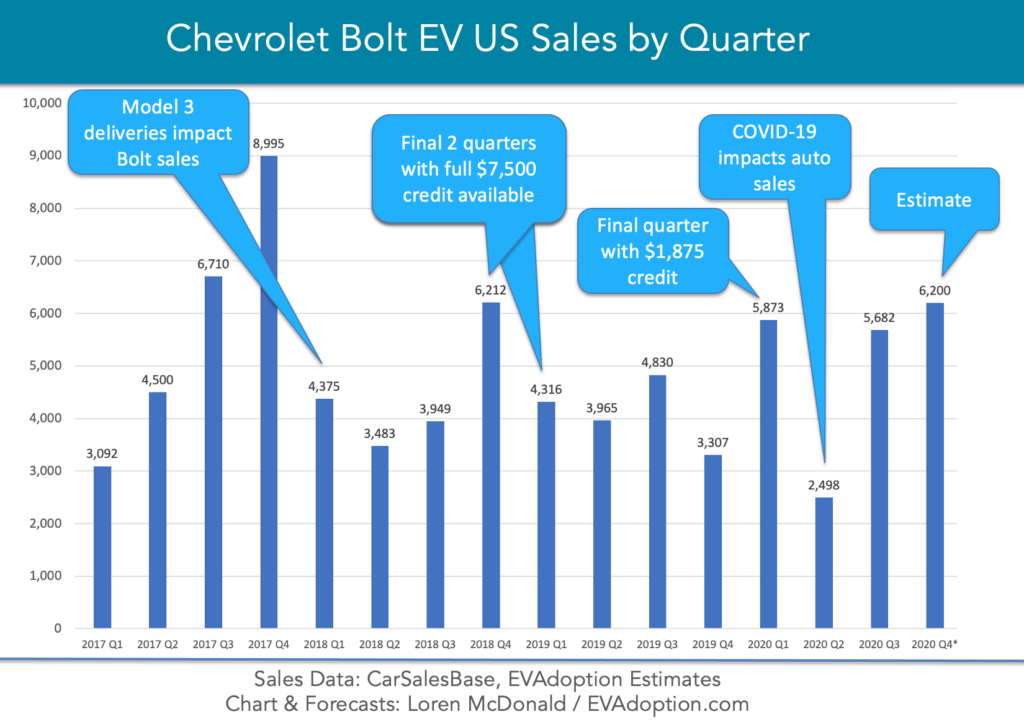

In the chart above for the Chevrolet Bolt, you see a similar trend of sales rising in the quarter(s) before each phase of the tax credit phaseout. But you also see the huge impact of competition from the Model 3 on sales of the Bolt.

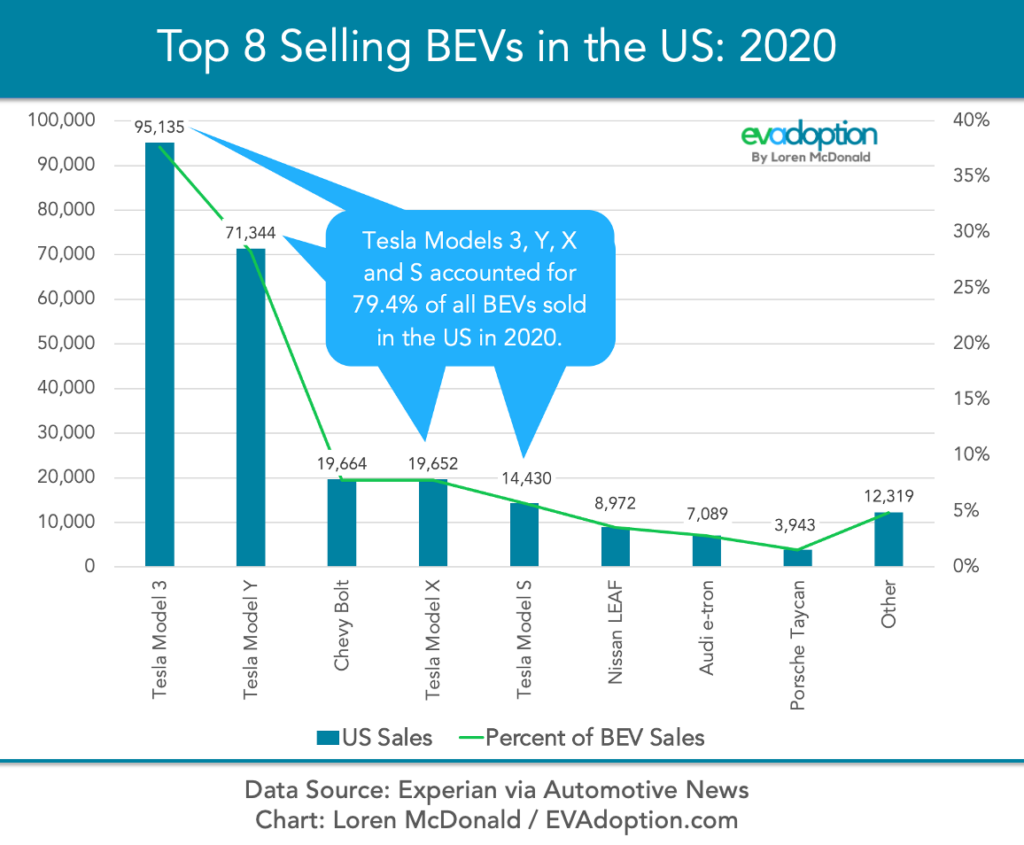

In the chart below you’ll see the that top 5 selling BEVs in the US were models from Tesla and GM – the only two manufacturers that no longer qualify for the tax credit. Say what? If the tax credit had a significant impact you would expect that models from the other brands would be more competitive with Tesla.

But the reality is, what drives sales of EV are competitive offerings and an abundant supply. Both of which have been missing among EV offerings until recently, except for from Tesla. As we’ve seen in the EU, the key to driving sales of EVs is to make the automakers increase both the competitiveness of their EV offerings and production volume – or pay significant fines.

Tax laws change behavior and in the case of the Federal EV tax credit it has primarily encouraged higher-income households to change WHEN they purchase an EV. Reforming the the current tax credit so that limit is increased to 600,000 in sales volume from 200,000 will primarily benefit higher income consumers who are likely to purchase an EV – with or without the credit.

The Federal tax credit certainly does and would with the reform increase EV sales in the US – but only at a small level of perhaps 10%-20% per year. If we are serious about driving a huge increase in EV sales, the legislative focus and Federal investments need to focus on automaker emissions mandates, increased EV charging infrastructure, and consumer education.

Note: I plan to explore Sec. 402 of Thompson’s proposed legislation that adds a new credit for previously-owned qualified plug-in electric drive motor vehicles.

9 Responses

The tax credit definitely goes into many pockets that don’t need the help, but people with lower incomes don’t tend to be early adopters of EVs. Even with the credit, the cheapest new EVs are still out of reach for many. To really be practical, you have to be able to charge an EV at home, meaning you are a homeowner, and this eliminates renters who tend to have lower incomes. Though it isn’t at all fair, it’s probably best that these credits go to folks who can afford to meld it with their own money. Lots of people who are financially comfortable are still penny pinchers, and the credit surely entices some of them to pull the trigger. I am an environmentalist who loves EVs because they don’t have tailpipes. If I could reform the credit, I would correlate the value of the credit with the MPGe of the vehicle. The best environmental use of this incentive money is to steer more of it toward smaller EVs optimized for efficiency, growing the greenest segment of the EV market. I see this as being just as important as accelerating EV adoption. MPGe matters.

Peter – completely agree. One of my recommendations in an article I wrote for CleanTechnica was to make the credit powertrain agnostic and focus it on efficiency like MPGe as you say.

While I didn’t dive into it, the incentive for used EVs in the proposal is something I’m all for.

Loren. You raise a good point that the $7500 tax credit has had only a slight effect on EV sales since the US market is dominated by high-priced EVs and high-income buyers. As the EV market transitions to more affordable EVs, the $7,500 credit can be expected to have a bigger boost on sales. You should be careful not to attribute the explosion of EV sales in Europe entirely to the strict CO2 standards. The large consumer incentives in Germany and France have also played an important role. And those incentives do have some of the restrictions that you advocate (eg price limit on eligible EVs). In China, the large EV purchase incentives have also played a significant role boosting EV sales, especially in the middle and lower price ranges. There is no magic bullet to achieve mass commercialization of EVs in the US: it will take a combination of pro-EV policies. John

Agreed John. But the emissions standards is what drives the supply from OEMs which is the most important driver of EV sales. In the US, state and utility rebates have an impact – which are important like the incentives in Germany, etc. But the Federal tax credit just hasn’t had any significant impact.

In the US, the IRS numbers don’t lie – the tax credit has mostly gone to households that don’t need the incentive.

Yes, Loren, driving supply is important as well as driving demand. Why do you think that the state and utility rebates are more important than the federal credit? The federal credit is much larger!! John

What is your current EV sales estimate for 2021? You published an article, I think in October 2020, estimating 585,000 EV sales in 2021. That was before the presidential election. New model launches have been announced since then. Youg got more details about GM’s plans etc.

A few days ago IHS Markit published and article estimating a 3.5 % market share on a national level in the US in 2021 for pure electric battery vehicles. IHS Markit also forecasts 16 million vehicle sales in the US in 2021. That means roughly 560,000 pure electric vehicles. No figure for (plugin) hybrids was given.

https://news.ihsmarkit.com/prviewer/release_only/slug/bizwire-2021-2-19-electric-vehicle-share-in-the-us-reaches-record-levels-in-2020-according-to-ihs-markit

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/sneak-peek-2020-u-auto-125112814.html#:~:text=Per%20IHS%20Markit%2C%20U.S.%20vehicle,year%20to%2016%20million%20units.

Stephan, thanks for the question and detail. I will be doing an updated analysis and forecast for 2021 later in March – but I don’t anticipate a significant change from my previous forecast. While more EVs have been announced, many will be delayed or arriving late in the year in small quantity – we still haven’t seen any volume from the Toyota RAV4 Prime and unsure when the Ford Escape PHEV will reach dealers due to the Kuga fires in Europe. And any impact from the Biden administration aren’t likely to take effect until 2022. But thanks for the ping and check back in mid-to late March.

Loren

Good piece.

We advise auto suppliers on BEV RFQ proposals.

I would emphasize the price/value of BEV versus ICE, recharging time for 100 miles and number of charging stations as a % of gasoline stations in the city and highway (separate calculations). These factors are superior to the ones you listed as demand drivers. Consumers don’t want gas pumps in their garages, and don’t want charging stations either.

The ROI of penalties for not meeting CO2 vs. price reductions without tax credits will be a lens that manufacturers will look at moving forward.

Warren, thanks for the comment. I do, however, disagree with a couple of your points. I’ve never heard of an EV owner (myself included) that didn’t LOVE having charging stations in their home. If you live in a SFH, being able to plug your EV in every night and not have to go to a gas station is one of the best parts of owning an EV. So completely disagree with you on that point.

Secondly, there is no correlation between gas stations and charging station locations – how we refuel EVs is very different from how we refuel gas cars. So the ratios are very different.