Last week Ford released photographs of a prototype electric F-150 pickup and a video of the iconic truck pulling rail cars weighing 1 million pounds. (You can read my in-depth article on CleanTechnica, Breaking! Video & Photos Of Fully Electric Ford F-150 — Pulling A Train.)

The reactions from people tended to fall into one or more of the following camps:

- Phooey. Pulling rail cars on tracks is easy, people can do that. Let me know when you can pull a huge amount of dead weight for an extended period of time. (There is also this reaction from Road & Track – Ford’s Train-Towing Electric F-150 Stunt Was Way Easier Than it Looked)

- Yawn. Another prototype EV from a legacy automaker. No details, no specifics on when it will reach market, other than “in a few years.” Let me know when you are about to actually release it.

- Blasphemy. Come talk to me when an electric F-150 has 500 miles of range, can charge to a full battery in 5 minutes, can handle freezing temperatures, and there are plenty of places to charge out in rural areas.

- An electric F-150 could be game changing. If pickup lovers see that even their beloved F-150 has gone electric, many reluctant EV buyers may actually consider buying an EV.

Of those four reactions, I personally came closest to feeling the most like the last point. From my CleanTechnica article:

In 2030, when observers look back on the previous 20 year history of EVs in the US, the electric Ford F-150 may viewed as a key vehicle that ushered in mass adoption of EVs. Key, of course, will be the truck’s price, range, and availability.

But I’m actually not convinced that an electric F-150 is what America needs in the next few years. In fact, if the specifications on the electric F-150 fall short of market expectations and needs, the vehicle could do more harm than good for EV adoption.

Look at some Twitter exchanges I had with a few folks in response to my CleanTechnica article:

According to Hedges & Company, some key demographics of new F-150 buyers include the following:

- 84% are male

- Average buyer is 55 years of age

- Nearly three quarters are white males

- Average annual household income is $82,000

- The vast majority of these new trucks are purchased in large and medium-sized cities (Hedges did not include any actual percentages).

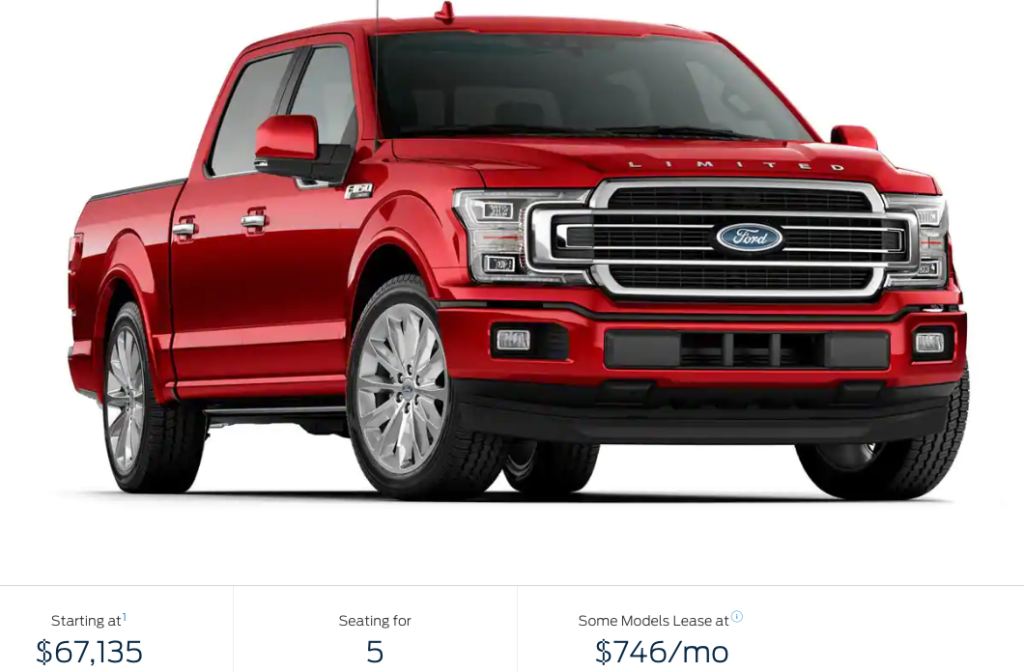

And according to Kelley Blue Book, the average transaction price of a 2018 Ford F-150 was $47,174 and add on taxes and fees, and “suddenly a $50,000 pickup truck is the new norm.”

While people like to stereotype pickup buyers, except for being mostly white males, they aren’t just driven by blue-collar workers and farmers. In fact pickups are very popular in many suburban neighborhoods as people love the utility of pickups for towing trailers, hauling dirt bikes, trash or lumber on weekends, going camping in the summer or skiing in the winter.

But that said, pickup owners are likely to be the last buyer group to purchase an electric vehicle. Pickup drivers by their very nature don’t want any compromises in the vehicle they purchase. And let’s be honest, electric vehicles will not have the range of gas-or diesel-powered trucks for another 5-7 years or more – and if they do it will come at a significant price premium. And telling a pickup owner to charge while they eat, work or shop is not what they want to hear – “Call me when an EV charges in 5 minutes” many will say.

Alternatives Ford Could Consider

Pickups have been strong sellers in the US for years. In fact, the Ford F-150 has been the number one-selling vehicle in the US for 42 straight years. And so far in 2019 according to GoodCarBadCar.net, the top-3 selling vehicles are pickups: Ford F-150, Ram Pickup, and Chevrolet Silverado.

The F-150 will likely see sales of well north of 800,000 units in 2019 and in 2018 more than 2 million US consumers purchased one of the big 3 pickups, according to the Detroit Free Press:

- 909,330 Ford F-Series

- 585,581 Chevrolet Silverado trucks

- 536,980 Ram Trucks.

But are American truck buyers ready for their iconic and beloved F-150 to go electric? While there will clearly be a small market – perhaps up to about 20,000-30,000 units annually – for a BEV F-150, those numbers will almost be a rounding error for Ford accountants.

Until battery prices come down and make a $50,000 electric pickup with 450 miles of range possible, electric pickups will most likely be a niche product in the US. And if Ford’s first attempt at an electric F-150 falls short of market expectations, it could actually do more to hurt than help the transition to EVs. If the F-150 has mediocre specifications, but has a base cost of say $50,000-$60,000, EV naysayers will point to the F-150 as another reason EVs aren’t ready for prime time.

Ford is also launching a regular gas hybrid F-150 sometime in 2020. If gas prices rise in most of the US above $4 per gallon (they already are at that level in California), then a regular hybrid version could sell fairly well – especially if priced below the turbodiesel powertrain option. The hybrid could be attractive to fleet owners who are focused on total cost of ownership and construction companies will like the ability of the hybrid to function as a mobile generator at a job site.

So what should Ford do? Here are a few ideas:

Launch a new Raptor-like model brand: Ford’s very successful supercab Raptor version of the F-150 starts at about $55,000 and can easily reach $70,000. Yes, for a pickup. In many ways, trucks like the Raptor are the new muscle cars. They are aspirational vehicles for (mostly) males to make a statement with their vehicle.

Ford’s competition for an electric F-150 will likely not be the Ram and Silverado trucks but rather electric offerings from Rivian and Tesla. Ford should not initially compromise and come to market with a decent offering with say 300-325~ miles of range. But rather the company should come out with a Raptor-like equivalent with a new and similar model brand that makes the offering the meanest, baddest truck on the market – whether electric, gas or diesel.

This means it should have at least 400 miles of range, be faster than a big-block Mustang, and able to tow a jet. It should make truck buyers jaws drop. Yes, this means its starting price might be $60,000-$70,000. But so be it. It needs to exceed expectations, not be a ho-hum truck that makes people snicker and decide to buy a Ram gas or diesel truck instead.

Launch it as a Lincoln, not a Ford: Because of the price differential between ICE vehicles and EVs, most automakers recognize that at this stage of the EV market, launching EVs under luxury brands is the smart way to go. Because most initial consumer (as opposed to fleet) buyers of electric pickups will be suburban weekend warriors, Ford might consider releasing the electric F-150 with a different model name underneath the Lincoln luxury brand instead of the Ford brand. As a Lincoln, range and price of the truck will be less of an issue for buyers. And its presumably more expensive price point would also be more acceptable as a Lincoln than a Ford.

Ford Ranger, not F-150: Ford recently reintroduced its smaller mid-sized pickup, the Ranger. The Ranger might be the better pickup to launch as an EV. As a mid-sized pickup it can get by with a shorter range but it also likely appeals to a more suburban, commuter market. Expectations won’t be as high for the Ranger as they would be for the F-150.

Launch the F-150 as a plug-in hybrid: Ford has apparently locked down a two-pronged new powertrain approach for the F-150 – a regular hybrid and the all electric version. It is unclear how much of Ford’s decision to produce a BEV version is based on having a response to the upcoming BEV pickups from Rivian and Tesla, or is a mostly independent strategic decision?

And while likely too late to shift plans at this stage, I have to wonder if a PHEV version would be better received by the broader pickup-buying market at this stage? A BEV version of the F-150 is likely to have a range of 300-350 miles (a pure guess since Ford has not released any details) and cost $50,000-$60,000. Compare that to a range of about 450 miles for a gas-powered version – and even at a similar price – and the electric F-150 falls short in comparison. While pickups are in essence commuter vehicles for many owners, having well north of 400 miles of range is what these buyers expect from their pickups.

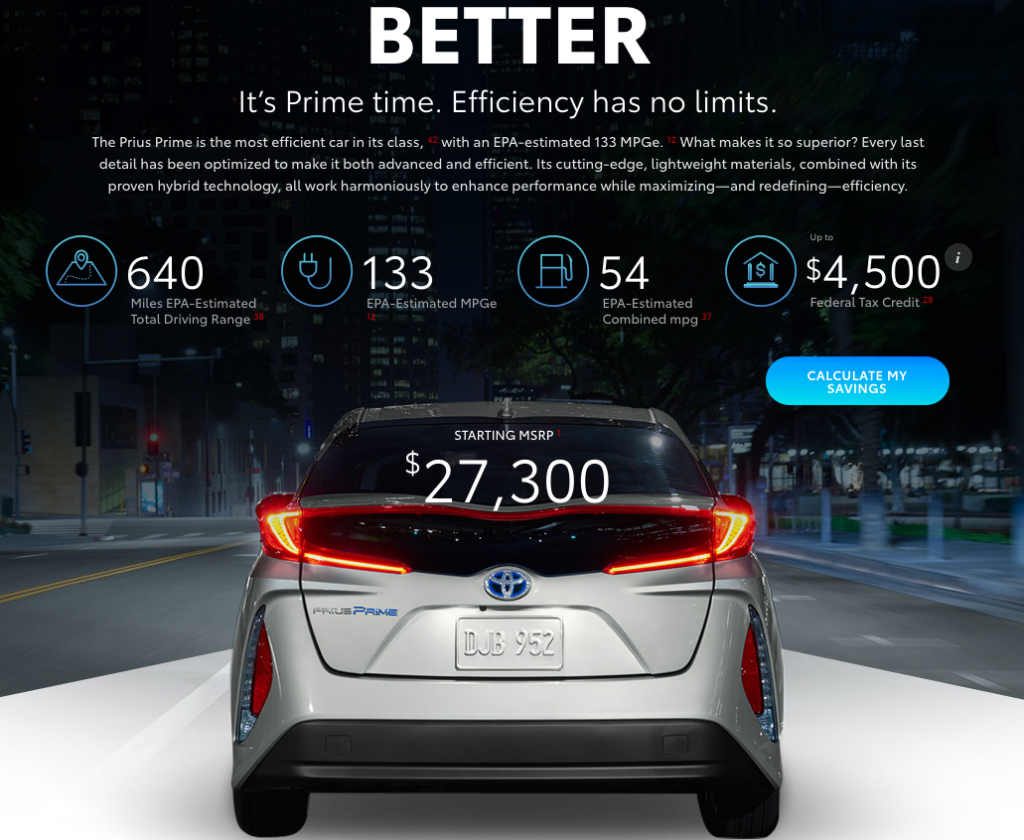

What if Ford produced a PHEV version that actually had MORE combined range than the gas version? As examples, the Toyota Prius Prime has an EPA range of 25 miles, but a combined gas and electric range of 640 miles. The Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid (PHEV) has a 32 mile electric range and 520 miles combined.

What if Ford brought to market a PHEV pickup with say 30-35 miles of electric range and 500+ miles of combined gas and electric range? A PHEV model would then shift the narrative from being inferior to the gas-only version, to one of superiority and also eliminate concerns around range and charger anxiety.

As excited as I am about an electric Ford F-150, if the pickup falls short of expectations it could hurt the EV movement rather than move it forward. Ford may want to consider one of the above options instead.

3 Responses

I saw no comments in support of an EV truck from the standpoint of operating cost – especially fuel cost. That is where EVs have a real advantage over ICUs – now, today. Electricity is basically cheaper than gasoline or diesel on a comparative basis – and the cost of electricity does not fluctuate as much as gas or diesel. Over the course of a year; several years, these savings are real. Also, EVs require no oil changes and less regular maintenance. There are fewer things to break. More needs to be made of all these things to the detractors.

One point and one question: First, the point: based on the demographics you cite (and my own observations) of typical pickup truck owners (eg. white males), they seem to be more conservative in their views and so are likely to be the LAST consumer group to covert from ICU to EV. Some may even be openly opposed to EVs on political grounds. Now the question: why try and sell to these guys first? Why not go for the lower-hanging fruit first – the SUV drivers – many of whom are suburban moms who drive a lot – but not likely 400 miles in a single day (at least not often) and so can easily recharge every day? What about a mix of BEV, PHEV or HEV Ford Explorers/Escapes or Honda Pilots/CR-Vs or Chevy Blazers/Equinoxes/Tahoes?

Nmexander, yes I agree that pickup drivers will be one of the last segments to buy EVs … that is one of my main points ,,,, and agree, the focus needs to be on SUVs and CUVs in the near term.

If they make a reasonably priced version of this, it could be a hit with fleet and business users, for example, tradesmen who have a limited territory and go out every day to do whatever they do. There are also gazillions of F-150s and similar vehicles owned by apartment complexes, towns, cities, parks and rec departments, private institutions, marinas, that often don’t go more than a few miles away from their home base, but rack up constant miles back and forth and to local businesses to pick stuff up. These applications would be ideal for a BEV, even one with 150-200mi of range, as long as they have the range and towing capacity necessary for that type of work. They would also do a lot to reduce local emissions, as those vehicles idle a lot and get even worse gas mileage than your average F-150, since they do so many very short trips. The same logic applies for work vans and even passenger vans and busses that often operate in very small, confined routes where they can be brought back to their home base every 100-200 miles for recharging.