One of my biggest pet peeves in the EV industry is when people compare “EV stations” to “gas stations.”

It just isn’t that simple and you can slice this type of comparison about 10 different ways to make the data tell whatever story you want. Let’s look at a recent example from the November 29, 2022 Wall Street Journal article (subscription may be required): “Why America Doesn’t Have Enough EV Charging Stations“:

“There are more than 145,000 places to refuel a gas-powered vehicle. So far, the U.S. has 11,600 points where any EV can charge quickly, according to the research group Atlas Public Policy.”

First, let me make it clear – we absolutely do need a lot more public chargers/pedestals/ports (“station” is the term for location, like a “gas station” – but let’s put that nomenclature mess aside for now). Second, the current state of public charging outside of the two Tesla networks is generally considered a mess, with reliability being a significant issue.

EVs Have a Better Ratio to the Number of Charging Stations Than ICE to Gas Stations

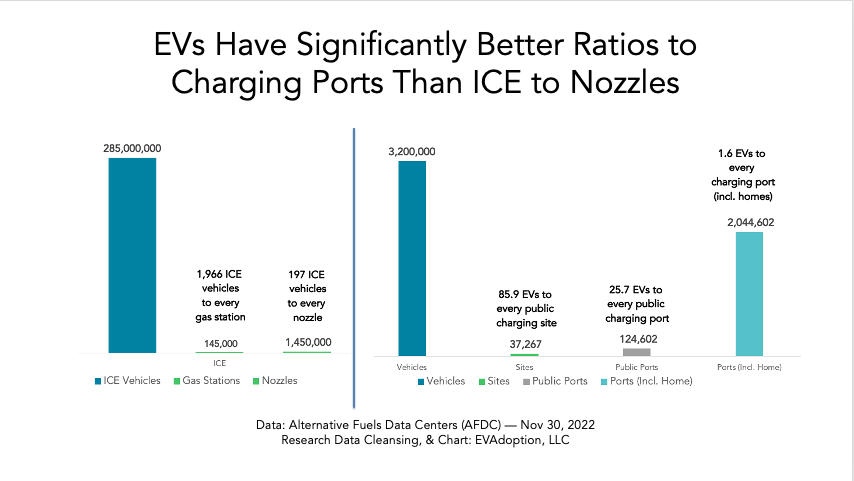

OK, let’s get back to the math. Regardless of how you slice the data, electric vehicles (I’m including both BEVs and PHEVs) today in the US have a better ratio to charging stations (site/locations) than ICE to gas stations. And also public Level 2 + DCFC ports versus gas pump nozzles. And significantly better ratio if you you count public Level 2 + DCFC + residential changers. For this I have used 60% of total EVs on the road to estimate the number of EV drivers with access to charging where they live.

Notes: I recognize that PHEVs can’t charge at DC fast chargers so this math is not perfectly correct. But if you remove PHEVs from the EV count, then the BEV to charging port ratio gets even better. Secondly, yes I know that non-Tesla EVs can’t charge at Tesla chargers. But if you separate Tesla and non-Tesla EVs, the ratios are still pretty close to the overall but very slightly in the grand scheme.

If you drive a gas-powered vehicle, there are 197 vehicles to every gas pump nozzle. If you drive an EV, there are 25.7 EVs to each public Level 2 + DCFC port, and 1.6 to 1 if you include those chargers at home where you park your car each night.

Residential Chargers Must Be Included in the Comparison

Remember, those people who can charge at where they live (whether a single family home, apartment, or condominium), most, not all of them will do so regularly and rely on public charging minimally — except for when taking medium to longer trips. Yes, there are of course exceptions such as my Tesla Model 3-driving neighbor with the 3-car garage who for some reason regularly charges at a Tesla Supercharger near his office (which reduces the battery life of his EV). Or people who drive long distances regularly. But these tend to be in the minority.

Any owner of an EV that has access to charging where they live will tell you that is one of the single biggest benefits of driving an EV. You plug in and go to sleep and wake up with a fully charged EV. Now if you live in a condo, or apartment, or downtown urban setting without a garage or driveway, then you of course do have to rely on workplace and public charging.

And so IMHO solving that issue is actually a bigger need than DC fast chargers out on some highway. Yes, those too are really, really important to get people comfortable with the idea of taking road trips. But if someone cannot conveniently charge where they live — then they are missing out on one of the biggest benefits of driving an EV. Back to main point of this rant …

STOP COMPARING CHARGING STATIONS TO GAS STATIONS!

Multiple Variables When Comparing Charging Stations to Gas Stations

There are multiple combinations of ways you can make the comparison between refueling and ICE vehicle and an EV. But at its foundation, you MUST include the ratio of the number of vehicles on the road today. And there are roughly 285 million gas-powered vehicles and about 3.2 million EVs (including PHEVs). So of course there are going to be fewer charging stations than gas stations. So it isn’t just the number of vehicles that have to be included in this often used and misused comparison, but also must incorporate ALL types of chargers. That means including public Level 2 and residential chargers and not just DC fast chargers as these non-fast chargers are how EVs are charged most of the time.

Now, a relevant comparison or metric would be using the number of BEVs that travel on highway corridors and the number of DC fast chargers available versus gas cars and gas stations. But that gets at some pretty complex data. Additionally, as many people pointed out on my original LinkedIn post (upon which this article was based), additional factors need to be included in any type of gas versus charging station comparison, including:

Refueling Time: It takes about 5-7 minutes depending on the size of your gas tank and fuel level to refuel it. EVs have similar, but even more variables beyond the size of the battery pack and state of charge (percent charged). This includes the power level of the charging hardware, if the charging pedestal has two ports and the power is shared across the ports, the maximum charging capability of the EV, its charging curve, the ambient temperature, whether of not the battery was pre-conditioned, and more. So for an EV it might take 15-20 minutes to reach 80% (or more) or it might take more than an hour.

But, and a big but, is that experienced EV drivers plan their meals, shopping, and other activities first and foremost — and then their EV charges while they do these other activities. So if you plan correctly, your EV will reach the desired battery state of charge level at about the same time (of before) you are finished eating or shopping. This approach won’t work for everyone of course. But personally in several road trips I’ve done with my wife and daughter, we’ve generally only had to wait 10 minutes or so after finishing our meal.

Reliability: Someone else pointed out the current issue of many EV charging units not working or unavailable. And this is true. With gas pumps they rarely seem to be broken and if one is there maybe 7 or 9 other ones working. While it is going to take a few years for DC fast chargers to become more reliable, I believe the industry will eventually become nearly as reliable as we see with gas pumps.

So for a much more accurate comparison between gas stations and charging stations, refueling time and uptime would also need to be factored into the math — in addition to the number of vehicles on the road and ALL types of chargers. But again, this was my ultimate point — not the ratios in the chart — but rather that making a very simple comparison like what was done in the Wall Street Journal article, is just meaningless. I’m generally also not a fan of using ratios, unless they are confined to very specific region, use case, and type of vehicle and charger type.

In a future article I will write about all of the variables that actually determine how many EV chargers are actually needed in the US.

2 Responses

I agree the issue is sort/medium distance charging and “filling up” while on a long trip. The metric for long trips is probably the distance to the next Charger on the “major” roads (not an easy thing to calculate)… in the mean time the miles of “major roads” to EV’s would be a good interim metric

My comment should read the ratio of miles of major roads to fast EV chargers and then compared to EV’s. It won’t directly compare to gas pumps but gives one an estimate of distance between EV fast chargers