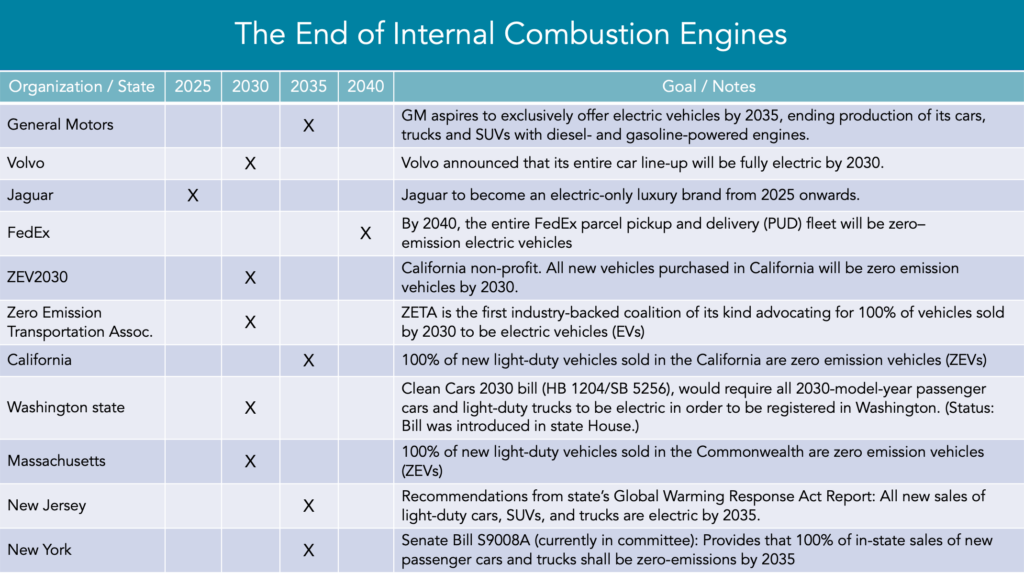

2025. 2030. 2035. 2040.

These are all dates that various automakers, electric vehicle organizations, and states have declared when they want to ban the sale of or end their production of vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine.

Reducing carbon omissions and pollution from the transportation sector are clearly important to the health of the planet and humans. And achieving these reductions is impossible without aggressive goals and regulations that drive behavioral change among both automakers and consumers.

Key questions, however, is are these goals of banning/ending production of ICE vehicles by 2030, 2035, or even 2040 actually realistic and what would it take to reach them?

I will continue to dive into these and other key EV adoption questions in the coming months, but with this article I will share some notes and thoughts on some of the near- and longer-term challenges getting in the way of achieving these goals.

EV Price Parity With ICE Vehicles Is Fast Approaching

A lot of electric vehicle observers, analysts, and pundits like to say that, “When electric vehicles reach price parity with ICE vehicles – it’s game over gas-powered vehicles.” Unfortunately it isn’t quite that simple.

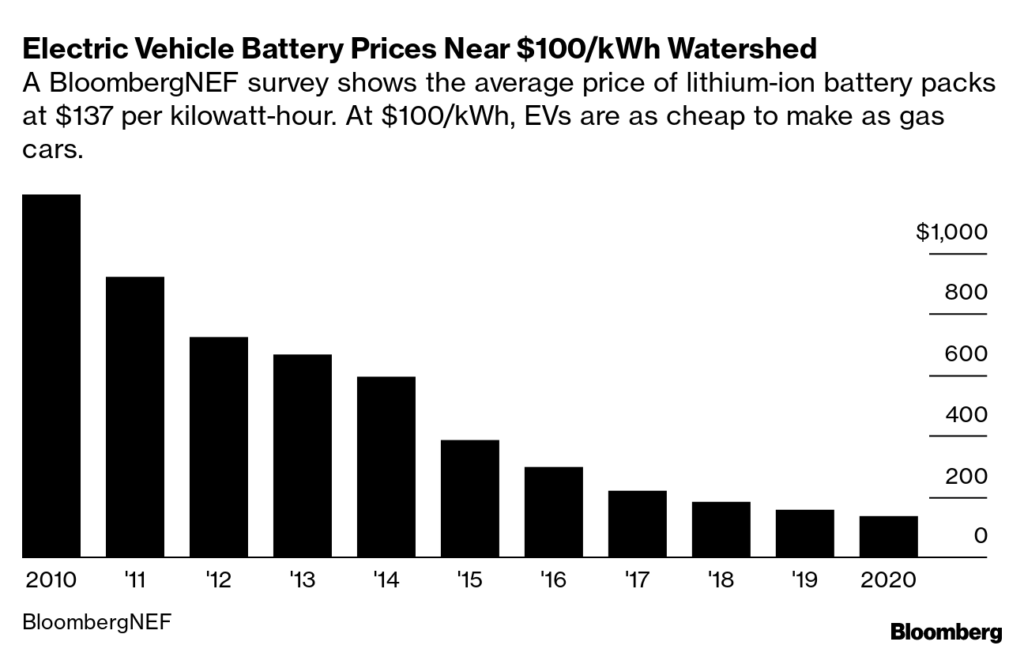

According to a price survey conducted by BloombergNEF, automakers soon will be producing models that are “as affordable—and as profitable—as comparable combustion engine models, and without the help of tax subsidies.”

According to the survey of nearly 150 buyers and sellers by BloombergNEF (BNEF), the average price per kilowatt-hour for a lithium-ion battery pack has declined to $137 in 2020, down 13 percent from $157 in 2019. In 2010, these batteries sold for more than $1,100 per kilowatt-hour.

Many industry analysts, including and most notably BNEF, say that the threshold for price parity with gasoline engines is around $100/kWh and they expect battery makers to hit $101/kWh in 2023.

“For many vehicle segments, (reaching price parity) it’s in the next three or four years.”

– Logan Goldie-Scot, head of clean power at BNEF

According to BNEF, even if prices for nickel, cobalt, lithium, and other raw materials used in batteries return to the highs seen in 2018, $100/kWh packs would be delayed by only a couple of years.

Because battery packs are the single most expensive part of an electric vehicle, typically accounting for roughly 30 percent of the total retail price of an EV – price parity is of course key to mass adoption. But at many levels, price parity may be the easiest part of the EV adoption equation. And at a fundamental lever, battery prices are more important to EV adoption for the automakers than consumers. Because of the high cost or batteries, many automakers have basically sat on the sidelines as they wait for prices to come down before jumping in to EV production with both feet.

Lower battery prices – and hence EV price parity – is simply a function of continued battery chemistry innovations, increases in energy density, increased competition, and scaling up manufacturing. As the BNEF chart above shows, getting to price parity is simply a matter of time – likely 2023 to 2025 for many automakers.

The fundamental point being that while achieving at or near price parity is clearly important for mass consumer adoption, the first challenge is just producing enough batteries to meet the potential demand in the US in the coming years.

They’re currently aren’t enough batteries to meet the global demand for EVs. Automakers with a major presence in Europe are sending the majority of their electric vehicle models to the EU market in order to ensure they meet the emissions mandate requirements, often leaving a minimal volume of EV models to ship to the US.

BMW, Mercedes, and Volkswagen have all not shipped certain electric models to the US and Toyota is shipping the majority of their RAV4 Prime PHEVs to Europe and Asia. And Hyundai and Kia models tend to be in low supply for the US, which is now compounded by Hyundai’s complete recall of 76,000 Kona EV models due to a battery issue that caused several fires.

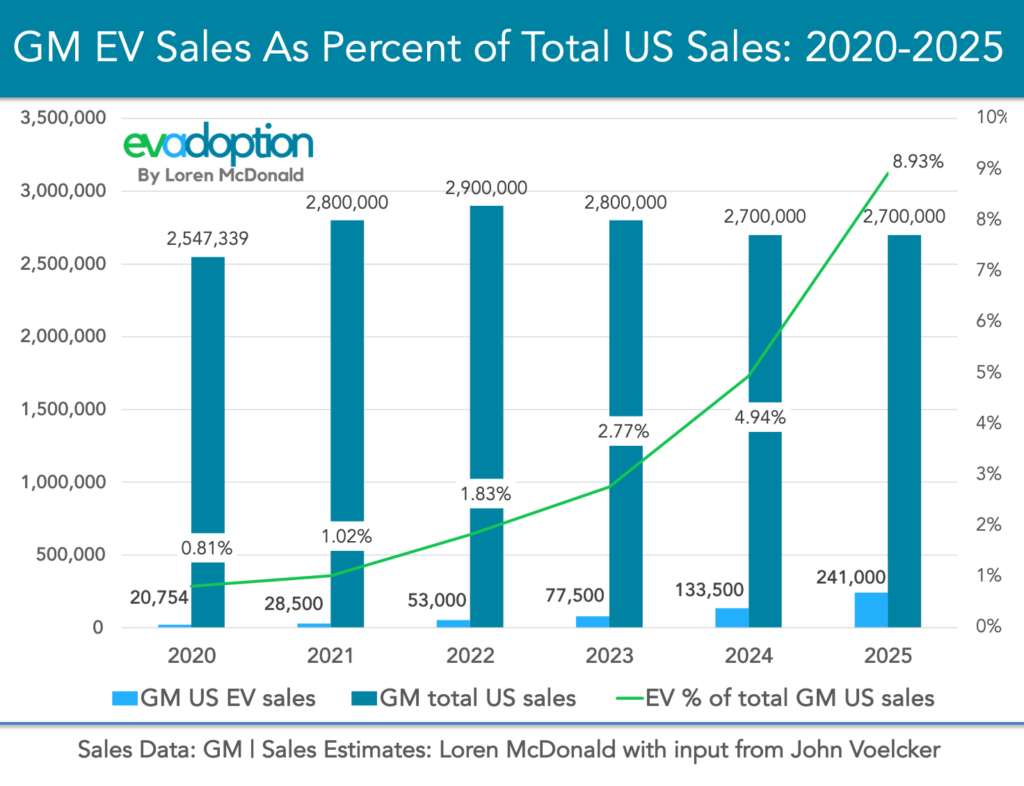

In my recent article analyzing GM’s plan to launch 30 new EV models globally by 2025 and my assumption that 20 of these would be available in the US, the actual volume was minimal and well less than 10% of GM’s estimated total sales in 2025. But just this past week GM apparently confirmed plans to build a second US battery factory in partnership with LG, perhaps a recognition that demand may outstrip their future planned battery supply.

It’s the batteries stupid. Price matters, but supply is probably even more important.

Five Core Challenges Holding EV Sales Back in the US

While reaching cost parity is clearly critical, almost foundational to achieving mass adoption of electric vehicles, the more difficult challenges tend to fall into two camps: supply and consumer awareness and acceptance.

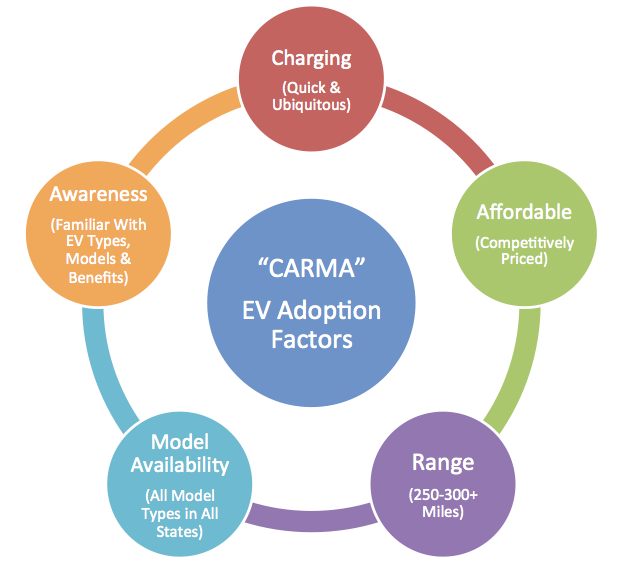

In my very first article for this site and blog back in January 2017, I created a framework of factors that were critical for EVAdoption in the US (chart below).

Four years later, there is very little I would change with this model, except perhaps a greater emphasis on “Awareness” from the perspective of consumers becoming more aware and comfortable with the concept and process of refueling their vehicle with electricity.

Let’s take a quick at where we sit in 2021 relative to the CARMA factors:

C = Charging Speed and Availability: Building out the necessary EV charging infrastructure in the US is of course a bit of the chicken or the egg. Many consumers won’t buy an EV until they feel comfortable that wherever they drive there are plenty of available fast charging stations. At the same time, EV networks have yet to make any profits even with significant public and private funding, they can’t expand too far ahead of demand.

As Jonathan Levy, chief commercial officer at the fast-charging network EVgo said in a recent Business Insider article, “There are risks to building too many charging stations too quickly. Charging infrastructure needs to stay just ahead of EV ownership and demand, not drastically outpace it.”

Levy added that it is because overbuilding can crater the economics of the charging business, leading to large numbers of stations that are underutilized and unprofitable to operate. And finding the right profitable business model among the EV charging networks remains, -and likely will continue to be, a challenge at the for some time.

In higher EV-adopting areas of the US such as many parts of California, there tends to be an adequate number of EV charging stations – especially if you drive a Tesla. The shortfall tends to occur on busy holidays, peak commute times, and with DC fast chargers for non-Tesla drivers on interstates and road-trip routes. But with hundreds of millions and potentially billions of dollars from states, municipalities and the federal government flowing in, especially to build out DC fast charging stations, the supply of public fast chargers should keep pace with or stay ahead of demand in the coming decade.

However, one of the biggest hurdles to mass adoption of EVs is with the estimated 40% of US households that do not have convenient access to EV charging due to living in an apartment or condo, or not having convenient street parking or workplace charging access.

Anyone who drives an EV and charges their car through an outlet or EV charging equipment in the garage every night knows how simple and convenient it is to refuel your car. As many EV owners like to say, “Happiness is never having to go to a gas station.” In other words one of the single greatest advantages of EVs is the simplicity and convenience of plugging in your car in the evening and waking up with a full, or near full charge the next morning.

But if you don’t have that type of convenient access to charging you must rely on workplace or public charging stations which then turn the overnight charging advantage into a disadvantage and which is then less convenient than having to go to a gas station. Ugh.

Ground zero for most of these households is the reality that apartment and condo owners are generally reticent to install EV charging stations because of the high cost, along with parking and tenant management hassles.

In fact, until apartment owners embrace EV charging as an amenity and charging options get built out on street parking and at the workplace, mass adoption of EVs will but limited. There are some emerging solutions, however, that could see apartment property owners begin to offer EV charging to their tenants.

One company, Low Power EV Charging (LPEVC), offers a Level 1 120 volt smart outlet from Plugzio, plus dedicated parking and an outsourced management solution to apartment property owners. The approach cuts the cost of charging ports and installation to about half that of Level 2 equipment, making offering charging as an amenity much more attractive. And having a dedicated parking space where an EV-driving tenant can have confidence they can charge every night is exactly the experience they seek. (Disclosure: LPEVC is an EVAdoption client.)

Similarly, while there is considerable focus on building out DC fast charging and Level 2 charging infrastructure, there is a tremendous opportunity to add more affordable public Level 1 stations. Level 1 can be ideal where people park their car for eight or more hours during the day such as at their place of work, mass transit parking lots, and colleges and schools. Less costly Level 1 charging can add 40 miles of range while the car is parked. And when drivers need additional range for longer trips, they can simply visit a nearby fast charging station.

The second aspect of charging is speed. Super fast charging stations that can charge at rates of 250 kW or even higher are being rolled out, but there are few EVs that currently can actually accept these rates. Fortunately, many of the new EVs coming to market now and over the next few years will be able to charge at these faster rates and enable drivers to add 200 miles of range in less than 30 minutes.

As consumers understand that charging is different from refueling with gas – you charge while you eat, shop, sleep, and relax – being able to add 200 miles of range in 20-30 minutes will be acceptable to most buyers. But until super fast charging locations are ubiquitous and most EVs are capable of accepting 250 kW rates and higher, many buyers will sit on the sidelines.

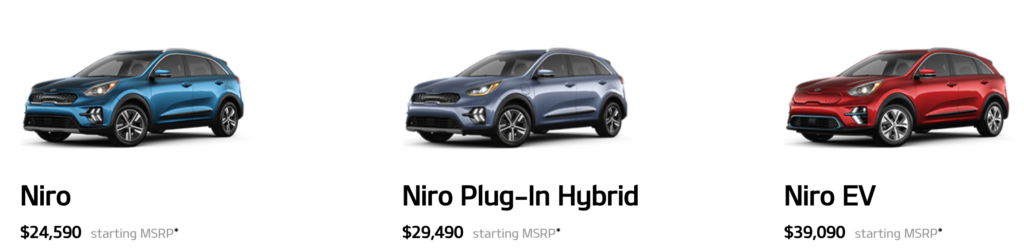

A = Affordability: While BNEF says we are only 3-4 years away from price parity between ICE and BEV versions of models, you wouldn’t necessarily know it by comparing different powertrains of the same model from many brands today.

The price differential between gas and electric versions of the same models or comparable models is often $5,000 to $10,000 or more. However, between federal, state, and utility incentives and savings on gas and maintenance, in many cases the cost differential is zero or very small. And if you factor in the fact that EVs are simply better vehicles than gas-powered cars, even if the net cost of an EV is a bit more you’re actually driving a superior vehicle and so in my mind it should cost a little more – at least at the present and for a few more years.

Unfortunately, many automakers do a disservice to EVs and create competition among their own offerings. The base version of the Kia Niro, for example, is a hybrid but it also comes in PHEV and BEV version. Not including incentives, the BEV version starts at $14,500 more than the hybrid version. Ouch. Again, fortunately most automakers are now bringing new, standalone EVs to market and as such their prices will be compared to other comparable EVs, rather than similar ICE vehicles.

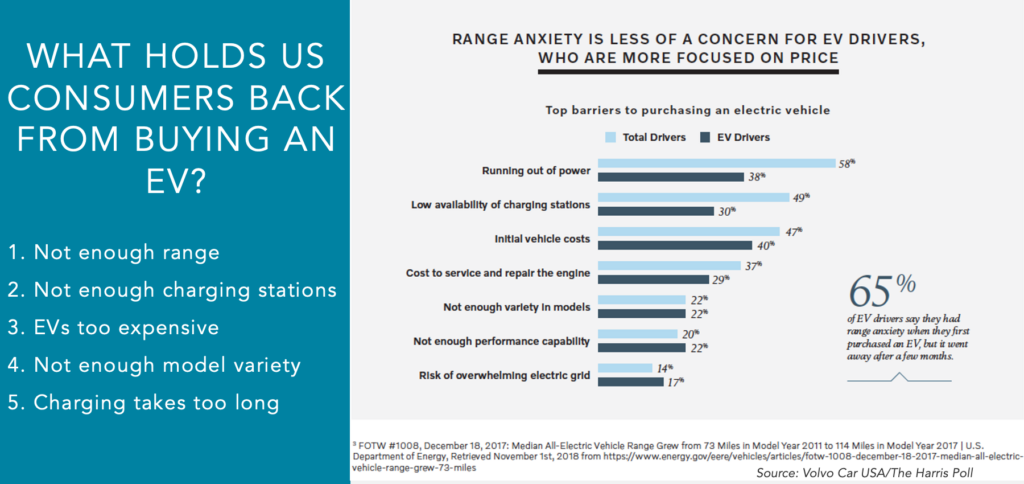

R = Range: Range anxiety is simply a more basic concern for consumers before they will even consider an EV – let alone be concerned with price.

A large percentage of potential EV buyers want or expect 300 to 400 miles or more of range for the simple fact that is the range their gas- or diesel- powered vehicle has. This is what they’ve been accustomed to forever and EV range that doesn’t compare with their gas vehicle is simply a nonstarter before even price and model type are considered.

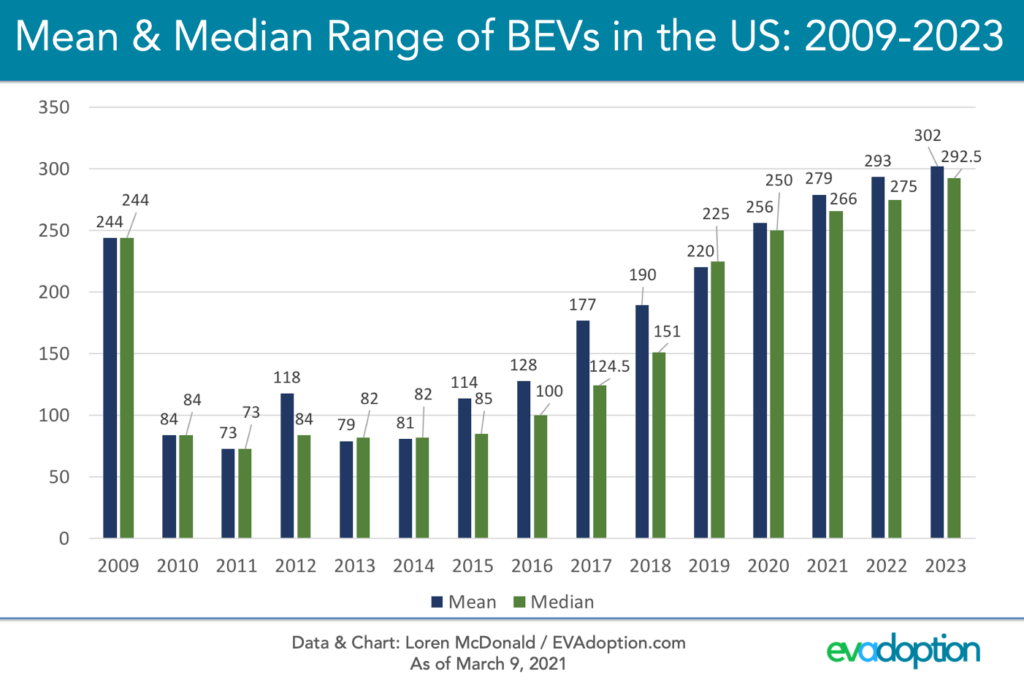

For many vehicle owners, when you add these range requirements to concerns about range and charger anxiety, this requirement of up to 400 or more miles of range is nonnegotiable. (That said, as education and awareness grows I suspect an increasing number of consumers will find that 250 or so miles of range is perfectly acceptable). And the good news, as the above EV Adoption chart shows, in just 2-3 more years, the average range of BEVs available in the US will be close to 300 miles. And many higher end models from Tesla, Lucid, GMC, Rivian, and others will approach 400 or more miles.

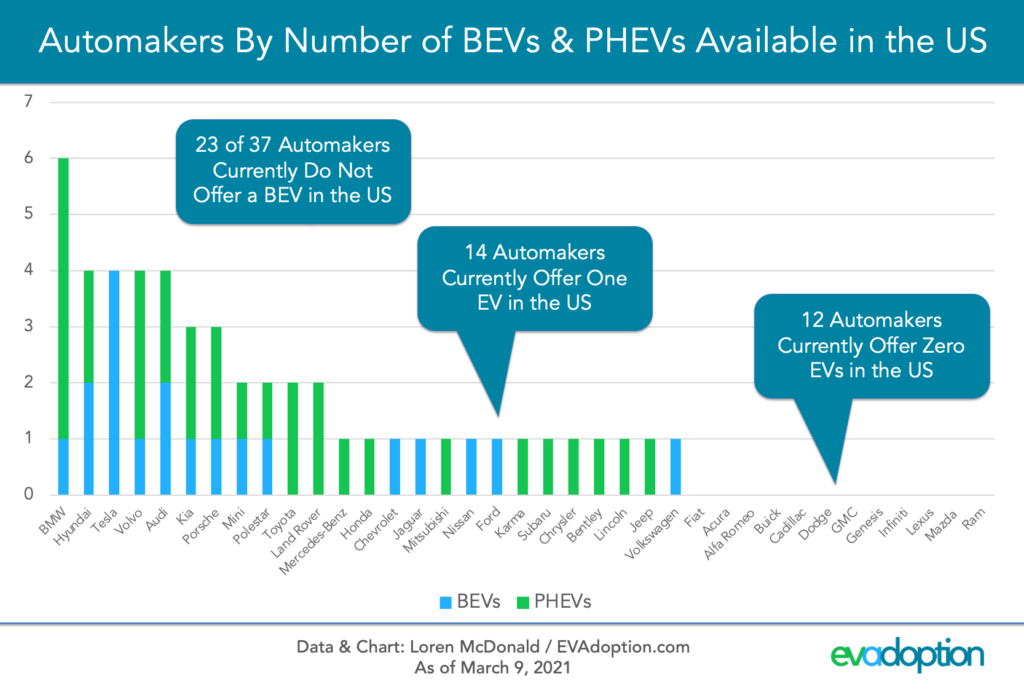

M = Model Availability: One of the biggest hurdles to EV adoption in the US is simply a lack of compelling and affordable EVs across all brands and segments. And we are still several years away from that point as we lack electric pickups (several coming in the next 18 months), EVs under $25,000, and many brands offer zero or only one EV.

After 11 years of the modern era of electric vehicles that began in 2010 with the Nissan LEAF and Chevrolet Volt, we still don’t have a single BEV or PHEV pickup available in the US. Fortunately that is about to change with half-a-dozen on the way in the next few years. In particular, if the electric version of the Ford F150 is compelling and not too much more expensive than a loaded gas version, it could be a strong seller.

In addition to trucks, SUVs, and more affordable EVs – American consumers need more choice. If you walk into an auto dealer (of virtually any brand) located outside of the West Coast, chances are good that there will be zero or perhaps only one EV model available from the brand(s) that dealer represents.

In fact, currently in the US, 12 auto brands do not offer a single electric vehicle (BEV or PHEV) and 23 of 37 brands do not offer a single BEV.

By the end of 2022, only 3-4 more brands – GMC and Cadillac for certain, and possibly Lexus and Mazda will offer an EV in the US. That would still leave eight automakers without an EV.

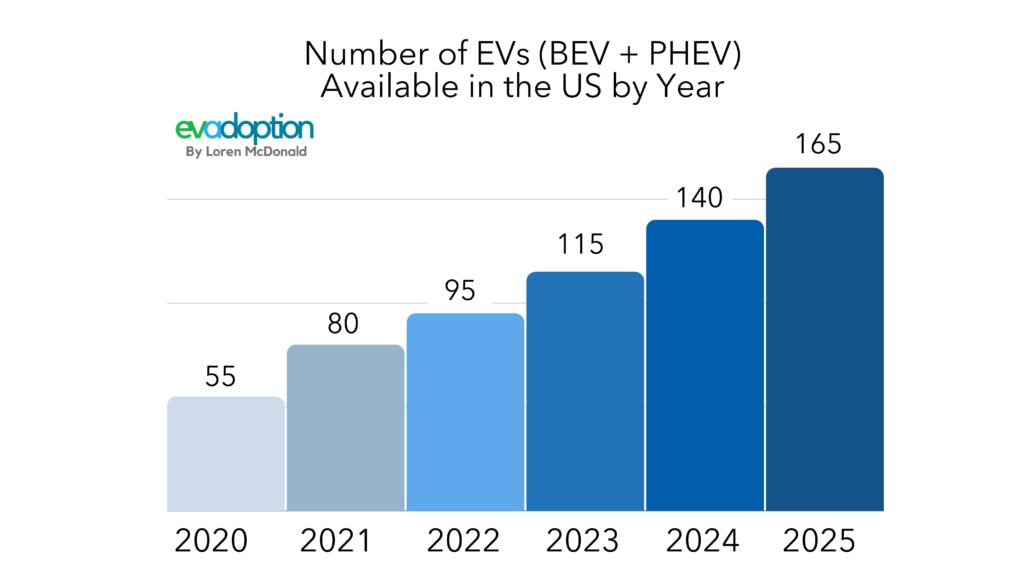

Almost every week now, however, we learn of a new EV that is expected to be available in the US in the next 1 to 3 or so years. With new model plans constantly in flux and many EVs being delayed, it is difficult to be precise on the number of EVs that will likely be available per year now through 2025. That said, my tracking of future expected models suggests that the number of EVs (BEV and PHEV) available in the US should triple by 2025 from the number available in 2020.

A = Awareness: Along with model availability comes actual awareness and understanding of EVs and PHEVs. In some Northern California communities, for example, there is literally a Tesla on every block, while in many parts of the US, consumers have never even seen a Tesla and couldn’t tell you want the acronym “EV” stands for.

There remains a basic lack of understanding about EVs. Several surveys have revealed that many consumers believe that EVs like those form Tesla still have a gas engine. It is likely that their perception of an electric vehicle stems from being aware of the popular Toyota Prius hybrid. I recall a few years ago at a Thanksgiving family get-together, my niece referred to our Tesla Model S as a hybrid. She looked puzzled when I explained that there was no gas engine.

But beyond confusion about the powertrains, refueling is the biggest area that requires education. Until you’ve owned and driven an EV for at least a few months and driven on a couple of road trips, it’s hard to truly understand the nuances of EV charging.

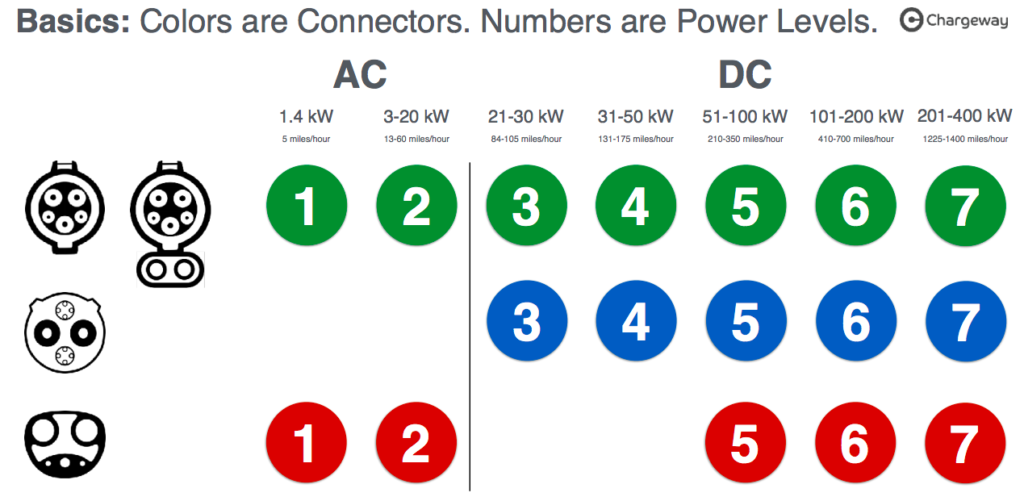

As my friend Matt Teske, CEO and founder of Chargeway points out, we need to change the language we use about charging and educate consumers about electric refueling. In other words, one of the biggest keys to electric vehicle adoption is to get the average consumer to understand that charging is simply refueling your vehicle with electricity instead of gasoline.

Consumers understand gas terms like Regular, Mid-Grade, and Supreme – but charging terminology such as DCFC 150 kW or CHAdeMO connector 240V Level 2 makes their eyes glaze over. This is why I love what Chargeway is doing, by simplifying for consumers the combination of connectors (color) and charging speed (numbers).

Lower battery prices and electric vehicles reaching price parity will be key enablers to driving mass adoption of EVs in the US. But battery and model supply along with ubiquitous charging and consumer comfort with electric refueling are bigger factors that will limit growth in EV sales in the US in the near term.

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

7 Responses

In my opinion battery quality lithium carbonate / hydroxide are much of an issue than battery cells. You can build a new battery cell plant in 18 months but a new lithium project takes at least 5 years. All industry experts predict a structural deficit of supply. (see also my battery quality lithium demand estimate for 2021) The question is when the gap is really widening and how big it will become. Lithium prices have been increasing extremely fast for the last months and there is no end in sight. On the other side their agressive targets for the number and size of new battery cell factories.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1tUYfLuzui3ygxZpPFvCX9zr1liI47_3c6Cl3j_PGNQg/edit?usp=sharing

(also includes a table from S%P Global intelligence that shows 706 GWh of annual battery cell production capacity in 2021 globally)

here is the lithium ion battery megafactory pipeline from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence

https://www.benchmarkminerals.com/ (“battery cell” tab)

Loren, I think you are missing one more core challenge and that would be Ritual Anxiety. If I have an EV what excuse do I now give to my spouse so I can go have a cigarette? Where do I go to buy my night crawlers to go fishing? I have this urge for a bag of chips, so I think I will top off the tank and pick up a candy bar. How many EV charging stations have a bathroom? Some teenagers at one time left their house just to hang out at the Gas & Sip on a Saturday night (Those people are over 50 now). EV charging is currently a very boring event. I personally hate going to gas station, as I love charging up at my house. But for many people going to the gas stations allows America to pick up some Skoal and a bottle of coke, where eventually I can spit my Skoal. Or maybe I want a quick burritos or hot dog without mama knowing. Anyway, this gas station ritual is going to be hard to break. Two Cents

Great point Mike. And I agree, the current state of EV charging locations is pretty abysmal. Many don’t have restrooms, or air pumps for tires, or even a squeegee for cleaning your windshield, let alone convenience store-like items (Big Gulp, cigs, beer, candy bar, etc). But we are eventually going to see that change with the convenience stores I believe adding DC fast chargers and adding more quick-service food options so that people park, charge and eat a sandwich, burger, or burrito for 30 mins and add 200 miles of range. We will get there and then you can say you are going out to get your night crawlers and some “juice.”

One key component missing is advancements in motor technology. There a

Is at least one motor advancement poised to impact all EVs that doubles the range for the same battery power supply. Thus, 1/2 the batteries (less weight and cost) would produce the same range as current models. I have been working to bring this advancement to market and pending launch will indeed accelerate the adoption rate, profitability potential for OEMs, decrease demand (short term) for commodities, increase consumer awareness and decrease reluctance at the same time. Happy to discuss further if you want to learn more, eliminate skepticism, and break the story.

Clifton, thanks for the comment. The article ended up much longer than I originally planned and in the end I had to leave out a lot of things or it would have turned into a mini book. Not sure of you advancement, but in the battery area, I am quite bullish on solid state batteries when they come to market and are powering EVs probably around 2026-2027. I expect range to increase 50% initially and eventually 100% which means OEMs can use smaller battery packs (less weight, lower cost) to provide say 300-350 miles of range – which combined with super fast charging should satisfy 90%+ of the US market.

Lincoln PHEV: Aviator and Corsair

https://www.lincoln.com/hybrid-electric-vehicles/

The Lincoln Aviator PHEV is about $12,000 more than a similar gas version. And Lincoln does not even promote that it is available for various incentives, including $6,843 federal tax credit.