One of the comments you often hear from legacy automakers and the anti-electric vehicle camp is that “consumers don’t want EVs.”

“There are no customer requests for BEVs. None. There are regulator requests for BEVs, but no customer requests.” – Klaus Frölich, via Forbes

These electric vehicle “nega-Bobs” will usually tout that either only 1% or 2% of vehicles purchased in the US (or elsewhere) are electric. Yes, EV sales are still a small percentage of overall vehicle sales, but it is important to look much deeper at what’s driving the current state of EV adoption. A major omission in these statements around the lack of consumer demand is the point in time we are at in the EV adoption cycle. And add in multiple supply factors and it puts the consumer demand question in an entirely different light..

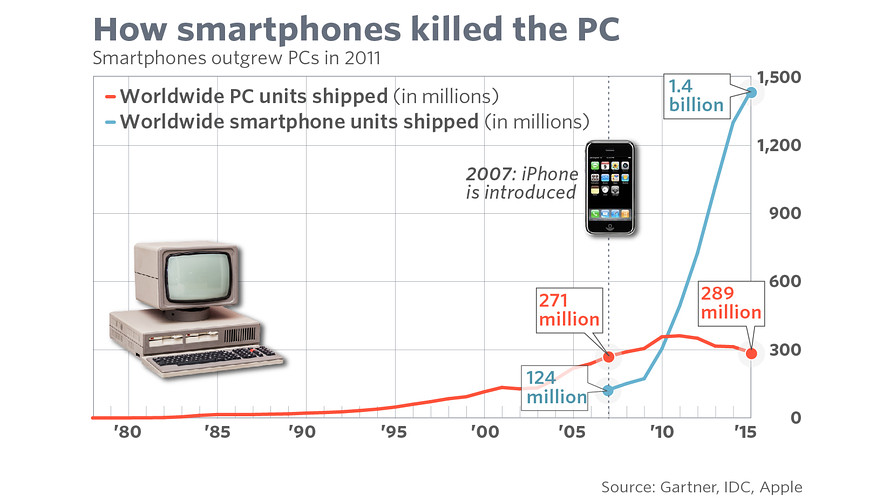

Electric Vehicles Are NOT (Yet) Analogous to Smartphones

Saying that consumers don’t want EVs is a bit like saying in 2005 that consumers don’t want smartphones. The choices and price of smartphones were very limited at that point to devices such as the Palm Treo (of which I owned and still have the one at the right sitting in a drawer) and Blackberry. When the iPhone and multiple Android smartphones became available, the huge increase in functionality with mobile apps made these devices immediately apparent to consumers that they were a huge leap beyond what regular cell phones could do. Within a few years of these new devices coming to market, sales of smartphones took off.

Current electric vehicles simply don’t offer all of the improved benefits over internal combustion engine-powered vehicles like smartphones provided versus landline and cell phones. One, and many EV advocates do, could make the argument that the Tesla Model 3 is analogous to the Apple iPhone, but I believe it may be more akin to a device like the Palm Treo. The Model 3 might be comparable to the iPhone from a technology perspective, but its sales impact – as significant as it is – is still relatively small. The Model Y might change this, but ultimately it may take an EV from a legacy automaker like Ford or Toyota to create the “iPhone effect.”

Supply Issues Are the Root of the Demand-Side Issue

There are several factors on the demand side that in fact are limiting American consumers’ appetite to buy electric vehicles. These include:

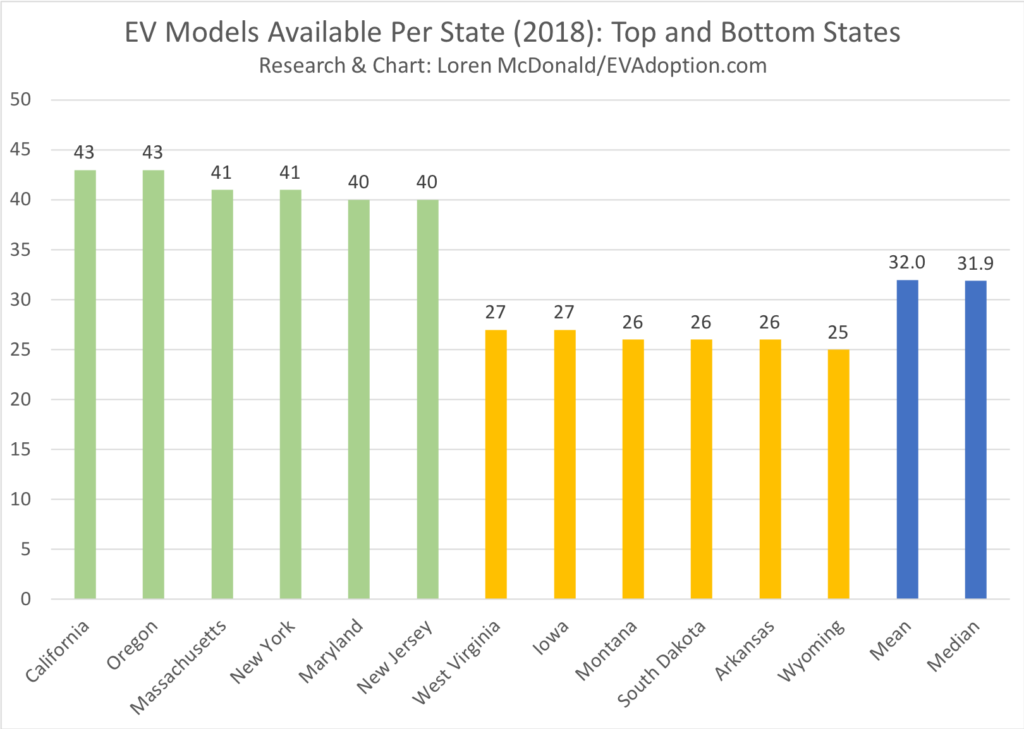

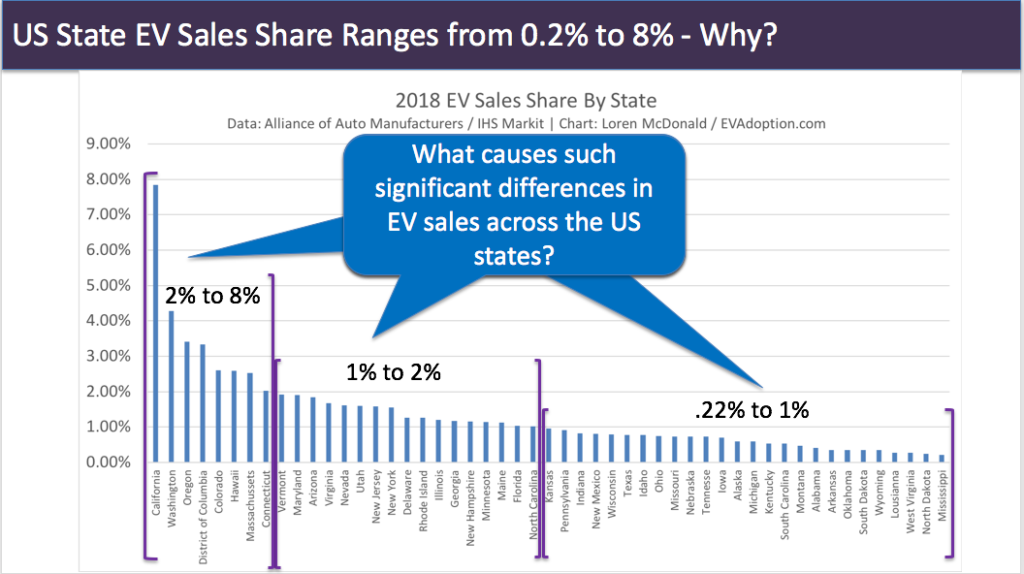

Availability by State: If electric vehicles are not available at dealers across the US, it is pretty difficult for consumers to buy them. As such, it is no coincidence that the states with the most EV models available in their states, also tend to have the highest sales shares for EVs. Conversely, states with the fewest EVs available have the lowest EV sales share. Now, much of this is due to demographics and psychographics of residents of these states, but it is clear that automakers de-emphasize EVs in many states, contributing to very low sales in those states.

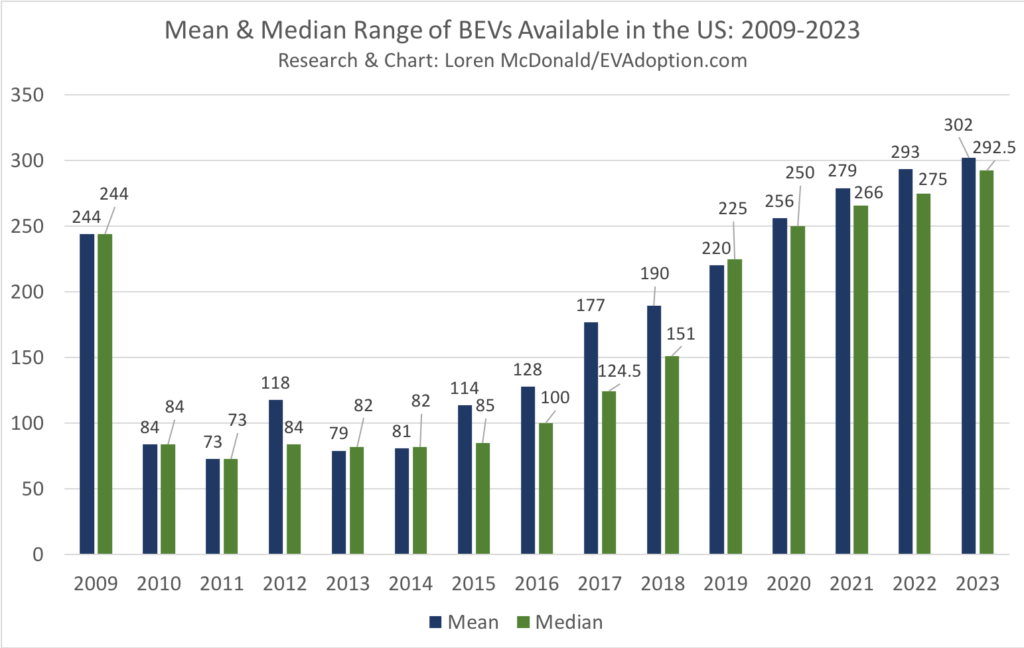

Range: For consumers even remotely considering an electric vehicle, range is most likely the first consideration hurdle before they get to price and other factors. For most US consumers, 250-300 miles of range is the minimally acceptable starting point. But in fact 300-400 miles of range will be required for mass adoption and particularly the late majority and laggard consumers in the US. By the end of 2019, however, the available BEVs will have a median range of only an estimated 225 miles.

But by 2023 I expect BEVs available in the US to have a mean range of 300 miles, which will begin to significantly reduce the fear of range anxiety and make EVs much more acceptable to the mass market.

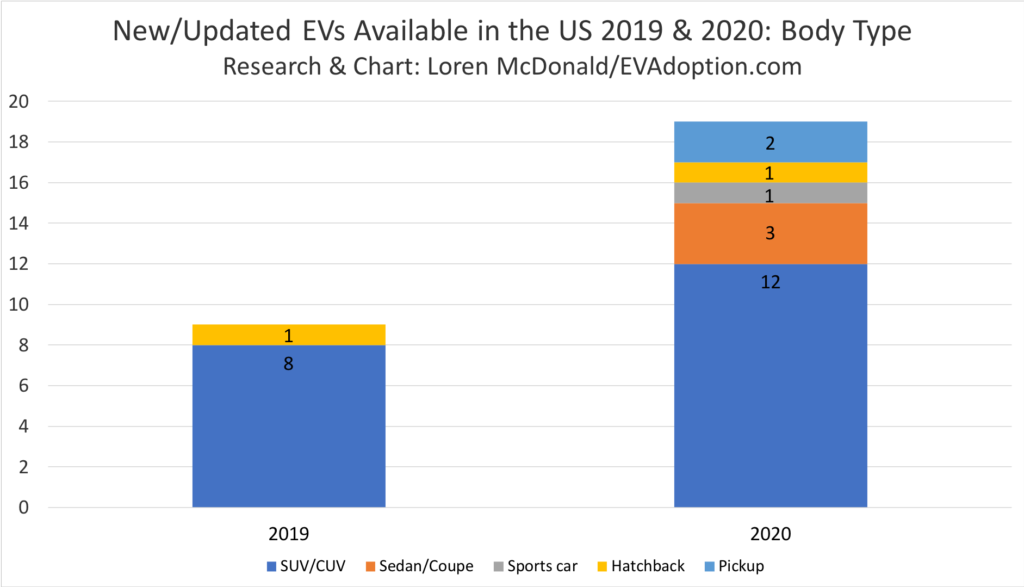

Body Types: One of the current issues is simply a mismatch between US consumer demand and EV vehicle body types. For one, there currently is not a single electric pickup truck available. Pickups accounted for 17% of US vehicle sales in 2018, using data from GoodCarBadCar.

Secondly, small SUV/CUVs are the hottest segment today in the US. In 2018 the Toyota RAV-4 ranked as the number 4 selling vehicle in the US, the Nissan Rogue/Rogue Sport was the number 5 best-selling, followed by the Honda CR-V. The Chevrolet Equinox crossover came in at #8, and Ford Escape at #12.

Fortunately, in the next few years we will see electric pickups from Rivian, Tesla and Ford reach the US market. Though these BEV pickups will likely be priced significantly higher than the typical pickup which will limit sales to higher-income and early adopting households. Additionally, BEV crossovers such as the Tesla Model Y, Volkswagen I.D. CROZZ, and “Mustang-inspired” Ford CUV along with the Ford Escape PHEV should sell well.

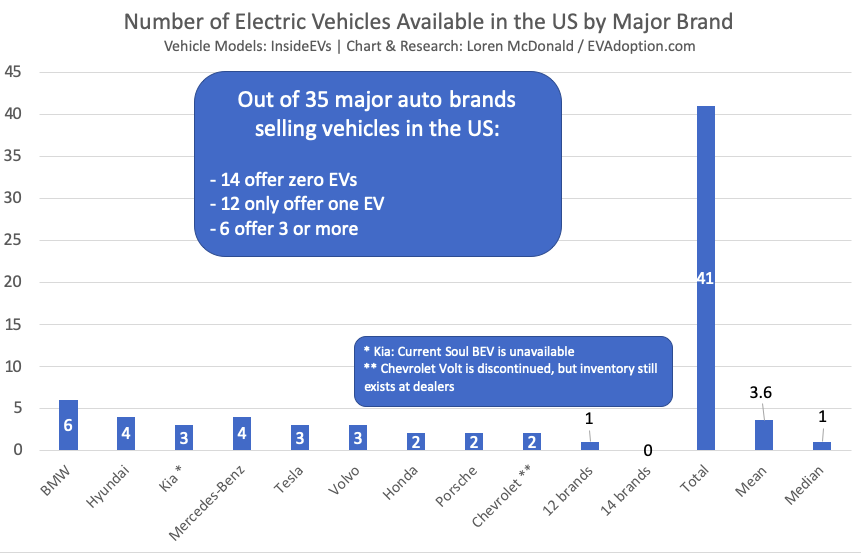

Number of Models: According to Statista, as of July 30, 2019 there were 293 models available for sale in the US. At the same time there were 41 EVs available – 15 BEVs and 26 PHEVs – or 14% of total available models. However these numbers are skewed as BMW offers 6 EVs, Hyundai and Mercedes-Benz 4, and Tesla, Kia, and Volvo have 3 EVs available in the US.

Automaker BEVs PHEVs Total

BMW 1 5 6

Hyundai 2 2 4

Kia 1 2 3

Mercedes-Benz 0 1 1

Tesla 4 0 4

Volvo 1 3 4

Honda 0 1 1

Porsche 1 2 3

Chevrolet 1 0 1

Audi 2 2 4

Fiat 0 0 0

Ford 1 0 1

Jaguar 1 0 1

Mini 1 1 2

Mitsubishi 0 1 1

Nissan 1 0 1

Karma 0 1 1

Polestar 1 1 2

Subaru 0 1 1

Toyota 0 2 2

Volkswagen 1 0 1

Chrysler 0 1 1

Bentley 0 1 1

Acura 0 0 0

Alfa Romeo 0 0 0

Buick 0 0 0

Cadillac 0 0 0

Dodge 0 0 0

GMC 0 0 0

Genesis 0 0 0

Infiniti 0 0 0

Jeep 0 1 1

Land Rover 0 2 2

Lexus 0 0 0

Lincoln 0 1 1

Mazda 0 0 0

Ram 0 0 0

Total 17 34 51

(Note: The existing Kia Soul is not currently available but the new version will be soon. And the Chevrolet Volt has been discontinued, but dealers are still selling existing inventory so is included.)

The implications are that when a consumer walks into a car dealership in the US, only 21 out of 35 major brands will offer at least one EV out of their total portfolio of models. Twelve brands offer only a single EV. And in a majority of states, various brand dealers may not even offer EVs that are available at dealers in states like California and other ZEV states.

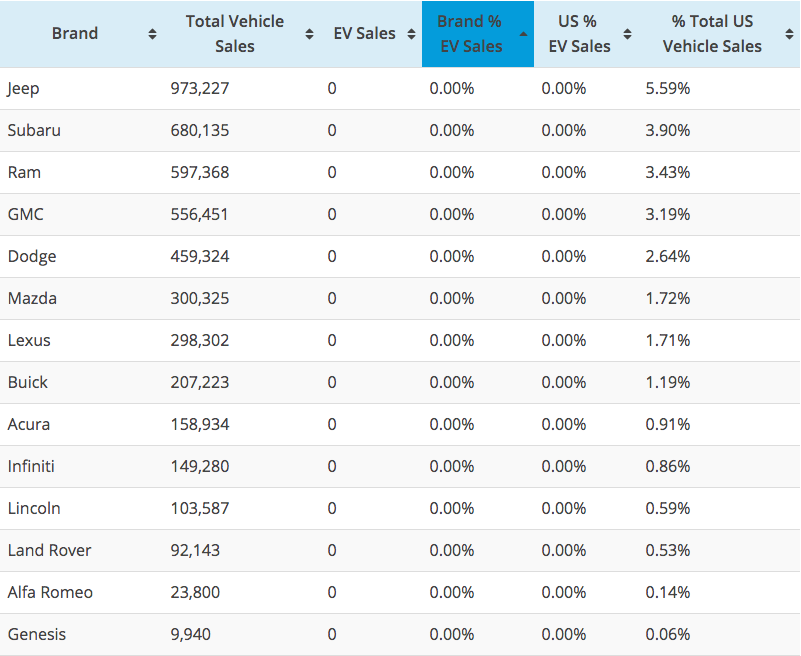

Many Automakers Simply Don’t Offer EVs: In 2018, 14 automaker brands had zero sales of electric vehicles in the US. This wasn’t because of a lack of demand by consumers, but because these 14 automakers didn’t offer a single EV for sale.

Currently, in the US, out of 35 major brands, the number of brands without an EV remains at 14 with Subaru launching its Crosstrek PHEV, but Cadillac discontinuing the CT-6 PHEV. (Lincoln and Land Rover are launching PHEVs in the next few months.)

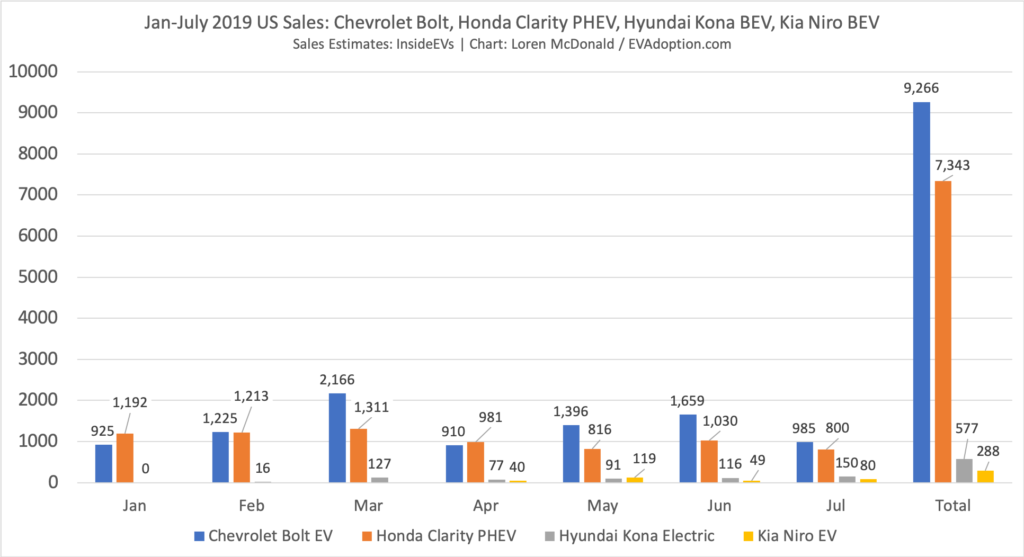

Low Supply of Models: Highly-rated CUVs like the Hyundai Kona and Kia Niro BEVs are not widely available. These automakers either planned poorly and didn’t secure adequate battery supply or they intentionally are keep availability low. These two models should be selling in the same range, or likely even higher than the Chevrolet Bolt.

Further, Honda recently pulled back availability of the hot-selling Clarity PHEV to ensure adequate supply for dealers in California.

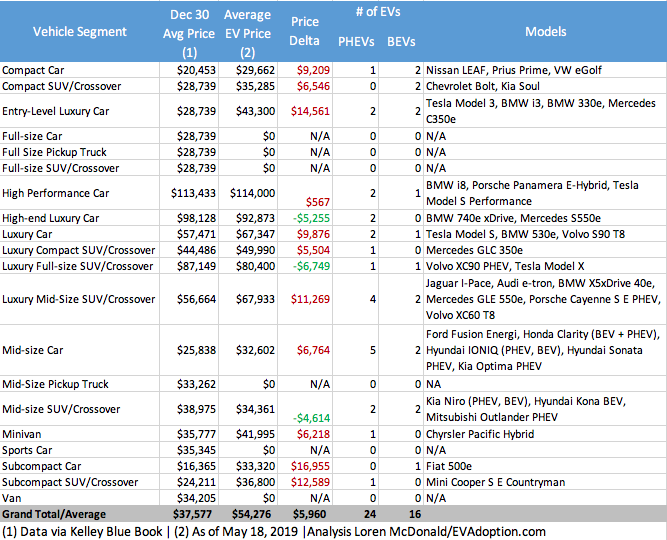

Price Differential: EVs cost $17,000 more than the overall average of all vehicles. More telling, however, is the price differential (delta) across most of the vehicle type categories. On average EVs cost just under $6,000 more than ICE vehicles in my analysis – but well above $10,000 more in several categories.

While there were only two EVs in each of two categories – High-end Luxury Car and Luxury Full-size SUV/Crossover – that EVs actually cost less on average. Again, not a big surprise but interesting to note that the more expensive EVs also tend to be more competitive. This likely speaks to part of the reason why Tesla’s Model S and X have historically sold well. While both are very expensive vehicles, they are actually very competitively priced within their categories.

Manufacturing Cost Differential – EVs Are Sold at a Loss: The biggest supply issue is simple – electric vehicles cost more to produce and most all EVs today are sold at a loss. Automakers are in the business to make a profit, so their only motivations currently to sell EVs are to 1) Meet government regulations around emissions and average miles per gallon in key markets like China, the EU and California; 2) Build supply, design, and manufacturing competencies in preparation for when EVs are competitive with ICE vehicles on price and range; and 3) Counteract electric vehicle competitors such as Tesla and the German automakers who are launching several luxury/performance EVs.

According to an article in GreenCarReports, consulting firm AlixPartners “pegs the cost of building new electric cars at almost $9,000 more than conventional cars, and plug-in hybrids at an additional $5,700.” In this McKinsey report, the management consulting firm says that there is currently a $12,000 difference in cost between a typical BEV and ICE.

An article in Electrek quotes GM’s CEO Mary Barra from a company earnings conference call commenting on the profitability of EVs:

“I would say early next decade, but I wouldn’t put any more specificity on EV profitability than that. We’ve talked about the fact that with our next generation of development, we want to make sure we have obtainable, profitable, desirable, and with the appropriate range. And so that is the work that we’re doing.” – Mary Barra, CEO of GM

In the end, getting electric vehicles to become profitable for automakers is the key issue to drive supply, which in turn will lead to a huge uptick in demand by consumers.

California is a Leading Indicator in the US

In California electric vehicles are in very high demand, with current sales market share running at just under 8%. The state’s perennial high cost of gas, the lowest percentage of pickup owners, culture of environmental concerns and high solar installations, and number of higher-income households in Los Angeles, San Jose and San Francisco markets are some of the key drivers of EV adoption.

The Tesla Model 3 has been an ideal match for these factors and in the first half of 2019 it was the third-highest selling vehicle in the state behind the Honda Civic and Toyota Camry, according to the California New Cars Dealers Association.

This simply proves that when an electric vehicle is widely available and meets the needs of consumers within a market, there simply is not a demand issue. Once the factors above are resolved and available EVs are actually more in line with the needs of the market (and profitable for automakers), sales will begin to take off. Consumers want electric vehicles, just not most of the ones currently available, many of which are in fact not widely available.

10 Responses

Another excellent article. Thanks!

IMO, the other thing that needs to happen to enable BEV sales is to get sufficient fast charging stations in more states/communities. There are exactly 0 where I live (unless you count Level-2, in which case there are 6 in our town of 50,000 people). So I drive a PHEV. Seems like the BEV/PHEV battle, and EV adoption in general, will be ultimately decided on how fast the charge station buildouts accelerate. Range anxiety to allow for BEVs can only be mitigated when ubiquitous charging is available, as it is in California.

BTW – Please check the colors in the table of body types. I think SUVs and Sedans are reversed.

so all we need is to get the rest of the country to artificially drive up the price of gasoline, browbeat people into disliking pick-ups and SUVs, reeducate the populace to hate industrial progress as much as the folks in California do and mint a few more millions of dot.com, FB and government bureaucrat millionaires and then we’ll solve the demand problem right?

Hi Loren,

Great article! Love the way you dispel the myth that all EVs are more expensive by splitting into vehicle segments.

It’d also be interesting to see this same chart with total cost of ownership (factoring in not just sticker price, but also fuel and maintenance savings).

Another factor that should be considered in cost of ownership is the fact that Tesla batteries are now lasting for 400,000 miles (and a 1 million mile battery is in the works).

Finally, can you please correct the Vehicle Segments chart by changing the color on the mid-size crossover SUV from red to green? I’d like to share. Thanks!

Thanks Janelle … I will correct that mistake sometime today … thanks for pointing it out!

That chart is now fixed Janelle.

I think the grand total/average delta may be incorrect.

So consumers don’t like the EVs that exist, they’re roughly 10 grand more expensive, the range is poor, they can’t be made profitably, and the government has to bribe people to buy them.

I don’t know, man. That sounds a lot like a demand issue. And a demand issue that isn’t likely to improve with a few years of rock-bottom oil prices ahead. EVs always have been a niche market, and it looks like they will continue to be so for the foreseeable future.

I mean really, what happens when I drive 200 miles and my battery dies? In my ICE, I just put more gas in the tank and drive. With an EV, I have to hope to find a charger and then wait for it to charge. It’s really a pain when I just want to drive across the state to visit family.

Hi evadoption,

It seems obvious that massive changes to the power grid will be necessary to allay range anxiety. But, what is rarely asked is, does this make any sense? If, overnight, 10% of the cars on the road became EV’s, the grid would likely crash across the country. Almost inconceivable increases in capacity, at the production and consumption end, would be needed. Where is this going to come from? To many environmentalists, nuclear is off the table, leaving fossil fuels as the only viable option. What will be the impact of this? Additionally, a redundant, nationwide network of fast charging stations will be needed to provide EV’s with even a fraction of the convenience and versatility of ICE’s. A move to EV’s will likely have more negative impact on the environment than that of improving modern, efficient, ICE’s; and far more impact than a conceivable future where sensible, plug ins like the Volt dominate the family/commuter car market. Such vehicles eliminate range anxiety and require no massive changes to the infrastructure, other than a gradual increase in capacity; no residential fast chargers, no urban charging stations, no nationwide network, etc… All of which will impose a huge impact on the environment.

Given that the daily driving needs of most drivers are met by the range of a Volt, why carry around a huge, environmentally toxic battery that produces significant harm, provides no benefit at all the vast majority of the time, adds a lot of unnecessary weight, and is still crippled compared to an ICE in terms of range and convenience? Pure EV’s make no practical or environmental sense. EV’s are not zero emission vehicles, they are remote emission vehicles and, much of the time, coal powered vehicles. Given that EV’s still produce emissions, why the obsession among the EV community with the tiny amount of emissions produced by a car like the Volt? Again, the changes needed to power all of these EV’s will be massive and impose a huge environmental burden.

If one is concerned about the environment, why the push for pure EV’s over far more sensible plug in hybrids? Such a vehicle has all of the advantages of a pure EV most of the time, with none of the drawbacks, both in terms of convenience and environmental impact. The production and disposal of batteries is very harmful. Plug-ins don’t need big batteries, or the additional infrastructure to power them. In addition, it is likely that battery life could be significantly longer with a plug-in than a pure EV because they don’t need to maximize range, which, with a pure EV, must come at the expense of optimal battery management and environmental impact. The Volt battery cannot go into deep discharge and doesn’t need fast charging (the two most significant factors in battery degradation), thus is likely to last far longer than the huge batteries needed for long range pure EV’s. Smaller battery, longer life – better for the environment.

The solution to range anxiety already exists, no extreme changes to the infrastructure, no massive tax subsidies, often channeled to politically connected corporations, needed. EV’s will never be able to compete on range and “fueling time” with ICE’s. ICE’s will never be able to compete with EV’s in terms of convenience for the majority of daily driving needs. Right now, plug-ins suffer from neither constraint and, considering what is needed for mass adoption of long range EV’s, are almost certainly better for the environment.

Kind Regards,

Jeremy

Jeremy, thanks for the detailed comment. While I don’t agree with some of the nuances of your point (grid impact, coal power – EV adoption is happening mostly in non-caol states and the grid is getting greener faster than EV adoption, batteries are and will be recycled into home/grid storage, EVs once solid state batteries late this decade are commercialized will easily compete on price and range with ICE powertrains, etc) – I DO agree that PHEVs at minimum are a great near-term solution and transition to full BEVs this decade.

Obviously the Chevrolet Volt was the poster-child PHEV with its 53 miles of range, but was discontinued in 2019. The current challenge with PHEVs is that there are very few with more than 30 miles of range. For a PHEV to do everything you suggest – like with the Volt – we need a number of PHEVs with at least 40-50 miles of range. The Toyota RAV4 Prime and Ford Escape PHEV both with around 40 miles of range are coming to the US later this year – but Toyota is only making 5,000 units.

Which gets us back to the topic of this article that you commented on – supply. And so while I agree that PHEVs make a lot of sense and solve several shortcomings of BEVs for consumers – there simply aren’t many capable PHEVs currently available. But good news, there are a few coming … but will be interesting if we see more high-range PHEVs arrive in the next 2-3 years.

Hi evadoption,

Thanks for the reply, I appreciate it. I’d like to go through your points and get your feedback.

“While I don’t agree with some of the nuances of your point (grid impact, coal power – EV adoption is happening mostly in non-coal states and the grid is getting greener faster than EV adoption”.

A greener grid can power a relatively small increase in BEV’s, but what about mass scale EV adoption? Wind and solar can’t, which leaves coal, natural gas or nuclear. The only viable “green” technology here is nuclear, which many environmentalists reject.

“…once solid state batteries late this decade are commercialized will easily compete on price and range with ICE powertrains.”

Perhaps, but they will never be able to compete on fueling time which, even if the supply problem of a currently inadequate nationwide network of charging stations is solved, will matter a lot to the “demand” side of the equation.

“I DO agree that PHEVs at minimum are a great near-term solution and transition to full BEVs this decade”.

OK, here’s the crux of my problem, it seems to be an assumption in the EV community that full BEV’s are obviously “better” for the environment than PHEV’s. This assumption only makes sense if one isolates this point in time, how this BEV compares to this PHEV or ICE, right now. But, as your site name indicates, EV advocates want mass adoption. Again, from where is the power required for this going to come? What about the environmental impact of building all of this new infrastructure? An honest examination of the environmental impact of what will be required for mass adoption of BEV’s is needed. A big part of the supply problem you highlight is the fact that the infrastructure to adequately support wide scale adoption of EV’s does not exist. It is possible that, if this infrastructure is created, at taxpayer expense, and absent current market demand, that more people will buy BEV’s, but this will be artificially created demand.

Some thoughts:

– BEV’s are ideally suited for the daily commuting needs of most in suburban environments.

– ICE’s are ideally suited for the needs of most long distance, rural or urban drivers.

– PHEV’s suit them all.

Sure, I get, from a marketing perspective, range is emphasized. But, this represents a failure to market the EV properly. Again, a BEV will never be able to compete on range and fueling time with an ICE. No matter how good battery technology gets, it will always be much cheaper to increase range by adding another gallon or so to the gas tank, 40 – 50 miles of extra range in the tank will always be much lighter and cheaper than the same in a battery.

Yes, the Volt was terminated, and that perhaps lends credence to the idea that BEV’s should be the future. But, bad marketing and high cost probably had something to do with the decision to kill the Volt. Hopefully, more cars like this will become available, and they are not seen as merely “transition” vehicles.

Kind Regards,

Jeremy