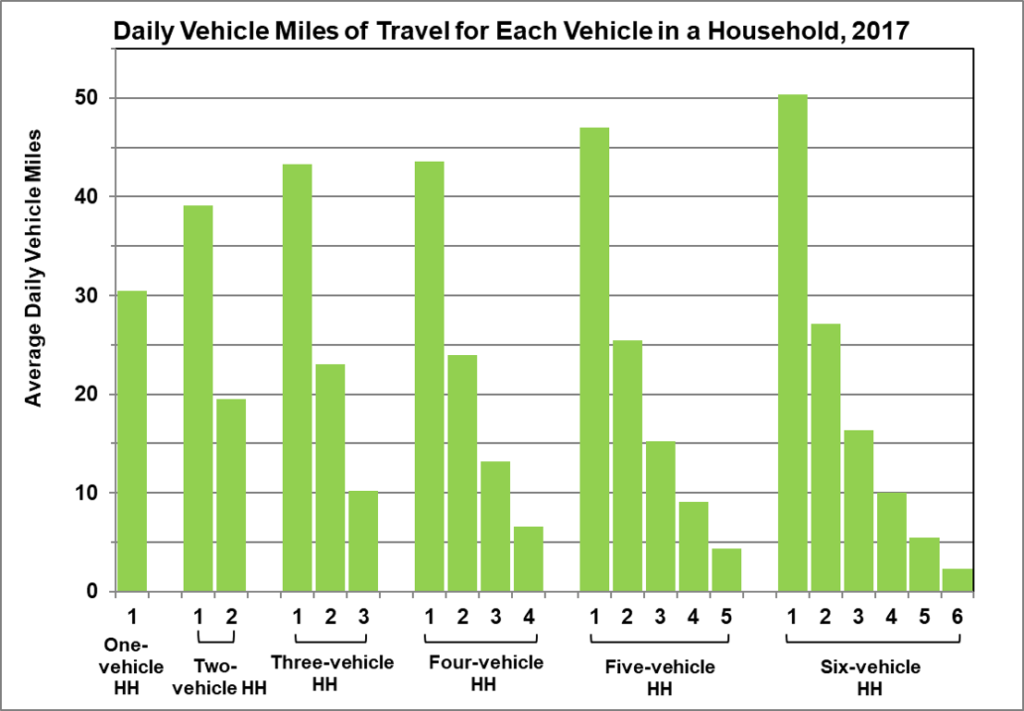

“The average American only drives about 30 miles a day therefore electric vehicles with 150 miles of range is more than enough for anyone.”

I’m sorry, but this logic is utter and complete nonsense.

Excuse me if I come off a bit grumpy but I am sick and tired of electric vehicle advocates who continuously reference some average daily vehicle miles traveled statistic as a reason that American’s don’t need long-range EVs.

The above was a Twitter response to something I posted that is a typical example of incredibly flawed and/or naive thinking. If I had a dollar for every time I have seen a comment on an electric vehicle website, on social media or an article about the average of 30 miles driven each day, I would be a rich person.

“There are three types of lies — lies, damn lies, and statistics.”

― Benjamin Disraeli

The average daily vehicle miles traveled statistic has little to no relevance on the amount of range American consumers want and expect from battery electric vehicles.

What does matter is how the vehicle they own meets their automotive travel needs 100% of the time, which includes the many trips Americans typically take annually that greatly exceed the average daily figures.

One of the other problems with VMT, is the concept of average. Take the following 9 daily trips in miles: 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 35, 50, and 150. These 9 trips range from a low of 3 miles to a high of 150 and total 313 miles. But the average of these trips is 34.8 miles. The 150 mile trip is more than 115 miles longer than the average and hence, average for our purpose of determining BEV range requirements, is simply the wrong statistic to use.

Two Sample Analogies That Show the Ignorance of the VMT Logic

Using average VMT data to base the amount of range consumers need in an EV is analogous to using the average daily temperature where you live to make a decision on the type of clothes you need. Most would agree that would be idiotic.

Let’s look at New York City. The average daily temperature in New York is 55 degrees, but the average low in January is 26 degrees and the average high in July is 85.

Now you might be saying to yourself, “Loren, this is a really stupid analogy.” But is it? Do you buy your clothes for the year based on the average annual temperature, or for the seasons and times of the year when it is mile, cold, and hot? The latter of course.

Now cars are very different from clothes. For one, cars cost a lot more and most of us don’t have a convertible sports car for the summer drives up to the wine country or out to the beach, an AWD SUV for trips to the mountains in the winter, and an efficient sedan for our daily commute to the office.

Now when I say “most of us don’t” in fact a lot of households are two-car households and might own both a sedan and an SUV. But we are likely talking about upper income households and perhaps not your lower- to middle-income families. (Yes, I recognize that those latter families are also not taking weekend ski and wine country trips, but they may be visiting grandma a few hours away in the winter where it snows.)

In fact, most households likely have to buy a primary vehicle that meets most or all of their daily short trip and longer weekend and winter and summer driving needs.

My point of the average temperature and clothing analogy is that as consumers we don’t typically buy very expensive products that solve just some of our needs. Let’s look at another analogy.

Imagine a management consultant who works out of an office most of the time but travels on average twice a month to meet with clients, attend conferences and company meetings. The consultant requests a laptop computer but is told by the IT department that they would only be providing them with a less expensive desktop computer because the employee spent most of the time in the office.

Most of you reading this would presumably agree that this would be a ludicrous response from the IT team as in essence the consultant would be unable to perform his or her job when traveling. (I know some of you might respond that the consultant could borrow a loaner laptop from IT and store all of their documents in the cloud and get by just fine. And well that is theoretically possible, but it would also be incredibly inconvenient and inefficient and would provide additional hardships for the consultant as opposed to just having and using a laptop 100 percent of the time.)

Real-World Typical Trips

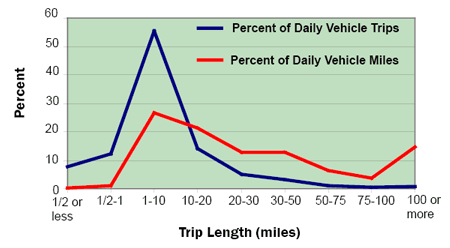

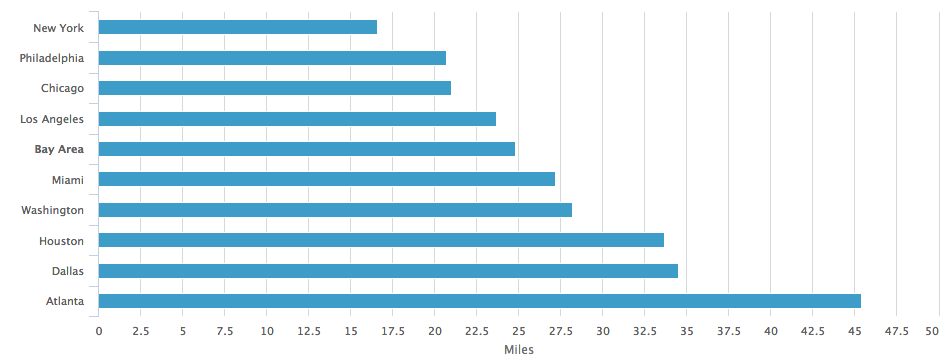

So say a typical household does indeed drive an average of about 30 miles per day. (BTW, in many major US metropolitan markets a typical round trip for many commuters is likely closer to 60-100 miles than 30.) So let’s say that this 30-40 miles per day does indeed account for about 90%-95% of typical trips out of 365 days per year. But what about the other 5%-10% of trips that are much longer?

Following are some examples of the types of these longer than average daily trips:

Visiting friends/family/relatives: How many times per year do you drive to visit friends or family and relatives who might live anywhere from 50 to 500 miles from where you live? The answer obviously can vary widely based on the stage of your life and how far away your relatives live. But for many American’s this might range from at least once per year to 5 or more trips.

Vacation destination: Americans love their vacation road trips. For households with children, there are four common vacation periods per year: spring break, summer, Thanksgiving, and Christmas/New Years. Trips often include driving to visit theme parks such as Disneyland and Disney World, to national parks like Yosemite, to coastal beaches, cities like Las Vegas, Washington D.C. and New York, or mountain areas. Many US households may take one of these vacation road trips per year, or as many as 2 or 3.

Leisure and sporting events: Weekend and day trips are favorite getaways for Americans and these can include day trips to go fishing, attend an auto race, skiing, hunting, or mountain biking. Or they might be a weekend stay over camping or wine-tasting trip. Or these trips might be to a regional soccer, baseball or volleyball tournament located a few hours from your home. Another example, I recently took my wife out to the coast for a birthday lunch and fresh oysters, which was a 160 mile out and back round trip.

My own personal current situation is probably not typical as my daughters don’t live at home now and my parents are no longer living. But several years ago when my parents were alive and both daughters were at home and at least one was active in sports or dancing, our “10%” of trips would include:

- At least one round trip to/from Southern California: about 900-1000 miles round trip

- Several trips up to the mountains to visit my parents: 100 miles each way, 200 miles roundtrip

- 1-3 trips to Reno or Lake Tahoe for volleyball tournaments, dance competitions, camping, skiing: 375-450 miles round trip

- 2-4 trips to the Sonoma/Napa wine country: 100-120 miles round trip

- 1-2 trips to Carmel, Monterey, Santa Cruz area: 150-250 miles round trip

- 2-4 trips to visit friends, see concerts in Silicon Valley: about 100 miles round trip.

For most Americans the vast majority of their vehicle trips are to work, to the supermarket and shopping mall, the doctor and dentist, out for dinner and a movie, and similar local trips. So when people use an average VMT figure of 30 or 40 miles, they are completely ignoring the multiple trips that might be 100 to 500 miles or more that many Americans take each year.

So what many are suggesting when they argue that BEVs with only say 150 miles of range are enough because “we only drive an average of 30-40 miles per day” – is that people should buy a super expensive product that only meets their needs 90%-95% of the time.

Sure people can stop and charge on their way to the mountains or grandma’s house, but when their current vehicle has a range of 400 miles, you are asking most consumers to make a sacrifice, and huge change in behavior that they simply aren’t prepared to make.

Alternatives to Longer-Range BEVs

Some readers may agree with my argument against using VMT to assess range needs for BEVs, but make the argument that this still does not negate that we don’t need long-range BEVs. Some of the alternatives to long-range BEVs then might include:

Fast Charging: Stopping for a short fast charge to ensure you reach your destination or so you don’t have to charge to make it back home. You may argue that this is just a minor inconvenience. And that may in fact be true for early adopters, people who are all in on electric vehicles. But for the majority of consumers you are asking them to accept what they perceive as a much inferior product. Even when standard fast charging can add say 150 miles of range within 10-15 minutes, many consumers will still find this short charging time unacceptable when comparing to the 5 minutes to refuel at a gas station, combined with 400 miles of range..

Destination Charging: A high percentage of the above trips I described are less than 200 miles one way. This means that EV drivers can simply charge when they arrive and their BEV will be fully charged and ready to go for the return trip home. This is true, assuming in fact that there is available destination charging, but also that you may not need your car when you arrive. As destination charging infrastructure gets built out, especially in more remote locations, this alternative becomes more realistic.

Car Sharing/Rental/Subscriptions: One of the potentially promising alternatives to long-range BEVs is the idea of car sharing and subscription services. If your household only takes a few longer trips per year, then renting, car sharing or a subscription service might be just the trick. These options have yet to take hold. But if the subscription model – where you pay one monthly fee that gives you access to more than one type of car – becomes popular, then this approach could be a serious alternative.

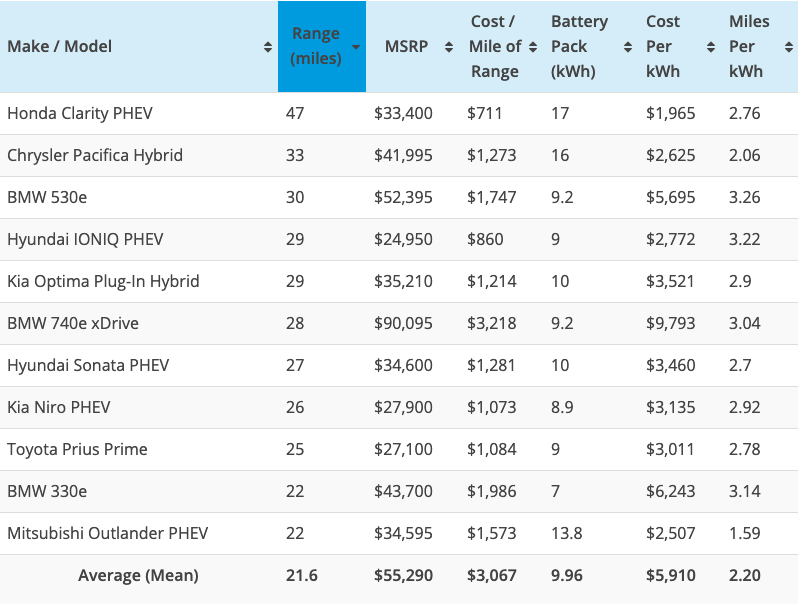

Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles (PHEVs): Perhaps the best alternative is the one sitting right in front of us – the plug-in hybrid. And this is the one area where the daily average VMT actually makes sense. A PHEV with 40-50 miles of electric range might actually meet 90%+ of the driving needs for most Americans. The current challenge, however, is there are only 3 PHEVs available in the US with 30 or more miles of electric range. Until there are dozens of PHEVs with 40-50 miles of electric range, the PHEV is an unfilled promise.

Statistics can be used to support pretty much any argument. But in my opinion, the average of 30~ vehicle miles traveled per day in the US is an over simplistic statistic that fundamentally ignores the non-average trips most Americans take each year. Using this statistic to argue than Americans do not need longer-range BEVs is simply not realistic and a misuse of the average VMT number.

19 Responses

Nice analysis. I’ve been hearing about new EV owners who are not installing L2 in their homes, going instead with L1 because the bigger battery packs mean that they can cover 80+% of their daily drives with overnight charging. Some still complain about range if they have longer daily commutes (Napa to SF), but if they are traveling for personal reasons (sports, concerts family etc.) then stopping for a charge as needed does not seem to be an issue with them.

Thanks John. Stopping for a charge is something that early adopters tend to have no problem with. When they bought their EVs as an early adopter they knew what they were getting into and so stopping for 20 minutes on the way home from Sacramento from a volleyball tournament (or whatever) is not a big deal. You go shopping at the outlet mall, you use the time wisely. But people who are not all in on EVs, the consumers we need for EVs to go mainstream, will expect their cars to go about 400 miles without refueling … and for them that short stop for charging just means that EVs aren’t yet as good as gas cars.

I’m re-analyzing the need to buy for my most extreme needs, i.e. I have a 2013 hybrid 4×4 Pathfinder that has done me a solid in Mammoth and Tahoe but that’s literally four times in the last six years. I could rent a vehicle that satisfied those needs. If I can get an EV that satisfies 95% of your travel, is it an imposition to access Turo or a daily rental to satisfy the 5%? And how many of those folks are in two-vehicle households in which the second car satisfies that 5%? To your point, I think PHEVs split the difference pretty well, even though they’ll be on ICE for part of the time, and their residual values are stronger than EVs. But bringing the two to three times a year an American family goes on vacation into an EV equation today is a red herring argument. EV buyers aren’t “completely ignoring those trips,” they have alternative arrangements that work for them.

Chris, I think the magic word is “could.” Most Americans are first and foremost focused on convenience. Yes, 2-car households can use their big gas guzzling SUV to drive to Disneyland, and their Nissan LEAF to work and school, etc. That is much of the current market of early adopters.

And renting a car for a trip? We are used to renting cars when we reach our destination after flying, but how many Americans will make the switch to renting for a long drive? What are the mileage costs for driving a rental car 500-1000 miles?

Again, early adopters might do these things … but the mass consumer market just expects their car to go about 400 miles before needing to be refueled and then it only takes a few minutes to refuel. The former will be easier to reach than the latter, which will require a lot of education and better road-trip charging experiences. But it isn’t just about the long road trips – it is the 150-200 mile trips we take to the beach for the day or to visit grandma, or whatever … we will get there, but it is going to take longer range EVs, faster charging and education of drivers of the difference in charging while you eat versus stopping to refuel.

But we completely agree, I think PHEVs could be the ly to mass EV adoption and a bridge to people buying 100% BEVs in 15 years or so.

Sure, I think we just differ slightly on changing the mindset of the average consumer. It’ll be interesting to revisit this conversation in four or five years, in light of infrastructure buildout and battery improvements.

Yes, 5 years from now the market will be very different …. 40 or so more EV models available in the US, more model types, lower battery costs, more education, more informed dealers, more serious automakers, greater charging infrastructure buildout … but gas prices will be a key wildcard.

I replaced my ICE powered vehicle with a BEV just a few months ago, and had a 240v EVSE installed at my residence. As Chris points out, the deciding factor of me was the BEVs ability to get me to my furthest routine driving points and back home without the need for charging elsewhere, in the most extreme temperature conditions for this region (Mid-Atlantic). The “convenience” factor here is having sufficient KW/h to run my A/C or heater as need be to stay confortable while making these trips. My main focus, however, was and is cost-effectiveness and TOC.

You are absolutely correct concerning the need for educating drivers — particularly on the financials of BEV vs ICE operation. After all, ICE powered vehicles have been the only game in town for many decades and most people (at least those I know, anyway) are firmly rooted in an ICE vehicle paradigm. In “evangelizing” to neighbors and others who’ve approached me with questions, I always focus on the amount of money required to operate my BEV vs what it was costing me to run and maintain my old ICE car — to do the same thing as my daily driver. I encourage them to “do the math” associated with their own circumstances and project their potiential savings over time.

An EV that satisfies 95% of one’s driving needs can save the owner or lessee some serious bucks over an extended period. How then do the savings compare with the cost of meeting the remaining 5% by alternative means? Since mine is a 2-car household, we have the options of using my spouse’s ICE-powered mid-sized sedan, rental, fly & rent (outside of vacations), or Amtrak (business related). Of these, the cheapest effective alternative is the one that’s selected, and for us anything beyond an occasional 300 mile to 400 mile trip in her car is so infrequent that the cumulative savings from my BEV use are minimally reduced by resorting to one of these alternatives. I suspect that most folks would similarly find that doing so is not really a financial imposition in light of the residual savings, as Chris has suggested.

As for PHEVs, the 30 mile average trip figure may indeed be a valid thumbnail for their selection. In my view a really useful PHEV should be able to make this trip in electic mode in the most demanding weather conditions. Given this requirement a 50-mile range capability is in order; currently such a vehicle is currently unavailable outside of California, if I’m not mistaken. Futhermore, since PHEVs have elements of ICE drivetrains it stands to reason that their maintenance requirements and TOC would be substantially higher than that of BEVs, does it not? In any event, they too have their place and when my spouse’s ICE reaches the end of it’s useful life our plan is to replace it with a 50-mile range PHEV, depending on what’s available at the time.

Thorris, thanks for the detailed comment. And yes, as you point out weather conditions are a key concern for buyers, especially outside of mild weather states on the west coast. And the total cost of ownership factor is key to communicate, but beyond the gas vs electricity costs – I think the maintenance costs differences is overplayed. The majority of EVs are leased today – meaning typically for 3 years. Very little goes wrong within 3 years of any new ICE or electric vehicle. Oil changes are basically the only difference in the first few years, so you are looking at $100-$150 more for an ICE, but that is probably about it. For older ICE vehicles, then the cost difference becomes significant.

On PHEVs, to me it is fundamentally about the transition for many people who are not yet comfortable going 100% electric – and a PHEV can give these buyers the best of the both worlds. Daily driving mostly in electric mode, and then for slightly longer trips and long road trips, they have the comfort of refueling as they currently do with their ICE vehicle. PHEVs could and should be the new hybrids.

Definitely a concern for those of us outside California, and not just as a matter of convenience. I hike in a fairly sparsely populated part of the country, and will regularly drive 2-4 hours to a trailhead. Where, needless to say, there’s no electricity. I recently made a four-hour drive (one way) to a trailhead where the biggest town I passed through the entire trip was <2000 people, and that was right near the beginning. Not another town over pop. 800 the rest of the way. And in a low-income rural area, this means no charging stations for 400 miles (round trip). My gas car was fine, and did the entire thing without a refill. Another multi-day trip I did required a substantial amount of driving on forest service roads between trailheads and a campground (with no services), where there will never be a chance to charge regardless of how ubiquitous BEVs become.

But even in town, my SO has a job that involves driving to clients' homes all over a large area. Can rack up hundreds of miles in a day. Can't just ask to plug in at a client's home, and can't wait around a half hour waiting for a charge when an assignment comes in.

I lived car free for a long time, and would use carshare when needed. It would be a good option for the occasional long trip to supplement a short-range car, but where I live now there is no carshare. Traditional car rental is a joke (huge hassle, blindsiding fees, crappy car selection, and they often substitute cars on you. No way could I trust their vehicles to get me to a trailhead the way my Subaru can.)

Very much looking forward to longer-range EVs.

Charon, your use cases are obviously in the minority – but speak to why for some percentage of the population (especially in the US with so much rural country), the EVs with less than 400 miles of range just aren’t going to cut it for many people. I wrote an article last year arguing that 500 miles would be required for late adopters in the US – https://evadoption.com/500-miles-of-range-one-key-to-late-adopters-embracing-evs/ – and yes, rental and subscription services, etc are not yet the solution to solve for the longer trips. A second ICE car for many, or a PHEV are more realistic options in the near term.

The bifurcation of electrifying our personal transportation results in virtually no cars with plugs in most of the USA. Pure BEVs with ridiculously expensive fast charging are fighting the near-perfect PHEVs that have no range anxiety and work better with low cost “slow” charging. PHEVs clearly should be winning. But, the manufacturers don’t want us buying PHEVs as they simply can’t make money on them. Instead, they pretend to be behind BEVs that they know won’t sell beyond 2% of the market. Follow the money. The money is in ICE CUVs and SUVs and Pickup Trucks. The fight between BEVs (and expensive charging) and PHEVs is splitting our tiny market. Meanwhile, ICE is crushing us everywhere but in a few parts of the country where BEVs can win because owners are willing to compromise for the downsides.

Interesting view Park to Spark. I’m a big fan of PHEVs and agree they could and perhaps should be the key focus during the long transition to pure BEVs. They solve range anxiety, and ones with at least 40-50 miles of range can meet probably 90% of most household’s needs. And as you say, L2 charging is all you need. I haven’t seen profit numbers on PHEVs vs. BEVs – I need to research this – but I thought it was in fact the opposite. No automaker is making a profit on BEVs (rumor is that Nissan has on the LEAF, but hasn’t been confirmed) – but that perhaps some of the PHEVs were profitable. The biggest issue to me as I point out in the article, is that there are only 3 PHEVs with 30 miles or more of range. To really be the killer EVs, I think PHEVs need at least 40, if not 50 mile of range. But so many have less than 20 miles, which is just unacceptable.

Thanks Loren. Love your work. The PHEV “lose money” is a direct comment from the dealer that sold us our Honda Clarity PHEV here in the Pittsburgh area. Two dealers were happy to sell us the car for $3,490 under sticker (9%). I realize that is not proof of “loss”. But, it isn’t a good sign of profitability. I further assume that the Volt (which we own our second of those) is also a huge loser-or, it would not have been cancelled. We agree that the PHEV range of 40+ miles is key. Our Clarity and Volt meet our needs perfectly and are no-compromise solutions-even here in the suburbs in the Land of Pickup Trucks. Workplace L1 or L2 charging (another key to growth of adoption) helps us drive 80% electric-even though it would be cheaper to just drive home from work on gas than to pay $3+ to fill up on juice.

Thanks for the kind words. Ya, this Electrek article https://electrek.co/2019/02/08/gm-electric-car-profitable-next-decade/ – references that both the Chevrolet Bolt and Volt are likely unprofitable as GM’s CEO said their EVs aren’t likely to be profitable until early in the next decade. McKinsey says there is currently a $12,000 difference in cost between a typical BEV and ICE – https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/making-electric-vehicles-profitable

AlixPartners “pegs the cost of building new electric cars at almost $9,000 more than conventional cars, and plug-in hybrids at an additional $5,700.” – https://www.greencarreports.com/news/1119167_electric-cars-are-clean-but-can-they-be-profitable-new-report-casts-doubt

Getting electric vehicles to be profitable is the key issue to drive supply and then demand among consumers.

I totally agree on this post. It’s idiotic to me that manufacturers are still making ICE vehicles at all when PHEVs have no downsides. A lot of places don’t have the charging infrastructure yet, at home (apartments), destinations, or in-between, but putting PHEVs that get 40-50mpg on gas out in the wild will create more demand for electric charging and solve the chicken and egg problem. They also work well with L1 charging at home so that an electrician isn’t needed to install an L2 charger required by make a BEV practical.

The problem is that the current PHEV market is pretty limited, and many of the vehicles are severely compromised vehicles, whether with cargo space, gasoline range, or elsewhere. While PHEVs don’t have all of the maintenance advantages of a BEV, they should have most of the advantage. If they are smart with regen braking, they shouldn’t ever need new brakes, and they should only need an oil change every 6 months, since the engine just doesn’t run that much, and even after the electric range, they aren’t running full-time in a mix of city and highway driving, where city driving spends a lot of time in all-electric mode. I’d like to see more true pure-electric-drivetrain PHEVs that use a generator as opposed to the parallel hybrid model. This allows for a much smaller engine and more efficient drivetrain that can still drive as a hybrid for unlimited range on gasoline. The batteries average out the load, and you can drive a decent sized car or small SUV on a sub-100HP engine and still have 200HP+ for acceleration and hill climbing.

I’m also interested to see where the technology goes for fuel cells. Currently, the only fuel cells that work in cars are hydrogen-powered, which makes the EV infrastructure look great by comparison. However, companies are developing fuel cells that can run on diesel or Jet A-1 for commercial sleeper truck and aircraft hotel power. It shouldn’t be too much of an extension to get them to run on gasoline if the cost can be kept in check. A gasoline-fuel cell PHEV would allow for a less compromised design with a larger battery pack, but it would still be able to run off of gasoline, and likely get upwards of 100mpg on regular gasoline or diesel fuel.

It is late at night so only a few words… Perhaps some education is needed but there are some substantial advantages to renting a car for the long trips, particularly for a family. During a trip in one’s personal car any breakdown can be devastating to a vacation or family visit. If the vehicle is a rental, the trip continues with a replacement and someone else deals with the problem. Furthermore, the choice of vehicles can match the family trip needs, rather than being a compromise with the daily needs.

I came across this post and wanted to leave a thought. Twice a year I get in my Suburban with wife, dog, cat and stuff and travel either to my winter or summer home. 1350 miles one way, usually 900 miles the first day. This trip will include a 6×12 trailer going north. Seems to me with the battery life on EV’s being what it is, and charging stations being sprinkled here and there, that there’s always going to be a place for a vehicle with a fossil fuel burning engine. That goes for long haul trucking, rail (run on DC electricity generated by high torque diesel engines), Air travel (kerosene), and even electrical generation itself.

I think EV’s will take on a larger transportation role, and I’m all for it. But enthusiasm is not a substitute for intelligence. Alex (above) has enthusiasm. But if you choose a commercial vehicle, van, utility truck, bus, train, motorcycle, moped, or military vehicle (there are more) you’re out of luck.

Viewed at from a position of privilege, yes, an EV will not currently suffice for 2 or 3 long distance vacations a year, cross-country road trips, and sporting events in remote locations. But they’ll be fine for the typical American family that gets 1 vacation a year, has most relatives living within 25 miles of where they were born, and sporting events consist of soccer and football matches at the local high school.

People can and should buy vehicles that suit their day-to-day needs, not the extreme edge cases cited by the author. When my mail-order business shipped out 200 packages a day, I needed a cargo van to make the daily post office run. Now I don’t.

It’s the same reason I don’t buy myself an 800 hp Dodge Demon. Although 0-60 in 2.3 seconds and a top speed of 211 MPH sounds nice in theory, my local roads and sheriff’s department don’t support that kind of driving.

This is why I am a big fan of PHEVs – they will meet the needs of a lot of people who just are not ready for a BEV.