As sales of electric vehicles begin to reach significant numbers across the US, states are exploring approaches to replace lost tax revenue since EV drivers don’t pay fuel taxes as drivers of gas-powered cars do at gas stations.

Unfortunately there is currently no simple and agreed upon best replacement for the fuel tax. The current approach of the fuel tax is simple, fair, and the collection and payment infrastructure is in place. Drivers of gasoline- and diesel-powered cars and trucks pay a fuel tax when filling up a a gas station/convenience store and then the gas station owners send payment to the tax authorities in their state.

If you drive more — and hence benefit more from public roads and infrastructure while also having greater impact on them — you pay more. And if the vehicle you drive is less efficient, you end up paying more because your vehicle consumes more fuel.

The only unfairness, or inequity, in this model is that moderate and lower-income households will pay a greater share of their income on fuel and fuel taxes. This is due to modest-income drivers tending to drive used, and older less-efficient cars and trucks, and also frequently having longer commutes than higher-income households. But putting this greater impact on lower income households aside, and which the design of a fuel tax likely cannot resolve, the current fuel tax model is brilliant in its simplicity and general fairness.

Declining Fuel-Tax Revenues: Beyond Electric Vehicles

While many politicians and the anti-EV crowd conveniently point a finger at EVs for the coming decline in fuel-tax revenue, electric vehicles are just one of several trends that are contributing to a decline in fuel tax revenue. These include:

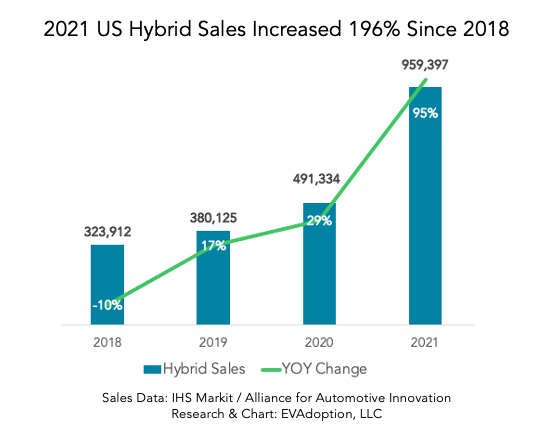

- The growth in sales of regular hybrids. In 2021, hybrid vehicles accounted for 6.9% of new vehicle sales in the US, versus 1.9% in 2018. This is an increase in five percentage points in four years, or 263 percent. Hybrid sales also increased 95% in 2021 and 196% since 2018. Since many regular hybrids obtain a 50% increase in MPG, if hybrid sales continue to have their sales resurgence, they will contribute to a significant reduction in gas tax revenues.

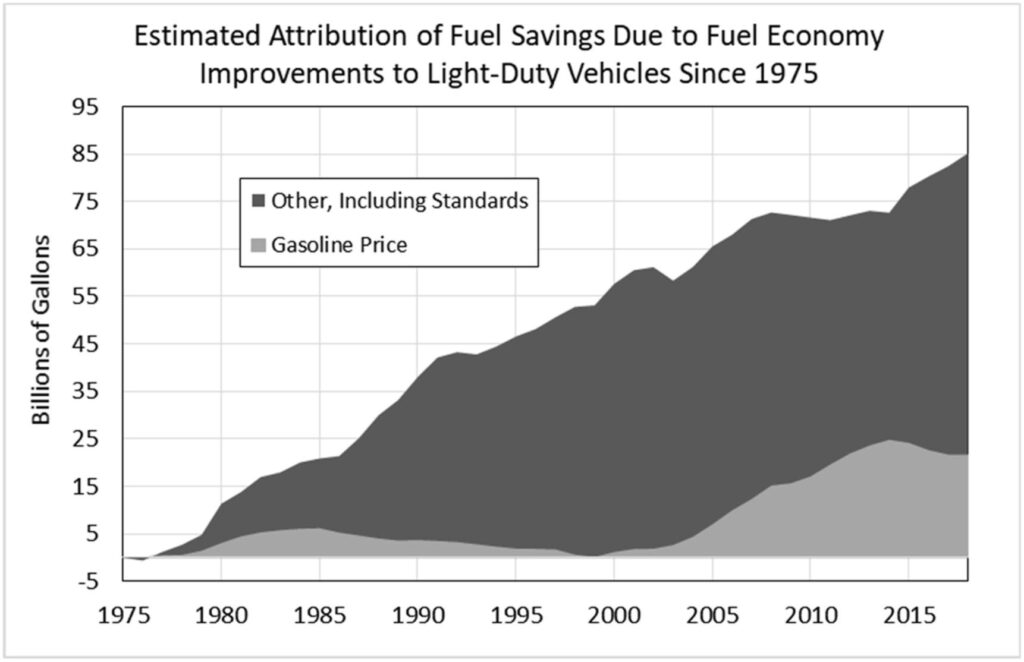

- In the 20 year period of 1997-2017, the average miles per gallon (MPG) of new passenger cars increased to 39.4 MPG from 28.7. This is an increase of 10.7 miles or 37 percent. And light trucks saw MPG increase 8 miles (38.8%) to 28.6 from 20.6 during the same period. And according to a new study, the improvement in light-duty vehicle fuel economy saved approximately two trillion gallons of gasoline from 1975 to 2018.

- Not so coincidentally, the US government’s Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, had almost the exact same increases during this period.

- Earlier this year, new CAFE standards require an industry-wide fleet average of approximately 49 mpg for passenger cars and light trucks in model year 2026. The new standards will increase the estimated fleet-wide average by nearly 10 miles per gallon for model year 2026, relative to model year 2021.

- Work from home, the rise of ecommerce, and higher gas prices for an extended period could also reduce average annual vehicle miles traveled in the US. A recent McKinsey survey suggests that as many as 92 million Americans are able to work from home at least part time. Doing a simple calculation, if these workers commuted an average of one fewer days per week with an average of a 30 mile commute, roughly 13% fewer miles would be driven annually. A counter trend, however could be more households going on road trips if airline prices remain high for an extended period of time.

It is also important to understand electric vehicle’s actual percentage of total vehicles in operation. As of today, less than 1% of vehicles on the road in the US are either BEVs or PHEVs. And by our EVAdoption forecast, if new BEV sales reach 44% in 2030, the percent of EVs in operation would reach approximately 11 percent.

When 1 out of 10 vehicles on the road in America don’t use any gasoline, then that will have a real impact on fuel tax revenue. But at least for the next few years, other trends such as the growth in hybrids and better fuel efficiency combined with potentially millions working from home part of the time and people driving less — may have a bigger impact on declining fuel tax revenue.

Other Considerations

First, electric vehicles clearly need to pay their share for building roads and infrastructure and maintenance. Anyone who makes an argument otherwise because BEVs don’t emit tailpipe emissions is simply wrong. If you drive a vehicle on US roads — regardless of powertrain — you need to pay your share to keep them maintained. Period.

However, just blaming and focusing on electric vehicles ignores the other trends of gas-powered vehicles getting more efficient each year and the potential for reduced average annual vehicle miles traveled due to remote working and other trends. To address those issues, states must consider adjusting the existing fuel tax rate to account for greater efficiency and fewer miles traveled.

A second consideration is weight. There continues to be a shift towards consumers buying trucks and large SUVs and now combined with electric vehicles having large and heavy batteries. Increased vehicle weight has a greater impact on the wear of roads and therefore annual registration fees may need to be adjusted up to reflect the growing population of heavier vehicles.

Alternatives And Supplements to the Existing Fuel Tax

So what’s the best, fairest, and likely least objectionable approach to taxing electric vehicle owners? There are multiple proposals that states and the federal government are exploring and testing, but almost all of them bring challenges or concerns about collection, privacy, and fairness that are usually not leveled at the existing fuel tax approach.

Some (but not all) of the fuel tax approaches that have been proposed include:

Tire Tax: This approach adds an additional tax on the purchase of tires. The main problems with a tire tax of course is that tears wear at different rates, car owners would pay the tax at very different intervals, and it would also encourage people to put off replacing tires which would reduce safety.

General Sales Tax: Currently, five states do not have a sales tax so this approach wouldn’t work in those states. And secondly, whatever formula that is devised would overtax those consumers who don’t drive (although they still benefit from roads and infrastructure) and undertax those that drive much more than the average driver. This is simply not an equitable approach and won’t work in states without sales tax.

Car-Only Sales Tax: An additional tax on new and used car sales would put a one-time increased financial burden on moderate and low-income drivers. And since people may hold onto a car or truck for a few years or 15 years, such a tax would not be equitable.

The only way it would work is if the tax was levied every year akin to property tax and perhaps paid along with annual vehicle registration fees. This of course again puts a one-time per year financial burden on car owners as opposed to the “pay-as-you-use” approach of the current fuel tax.

Annual Tax on Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT): One of the most popular proposals is to enact a tax based on the number of miles a vehicle travels annually. The beauty of this approach is that it is fair from the perspective of the more you drive and benefit from (and impact) roads and infrastructure, the more you pay.

The challenge is of course around how to track the miles all vehicles travel each year? Vehicles could be issued transponders akin to toll-taking transponders, but this raises privacy concerns among many who don’t like the idea of the government knowing their whereabouts. Some states have annual inspection requirements where the vehicle’s mileage could be recorded and a fee paid. But many states do not have these annual inspections and this approach again creates an additional annual (one time p\er year) financial burden on moderate/low-income households. And this method could lead to drivers of all income levels taking various cheating approaches to lower the miles shown on their odometer. There are likely too many issues with a VMT approach to see it win out.

Registration Fees: In addition to existing vehicle registration fees, an annual road and infrastructure fee would be added. This again, could be similar to a property tax and existing registration fee approach with the fee based on the cost and weight of the vehicle, or other factors. But this approach lacks fairness since there someone driving 1,500 miles would pay the same as someone driving 15,000 miles. And again, unless the fee was paid to state taxing authorities on a monthly basis, it increases the annual fee burden on drivers versus the pay-as-you-go model.

And one of the downsides of any of the above approaches that are collected on an annual basis is the lengthy delay in payment to a state from the time that a driver actually benefits from roads and infrastructure.

Since a fuel tax is pre-paid, if we go to a mileage tax, there will be a major shortfall of funds in all jurisdictions. Why? Because a mileage tax would be post-paid. But with a mileage tax, drivers would have to wait for a billing statement which might come monthly, quarterly, or annually potentially leading to collections challenges and revenue shortfalls. — Anonymous Employee of a State Department of Motor Vehicles

Electricity/kWh EV Charging Tax: Arguably the best supplement to, and replacement of, the existing tax per gallon of gas and diesel purchased is in essence an identical tax on the “electric fuel” that vehicles powered by batteries and stored electricity consume. (I dive into why and the challenges in the section below.)

Tax on Electricity (kWh) Consumed By Electric Vehicles?

The beauty of the existing fuel tax model is its simplicity. The more you drive and hence the more fuel you consume as a vehicle owner, the more tax you pay. With gas- and diesel-powered vehicles, you “pay at the pump” at gas stations, convenience stores, and increasingly large retailers like CostCo, Sam’s Club, and Safeway. In most cases these retailers pay the collected tax monthly to states based on the previous month’s fuel sales.

Fair. Simple. It works.

So why not try to replicate that same model, but just apply the tax and model to the different fuel of electricity?

Electricity is sold by a volume metric using kilowatt hour (kWh) just as gasoline is sold by the volume metric of a gallon (in the US, liter of course most everywhere else in the world.) And EV drivers refuel at charging stations whose owners or operators can also pay a collected kWh tax on a monthly basis.

Sounds simple, logical, and easy doesn’t it? Except it isn’t that simple. Here’s why.

Public Charging

As mentioned above, with EV drivers charging at public charging locations, a “fuel” tax that is based on kWh delivered to the EV is very similar to a per gallon tax at the gas pump operated by gas stations. Charging station operators can add a per kWh tax which is then paid to the states in the same manner that gas stations currently pay the fuel tax.

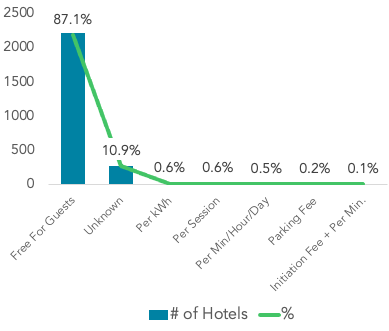

One challenge to this approach, however, is that tens of thousands of sites such as hotels, resorts, and restaurants offer free charging (no payment or account) and deploy “dumb chargers” that are not connected to cellular or Wi-Fi. In fact, perhaps as many as 50% of the Level 2 chargers (Tesla Destination Charging, Non-networked, among others) in the US are either free to charge and/or are not connected to the internet or network to track usage or collect payment. And analysis of data from the Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC) earlier this year suggests that nearly 90% of chargers deployed at hotels, for example, are free to use.

These chargers would have to either upgrade the charging hardware and software or add on a card reader or other method that enabled the ability to collect a tax and payment. One of these options is adding a near field communications (NFC) capability to these chargers in combination with the driver then paying via a mobile app on their smartphone. For this to make sense, existing chargers would likely be grandfathered with all new deployed chargers being required to add the ability to accept payment of tax or at least reporting of kWh consumed to the site host. Another approach for these “dumb” chargers would have to be some type of estimated tax.

This could obviously have an impact on the appetite for hotels, restaurants, national parks, employers, et al to provide charging as a free amenity. And requiring host sites to start collecting sales tax will not likely go over well.

For the public charging networks, especially the major DC fast charging networks like Electrify America, EVgo, and Tesla Supercharger, collecting a tax based on a per kWh rate would not be difficult. It would require an upgrade to their software and then paying each state on a monthly basis the same as gas station operators.

Most EV Charging Is Done Where People Live

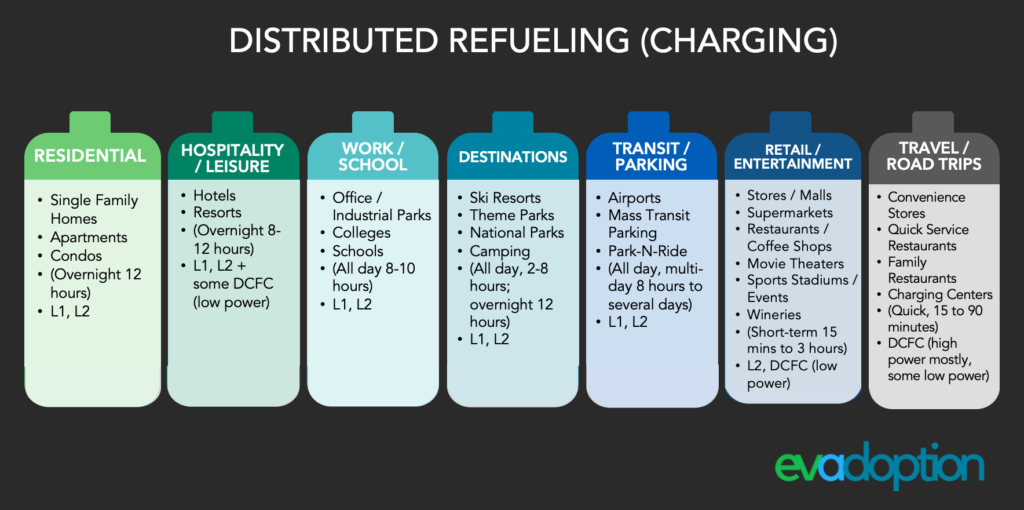

But a huge difference between refueling gas versus electric cars, is the centralized versus decentralized approach. Except for fleet operators, nearly 100% of refueling gas cars is done a a centralized gasoline retailer. But refueling an EV is done whenever and wherever the car is parked in a mostly decentralized manner.

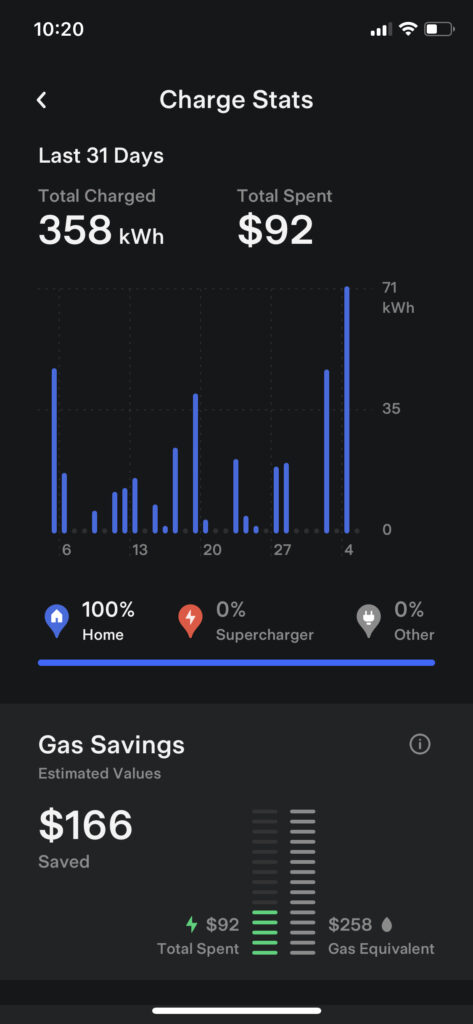

And for most EV drivers, the vast majority (often 80%-95%) of charging is done where they live. In essence the home or apartment is the new fueling station location. And from a kWh tax collecting perspective, this would most likely have to be assessed and collected via a driver’s electric utility, which would then pay the state each month.

Since utilities already bill their customers and charge taxes on a monthly basis, this would not be that difficult to implement. The only wrinkle would be deciphering the difference between electricity used to charge an EV versus all other uses of electricity. But this could be done through a meter on the EV charging hardware, utility smart meters, telematics and the car’s mobile app, or third-party companies such as WeaveGrid that already capture data and sit between the EV, OEM, EV owner, and their utility.

The Tesla mobile app, for example, tracks the amount of kWh from charging and by source/location – home, Tesla chargers, and other. Most OEMs have mobile apps for their EVs and it would be easy enough to add this and reporting and payment functionality. The data and payments could be sent to the OEM who then pays each state, to a third party, or potentially directly to a state. In this case, Tesla also knows the location of the charging station where I charged when away from home, so this data and payment could then also be sent to other states beyond where you live.

If an EV driver lives in an apartment or condo (without installed chargers) or downtown urban location without a garage or street charging access — then they have to rely on public charging — which can be collected per the approach outlined earlier. If their apartment does have chargers installed, the tax collection method could follow either the homeowner or public charging station model.

Some EV drivers also charge during the day from solar panels on the roof of their home (I have solar but charge my EV overnight during PG&E TOU rates). In this case, again, an approach using vehicle telematics could report the kWh charged into the EV or a mobile app that controls charging and solar like the Tesla app. The app could have a reporting and tax collection aspect paid through a debit or credit card.

Fairness

No solution and alternative or replacement to the existing fuel tax method will make everybody happy — and all approaches have weaknesses and issues. But rather than thinking in terms of replacing the existing fuel tax method, let’s keep it in place s long as there are gas- and diesel-powered cars on the road and gas retailers to refuel them. It works and is fair and equitable.

And then what is needed is a new tax that works in much the same way as the existing fuel tax, except that the fuel being taxed is electricity. Putting aside some of the potential collection challenges, a kWh tax is probably the best and fairest method of generating tax revenue from EVs to maintain and build our roads and infrastructure.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments.

2 Responses

Fairness? In Taxes? From the Government? You are kidding, right? In the state of WA my understanding is that the state taxes electricity at approximately the same rate that it taxes gasoline – when I checked a while back, both were around 14%. Now, why not just allocate that tax to the road? In WA they charge an additional $75/yr for a hybrid and $225/yr for an all electric on your registration. BUT, that also applies to motorcycles! I have to pay an extra $225/yr for my electric motorcycle! A motorcycle that only holds a 40-50 mile charge will never use enough “fuel” to ever justify that exorbitant cost! Motorcycles are the highest polluters for their size of any ICE engines, so the state is penalizing severely anyone that wants to drive an electric motorcycle. I always get the feeling that they are continually looking for an excuse to tax us MORE and this feels like more of the same. For the most part I have not been impressed with the spending of the revenue for roads. The glut of social give-away programs (the recent Covid handouts and unemployment being a good example) cause the government to take from infrastructure and other necessities to supply them. This, in turn causes ever-increasing inflation, which makes it more and more difficult for the common man to make a living, especially for a family. I’m not a tax protester or sovereign nation proponent, but I am also not inclined to “volunteer” ways where I “feel good” about additional ways and amounts of confiscation.

Bill, you raise relevant points – but my article intentionally did not address any issues around how fuel taxes are dispersed and if they should even be collected. The fundamental issue is states are grappling with ways to replace or supplement the existing fuel tax on gas/diesel. An entirely new approach might make more sense, but I’m dubious that would happen in America.