Like many issues and discussion topics today, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) have become a divisive concept within the electric vehicle industry.

People seem to either be fans of the dual-powertrain approach of PHEVs or have a huge disdain for them. Black and white. Good versus bad. There seem to be a few people in the middle.

But like most things in life, objective analysis shows that PHEVs are neither black or white or good or bad. But rather, depending on the PHEV‘s driver habits and the PHEV itself, they can actually be really good in helping reduce tailpipe emissions or slightly worse than say a regular Prius hybrid.

Many industry observers (myself included) believe that PHEVs with 30 to 40 miles (or more) of electric range (sometimes referred to as “strong hybrids”) and which are plugged in and charged on a daily or regular basis are a great solution for many households. This includes those households with consistent daily trips — whether to work, school, or errands — that can be driven completely or mostly in electric mode, and who then also frequently take long-distance trips where they can rely on the gas engine.

The Knocks Against PHEVs

There are four main arguments against PHEVs:

1. Not enough range: Many plug-in hybrids have minimal electric range of around 20 or less miles. This is in fact true, but this can be mostly rectified via a simple change in how PHEV incentives are structured. And categorizing all PHEVs as bad because several have a rather paltry amount of electric range unfairly diminishes the value of those with adequate range.

2. Drivers not plugging in: Some percentage of drivers (we don’t have solid data on this in the US) frequently or never plug-in their PHEV, which in essence turns the vehicle into a heavier and less-efficient regular hybrid. This of course is not a good thing as this practice wastes the benefit of the battery in the PHEV and simply adds weight and complexity. And perhaps most annoying, it wastes our precious taxpayer dollars that should be going to EV owners who do plug in.

But again, our approaches to incentives can help address this behavior. Current federal and state incentives reduce the effective cost of a PHEV and some states may reward drivers with HOV lane access — but do not have any method built in to hold drivers accountable for actually plugging in their vehicles.

3. PHEVs use gasoline: PHEVs still have a gas engine which is “bad and evil” as they run on fossil fuels. This is a very myopic view and doesn’t account for actual human behavior and that our target goal is to reduce GHGs 50 percent by 2030, not switch to only BEVs overnight — which is impossible. The transition to 99% (I say 99% as there will always antique and collector ICE cars in operation) zero tailpipe emission vehicles in operation is going to take until at least 2050. Reducing GHGs as quickly as possible is the goal, and a BEV-only strategy will actually slow our chance to reduce emissions.

4. PHEVs are not the future: The other knock against PHEVs from the BEV purists is that plug-in hybrids are an outdated technology and form of powertrain. They require two separate powertrains, are heavier, still use gas and require maintenance like oil changes. And that is all true, but we can’t let the idea of what some people think is the ultimate perfect solution (BEVs) cloud the reality of human acceptance of new technologies.

“Perfection is the enemy of progress.”

— Winston Churchill

While pure electric (BEV) powertrains are clearly the future of personal transportation vehicles, in the near term PHEVs are actually the ideal solution for many people. PHEVs also serve as “training pants” or “gateway drugs” for people who aren’t quite ready to go BEV or that may not fit their driving situation and needs. PHEV haters need to look beyond what works for them and the ideal technology, and understand the bigger goal we are after.

The Goals Of New PHEV Incentives

In my view, there are three behaviors related to PHEVs that need addressing, and they can mostly be addressed through the proper design of incentives. They are:

- Automakers producing PHEVs with less than 30 miles of range.

- Consumers buying or leasing PHEVs with less than 30 miles of range.

- Some owners of PHEVs not plugging them in regularly and not driving mostly in EV mode.

New/Revised EV Incentives

Following are suggested approaches to addressing the above three issues with PHEVs.

Minimum EPA EV Range of 30 Miles: The current federal EV tax credit does not have a minimum EPA EV battery range, but rather has a 5 kWh minimum battery size requirement for an electric vehicle to qualify for the tax credit. Instead, the tax credit should have a minimum range requirement of 30 EPA miles. California already made this change to its rebate program in 2021 — all other states, utilities, and the federal EV tax credit should follow suit.

Eligible PHEVs must have a minimum all electric range of 30 miles in compliance with the EPA test standards (45 miles UDDS).

— California Clean Vehicle Rebate program

PHEVs with less than 30 miles of range would be less attractive to consumers, many of whom buy or lease these shorter-range PHEVs primarily because of the federal tax credit, combined with state and utility incentives and HOV-lane access where available. And if consumers dramatically cut back on purchasing these PHEVs, the automakers would lose money for from very low volume or be forced to either discontinue them or increase the battery size and efficiency to reach 30 miles of range.

The federal EV tax credit needs be designed to treat PHEVs very differently from BEVs, but the current and proposed changes apply the same battery-size requirements across both types of EVs, which makes zero sense. While adding more complexity, all PHEVs with 30 miles or more of range (and under an MSRP cap of say $50,000) might have a base tax credit or rebate of $5,000 and then qualify for an additional $125 per EPA mile of range up to 50 miles and a maximum of 50 EPA miles.

Tax Credit or Rebate Based on Percentage of Electric Miles Driven: To address the issue of some PHEV owners rarely or never plugging in, any government incentives should be based on the percentage of miles driven in EV mode. This approach would penalize PHEV drivers who rarely or never plugged in, and reward those who drive mostly in EV mode.

Using behavioral economist John A. List’s “clawback” approach outlined in his book “The Voltage Effect,” we might start with one-fourth of the maximum federal EV rebate being provided to a PHEV buyer at time of purchase. This upfront amount is using to provide an immediate benefit to the PHEV buyer, but then adding EV mode mileage requirements that puts that money at risk.

But then at the end of each of the next three years, the amount of rebate would be determined and “trued up” based on the percentage of miles driven in EV mode. PHEV buyers might calculate that over the 3 years they would receive say $5,000 and in their head bank on it is being “almost guaranteed.”

So using $7,500 as the maximum rebate amount, a PHEV buyer would be incentivized at the time of purchase with an $1,875 rebate. But then at the end of the year their rebate amount would be based on the percentage of total miles driven in EV mode. For example, if the PHEV owner drove 12,000 miles in total and 9,000 in electric mode, that year’s refund would be $1,406 (9,000/12,000 = 75% X $1,875).

The core idea of this approach is to leverage the behavioral economics concept of “loss aversion” where people are motivated more by the fear of losing something of value, than a potential gain. But additionally, through multiple field tests by the economist List and his team, he discovered that giving people an upfront incentive combined with needing to hit certain goals or risk losing financial gain produced the best desired result.

So in my example, if a PHEV driver assumes that each year they stand to benefit from up to $1,875 per year, they will be motivated to drive as much as possible or risk losing what has in essence been guaranteed for them.

Now the hard part. How to actually track how many miles a PHEV owner drives in total and in electric mode each year? As part of the benefit of receiving the rebate from the government, the PHEV driver would have to agree (opt-in) to the automaker’s vehicle telematics data sharing. Once per year the automaker would provide the data on each PHEV — total miles and miles driven in electric mode — to the government body that dispenses the rebates. Does this raise fears of privacy and government invasion and tracking? Sure, but if a consumer receives several thousands of dollars in taxpayer money designed for electric vehicles, then should agree to actually being held accountable for receiving those funds.

Is this all a lot of trouble and effort just to increase how often PHEVs are plugged in and ensure that our government dollars are being spent responsibly? Perhaps it is, but PHEVs will continue to play an important role in reducing GHGs from personal transportation in the years ahead.

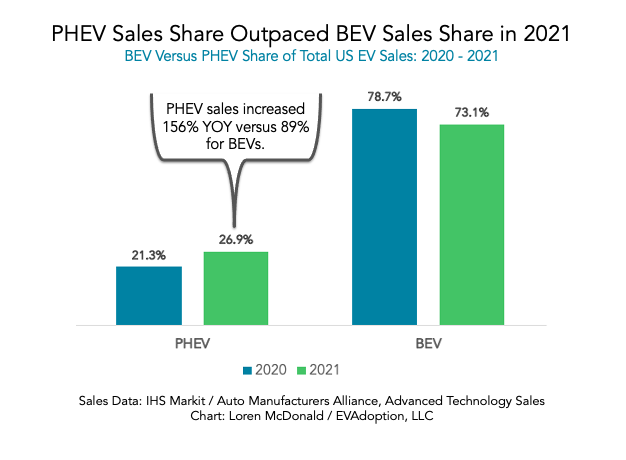

In fact, in 2021 PHEVs actually increased their share of EV sales in the US versus BEVs and YOY sales increased 156% versus 89% for BEVs, which of course had a much larger base. But for PHEVs to actually be effective in the goal of reducing GHGs, we can no longer incentivize automakers to produce low-range EVs and for consumers to buy them and rarely or never plug them in.

Let me know in the comments what you think and especially if you have a better or simpler approach to holding PHEV drivers accountable for plugging in their vehicle.

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

Announcing the acquisition of EVAdoption by Paren →

6 Responses

I was 100% in agreement with you until you got to tracking mileage. The less invasive and better approach would be to make driving on gasoline more expensive for all, driving both PHEV drivers to minimize it and all drivers to switch from ICE.

My tax proposal is that we raise the federal gas tax by $1/gal or more, while providing a flat refundable tax credit of $500 per adult and $250 per child. This increases the marginal cost of using gasoline, while being cost-neutral for someone using 500 gal/year of gasoline, which should cover the median use in the US. And as a flat credit, those using less receive an incentive to use for other transportation. In truth, the tax increase should probably be $2-3/gal to match externalities.

Half Integer, I don’t disagree with you on y idea of tracking mileage – as it is both complex and raises privacy concerns among many. But if it can be figured out, it is also the fairest approach and may be the direction we are headed for replacing the fuel tax anyway. States are testing different approaches to collecting a replacement for the fuel tax – and the only true fair approach is based on the actual miles people drive (plus potentially the weight of the vehicle as heavier vehicles cause more road damage).

That aside, I like your approach from a simplicity perspective, but I don’t like any approach that raises the cost of fuel for people who are at the middle and lower-income levels – which your approach does. Someone who makes $40,000 per year and has a daily commute of 100 miles in their 10+ year old vehicle getting 15 miles per gallon has a huge burden placed on them versus someone making $200,000 year and drives 30 miles per day in a new hybrid getting 40 MPG. The refundable tax credit is fine, except the lower-income person spending significantly more money in January – meaning less money for food and rent – may not receive that credit amount for another 18 months (or more based on how slow the IRS is processing tax refunds currently). And that is simply too much of a burden. 38% of US households earn less than 50% annually, and 66.5% earn less than $100,000 per year. These are the households who mostly by older, less-efficient used vehicles and who simply don’t have the means afford EVs and more fuel-efficient vehicles and are also most likely to have longer commutes with fewer or no options for using public transit.

Raising the cost of gasoline only creates more of a divide in this country and unduly penalizes those with less income and fewer options.

Main problems with PHEV is that most of PHEV’s are ICE with EM addon where it should be vice versa. In order to drive normally EM is not enough and ICE have to kick in. Incentives must regulate power ratio between ICE and EM to be at least 1:1. Also proper EV mode must be mandatory.

Good overview, Lorn. However, good data supplied from both automakers and also government agencies do exist with regard to PHEV ownership behavior. If you reach out to Ford they can provide you with ownership behavior data on the company’s PHEVs, and data on the Volt has been available for the better part of a decade. Volvo will also offer you data on its new PHEVs and the percentage they are plugged in by owners. PHEVs are more pleasant to operate in EV mode. Any owner knows that is a big incentive to develop a plug-in habit. I value your opinions on incentives. Mine is that we should eliminate green vehicle incentives and see which vehicles the public prefers. Democracy and all that jazz. Moving back to the true definition of HOV would also eliminate anyone buying any specific vehicle just to gain access to that special lane. As to your range concerns, nearly every new PHEV has a 30-mile+ operating range in EV mode. The RAV4 Prime, the top seller in the U.S. last year, has 42+. Glad to see PHEVs getting coverage. The top-selling sub-$50K electrified crossover in America in 2021 was a PHEV, not a BEV.

Nice article Loren. Also in favor of PHEVs is reduction in battery costs/materials vs BEVs…I believe the ratio is 4 PHEVs to 1 BEV, all good for the environment etc. I recently moved from a Tesal Model YLR to a Volvo Xc60 Recharge T8 and I am getting 44 pure electric miles with a full charge. Most of my commute miles are within this range, so effectively I am driving a BEV. The Tesla is a nice car but we have experienced significant range anxiety on several long trips. I applaud Volvo’s aim to be 100% electric by 2030.

Thanks Kyle! And congrats on your ability to drive such a high percentage of your time in EV mode. As far as the ratio of PHEVs versus BEVs from the same amount of battery kWh – I used my data of the current median BEV battery of 84 kWh versus 14 kWh for PHEVs. If you did a sales-weighted analysis (e.g., with Tesla Models 3 and Y dominating US BEV sales, it would be somewhere between 4 to 5 to 1.